In many ways, Bernie Sanders is the anti-Trump. And, in important ways, he ran his campaign as the anti-Biden.

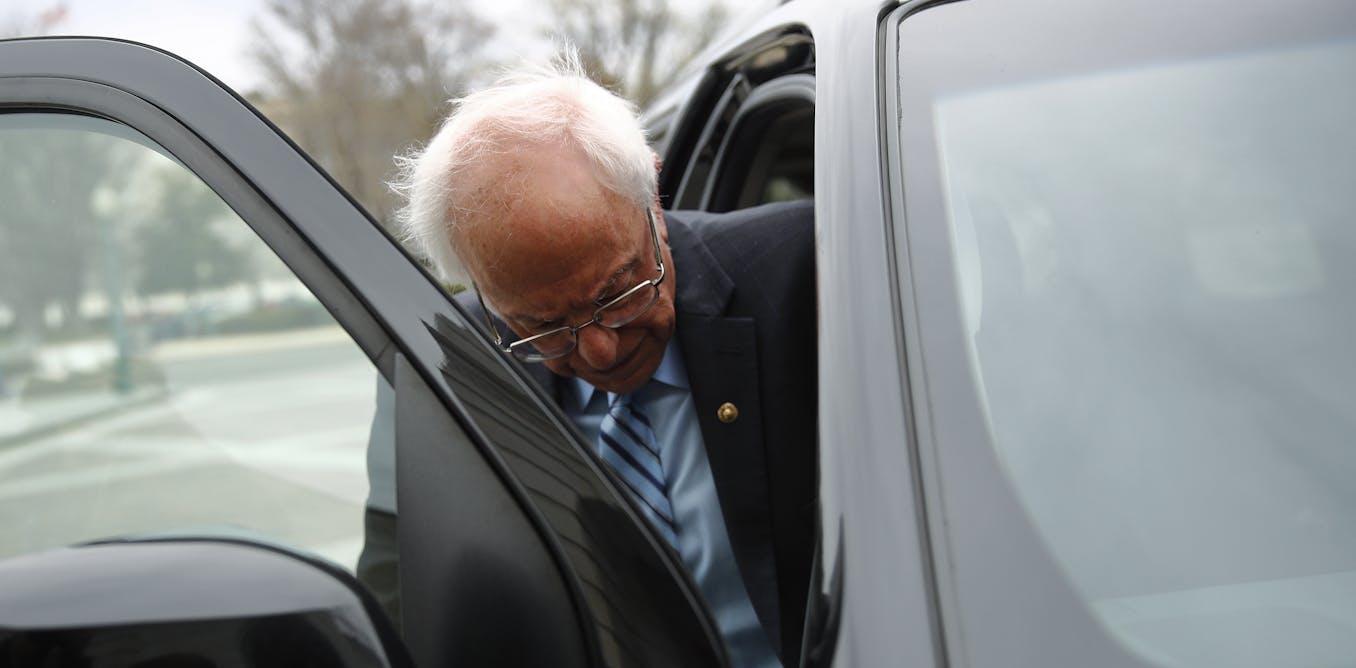

Sanders bowed out of the Democratic nomination race on April 8, repeating his runner-up status from four years earlier. His two runs at the White House have cemented his legacy as a consistent standard-bearer for progressive policies.

The veteran democratic socialist possessed a rare quality for a political candidate in this age of Trumpian fickleness. He is a politician whose actions and beliefs have remained steadfast over time and across campaigns.

But in the current political moment, it appears the Democratic electorate longs less for a politician who is consistent from day to day than one who can provide pragmatic leadership to unseat the vacillating Trump.

Same ol’ Sanders

Sanders ran his campaign as the antithesis of a political showman, who says one thing today and another tomorrow with little regard for facts and consistency. He has exhibited throughout his career what anthropologist Alessandro Duranti calls “existential coherence” – he is a political figure “whose past, present, and future actions, beliefs, and evaluations follow some clear basic principles, none of which contradicts another.”

As a linguistic anthropologist who studies language and politics, I know that traditionally, candidates have worried about how to project a consistent political persona, and they have often gone to great pains to do so. But Trump shattered that expectation, excelling in self-contradictions and inconsistencies – often within a single sitting.

Sanders, instead, has put forth a consistent vision that has remained more or less the same since his early days in politics as mayor of Burlington, Vermont. Rather than moving toward the electorate and shifting positions based on perceptions of what the electorate desired, the electorate has moved toward Sanders to join his vision for universal health care and other progressive causes. A CNBC survey in 2019 found that a majority of Americans supported progressive policies, including a higher minimum wage and Medicare for All – key issues that Sanders has been advocating throughout his decades-long political career.

In an episode of Comedy Central’s “The Daily Show” last year, host Trevor Noah unearthed footage from 1987 of Sanders discussing politics on a local public access channel in his hometown of Burlington. The Bernie Sanders of 1987 talked of the unfair tax system that placed a large burden on working people and the need for universal health care.

“We are one of two nations in the industrialized world that does not have a national health care system,” declared Sanders in 1987.

Three decades later, in both his 2016 and 2020 presidential campaigns, Sanders continued with that theme. In 2016, he released his Medicare for All plan by declaring, “It is time for our country to join every other major industrialized nation on Earth and guarantee health care to all citizens as a right, not a privilege.” His 2020 campaign website further echoed this sentiment, stating that “the United States will join every other major country on Earth and guarantee health care to all people as a right.”

A consistent candidate often comes across as a more authentic candidate – someone who is staying true to his core self rather than pandering to the latest polling data or saying whatever will attract the most dramatic news coverage. Sanders’ authenticity as a candidate who has fought for working people and progressive ideals his entire life made him appealing to many liberals. He attracted an unshakable following of core supporters because of it.

‘Results, not revolution’

Biden’s pragmatic approach, however, trumped Sanders’ often dogmatic consistency. In their debates, Sanders hammered Biden over what he saw as shifting stances on Social Security, Medicare and veterans’ programs. And then there was Biden’s 2003 vote for the Iraq war before he turned against it.

But this is not the 2004 presidential election, where accusations of flip-flopping can sink a candidate, like it did John Kerry in his race against George W. Bush. Perhaps Donald Trump’s fickleness has changed what voters look for in a candidate. Maybe it’s simply that nobody cares about Biden’s apparent lack of judgment in 2003, which occurred well before he spent eight years as vice president in arguably one of the most popular Democratic administrations in U.S. history.

Biden easily parried Sanders’ accusations of inconsistency by pointing to an underlying consistency of principles that have guided his varying positions over time. Voters ultimately decided to support someone who exhibits a practical sense of how to govern in a way that gets things done. As Biden said in his last debate with Sanders, “People are looking for results, not revolution.”

On health care, one might have expected Sanders to have an advantage with his Medicare for All proposal, a consistent theme across his time as mayor, congressman, senator and presidential candidate. Polling done by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that for the first time a majority of Americans began to support a single government plan for health care in 2016, corresponding to the Sanders campaign push for Medicare for All.

But in the same Kaiser poll, more Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents said they would prefer a candidate who would build on the Affordable Care Act rather than replace it. Biden’s campaign argued precisely for this more pragmatic approach, and he positioned himself as the right person to get the job done in a contentious political environment.

An overture

After sweeping the primaries in Florida, Illinois and Arizona in March – putting the wheels in motion for the eventual withdrawal of Sanders from the race – Biden then struck the right chord in his speech after the Florida primary by making an appeal to Sanders voters.

“I hear you,” he said. “I know what’s at stake. I know what we have to do. Our goal as a campaign and my goal as a candidate for president is to unify this party and then to unify the nation.”

Biden’s appeal to Sanders voters suggests he may be willing to absorb some of the best ideas from Sanders – and other candidates. It’s a pragmatic approach, rather than a dogmatic consistency, that may bring along their supporters, too.

That may be exactly what he will need to do to beat Trump in November.

[ You can read us daily by subscribing to The Conversation’s newsletter.]