The appeal of Donald Trump mystifies many people. How can this monstrous egotist, this apparent man-baby, be president of the United States, they wonder. But perhaps people are looking in the wrong places for answers and explanations.

They compare him to other politicians, and find that he is so different to his White House predecessors that such comparisons make no sense. But what if we were to think of Trump not as a politician, but as a kind of artist, unconsciously channelling a long legacy of radical provocation?

In this way, perhaps, he becomes more comprehensible. After all, Trump’s whole modus operandi is based on shock and confrontation.

Such an approach to life can be traced back to many historical figures, like the Marquis de Sade or, in the 19th century, the painter James McNeill Whistler. Whistler’s painting, Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket, incensed the critic John Ruskin who believed it was slapdash and meaningless. He accused the artist of “impudence” and “flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face”.

Whistler sued Ruskin for libel, leading to one of the most notorious court cases of the time. The jury decided in Whistler’s favour, but awarded him a farthing in damages, which bankrupted him.

This wasn’t just about personal reputation, it was a battle for the soul of art, with Ruskin defending its traditional social responsibilities and value, and Whistler believing in “art for art’s sake” – a belief shared by Whistler’s friend Oscar Wilde.

Art for art’s sake

The nihilistic violence of art without social responsibility found its strongest expression in the French writer Andre Breton’s proclamation:

The simplest Surrealist act consists of dashing down the street, pistol in hand, and firing blindly, as fast as you can pull the trigger, into the crowd.

The German critic Walter Benjamin believed that art for art’s sake led to the idea of war as a kind of pure, aesthetic experience, as proclaimed and celebrated by Fascism. Writing in the mid-1930s, he was aghast at what he described as the “aestheticisation of politics”, most explicitly manifested in the spectacular displays of power in Nazi Germany.

The appalling tragedy of Nazi spectacle repeats itself as farce in the 1970s, with the emergence of rock music as pure spectacle, devoid of all 1960s idealism – particularly in the glam rock of Alice Cooper and David Bowie.

Bowie went on to make the connection between rock as spectacle and fascism explicit. As far back as 1969, he had proclaimed in an interview that Britain was “crying out for a leader” and named Enoch Powell as a potential candidate. In later interviews, he compared (his alter ego) Ziggy Stardust to Hitler. Then, in 1976, in Rolling Stone magazine, he proclaimed: “I could have been Hitler in England… I think I might have been a bloody good Hitler. I’d be an excellent dictator.”

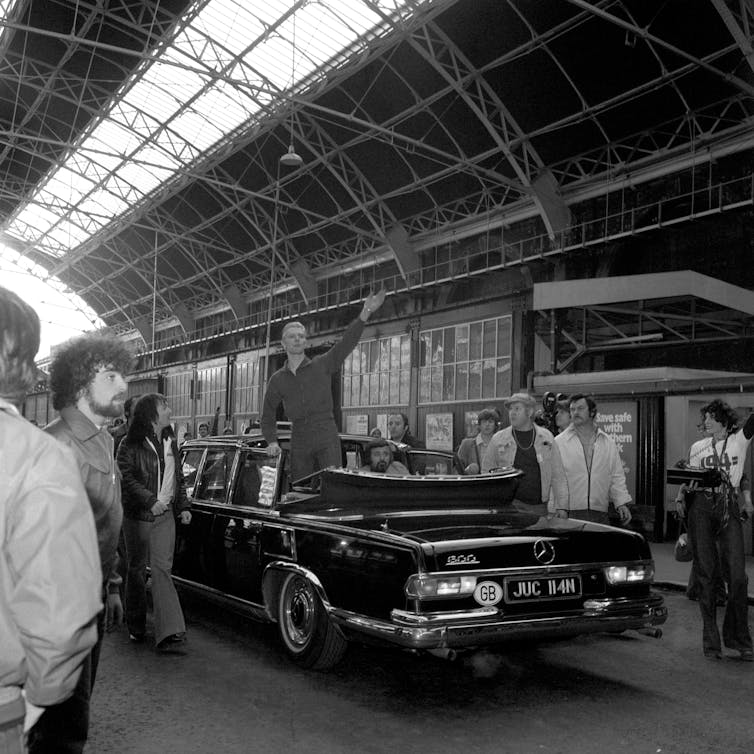

It was in the same year that he returned to England on the Orient Express, arriving at Victoria Station to be met by an open-top Mercedes, a favoured form of transport for the Nazis. This was the notorious occasion when he may or may not have made a Nazi salute to the crowd, a time he later looked back on with regret.

Bowie greets the crowd in 1976. PA/PA Archive/PA Images

Bowie greets the crowd in 1976. PA/PA Archive/PA Images

Perhaps the strangest thing about reading these proclamations by Bowie is how reminiscent they are of Trump. In a sense, Trump is the heir of Bowie, in a journey from Whistler’s 19th century aestheticism to the sometimes right wing nihilism of the early 20th century, and onto the current occupant of the White House.

Trump (born June 1947) and Bowie (born January 1947) were of the same generation. They even both hung out at nightclub Studio 54 in New York in the 1970s and 80s, though I do not know if they were ever there at the same time. Whatever the truth of Bowie’s politics, or Trump’s for that matter, both understood something profound about our contemporary culture – that image is everything.

The rock band Alice Cooper also understood this and their 1972 single Elected explicitly relates to politics. Watching the video in 2019 is an eerie experience, given the degree to which it seems to predict the emergence of politics as showbiz, and the rise of Trump.

But perhaps Trump is less like Bowie or Cooper, and more like one of Bowie’s most notorious fans – Sid Vicious, the ultimate punk, and inheritor of the mantle of avant-garde nihilism and violence.

The alt-right provocateur Milo Yiannopoulos often invoked punk rock in talking about his shock strategies. “Being a Donald Trump supporter is the new punk,” he once proclaimed, adding:

It’s the new cool thing to do. What do you do if you wanna piss off your teachers, piss off your parents, piss off your friends, be ejected from polite society, and in all other ways be thought of as an untouchable miscreant? Vote for Donald Trump.