Despite plans to go ahead with Brexit, the UK will now participate in elections to the European Parliament on May 23.

Voting in this election will take place across Europe between May 23 and May 26, with different countries holding votes on different days. The majority of member states vote on Sunday May 26.

Here is what you need to know about voting in the UK.

Voting in a region rather than a constituency

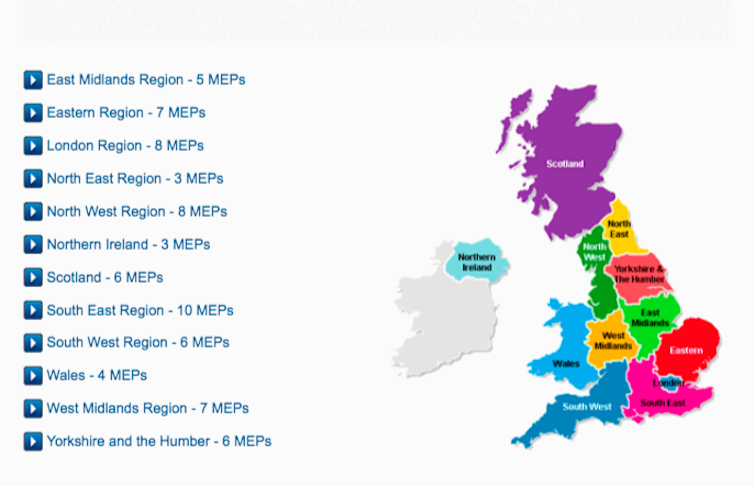

The way the country is carved up into voting areas is different to a general election. Rather than hundreds of constituencies, the UK is divided into 12 parts. Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland are represented as whole nations while England is divided up into nine regions.

European election voting areas. European Parliament

European election voting areas. European Parliament

Different regions and nations get different numbers of seats. In England, for example, the North-West gets eight and the South-East gets ten. Scotland gets six. Wales gets four. Northern Ireland gets three.

What’s on the ballot paper

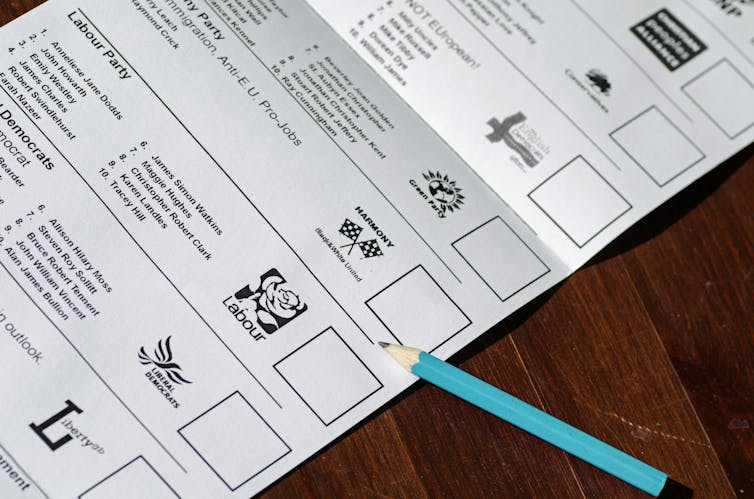

Since 1999, MEPs from the UK have been chosen using a closed list system (except in Northern Ireland). That means the ballot paper will show a list of parties in boxes. Within each party box there will be a list of candidates.

A 2014 ballot paper shows how candidates are listed. Shutterstock

A 2014 ballot paper shows how candidates are listed. Shutterstock

In a region which gets three MEPs, parties will usually list three candidates, if ten, ten candidates. They can’t list more but would be allowed to list fewer. Independent candidates are also listed on the ballot paper separately.

But voters don’t pick and choose between individual MEP candidates. They get one vote and use it to choose one party, or one independent, marking the box with an X.

How the counting works

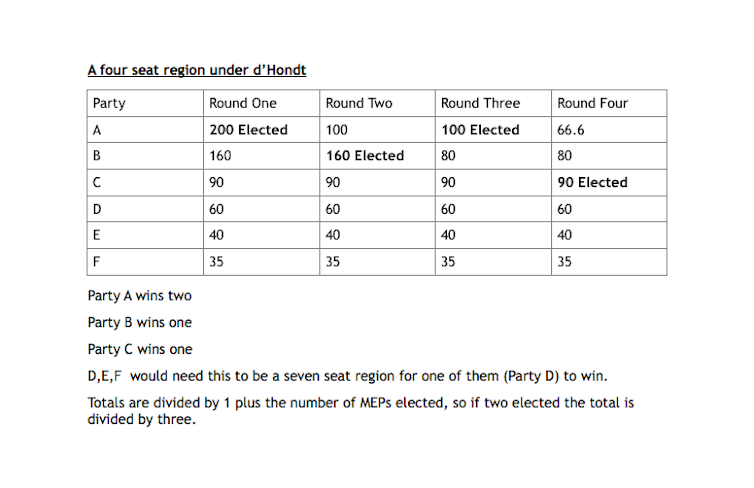

The way votes are counted in a European election is different to a general election too. A system called d’Hondt is used, which is meant to produce a broadly proportional allocation of seats.

The total number of votes for each party in each region are counted and then put in order. The party at the top gets seat number one. That is allocated to the candidate at the top of its list.

The winning party’s vote total is then halved and the whole list is looked at again. Whichever party is on top of this reordered list gets the next seat. That may well be the same party that won the first seat, if it has secured enough support, or it may be another party.

The party at the top of the second list (if it is a different party) then gets its vote total divided in half and the process is repeated. (If the same party has just won twice, the division is by three). This goes on until all the seats in the region are filled. Parties with less support may never reach the top and won’t win a seat. Chances vary depending on the size of the region.

How voting might work in a region electing four MEPs. Author provided

How voting might work in a region electing four MEPs. Author provided

In Northern Ireland, the election is carried out by single transferable vote, a system in which voters do have more than one choice. Citizens are used to this as it is the method for local elections and the Northern Ireland Assembly. They show their preferences by voting 1,2,3 and so on. In an STV system there is no real chance of a “wasted vote”.

Moving down the list

So, why is there a list of candidates if you only get to vote for a party? It’s because when each party chooses its representatives, it puts them in priority order. The candidate at the top of the list is the one the party most wants to get elected.

Candidates on the lower rungs of the ladder have no realistic chance of being elected – I say this as someone who has previously been number nine of ten.

But if an MEP resigns or dies during their term in parliament, their place is filled by the next person down the list (rather than in a by-election). This has actually happened. When Diana Wallis, Liberal Democrat MEP for Yorkshire and the Humber resigned in 2012, she was replaced by Rebecca Taylor. For these purposes, defecting out of a party does not count as a vacancy.

How Brexit changes the game

Voters may feel the ballot papers for this election are longer than usual. That’s because they are. They feature several new parties, such as Change UK and the Brexit Party, as well as some other less familiar ones, such as The Yorkshire Party.

We are also seeing the rise of so-called “celebrity candidates” such as Boris Johnson’s sister Rachel Johnson for Change UK and former Conservative minister Ann Widdecombe for the Brexit Party. But it’s worth remembering that these celebrity candidates are there to raise profile more than anything. Because the contest is between parties, no aspiring MEP can really call on a “personal vote”.

Of course the UK MEPs may not take their seats, or may take them only for a short period of time. Assuming the UK leaves the EU, some other countries are electing “shadow MEPs” who will effectively take up the empty seats in the parliament on the UK’s departure.

European elections in the UK are rarely about Europe. They are generally seen, by journalists, campaigners and public alike, as massive opinion polls. In fact I have seen some campaign leaflets in the past which fail to mention the parliament at all.

This time however, the elections are about Europe, although they are generally about decisions MEPs have no power to take. So a vote for the Brexit party, for example, won’t give its MEPs the power to speed up Brexit (the European Parliament can’t do this). However people vote though, will act as a signal to the UK government and House of Commons about what they think of the current state of play with Brexit.