Have you ever tried walking on a travellator? You know, those moving platforms at airports that help you get to your destination when you are in a hurry or tired, or have a lot of baggage to carry. Have you also tried to walk in the wrong direction on it? Depending on your own pace and the speed of the travellator, you could either make slow progress, or no progress at all, or go backward.

Climate Change: A Clear and Present Danger

READ MORE

This is the image I have of the last few Conferences of the Parties (COP) of the United Nations. To keep the analogy going, let’s think of the travellator as climate change, which seems unstoppable and is, in fact, getting faster.

The COP Summits

At the COP summits, representatives of almost 200 countries get together over a week or so. They discuss the latest data on climate change, global greenhouse gas emissions and then negotiate on the required actions to address climate change — move forward on the travellator — and reduce greenhouse gas emissions, assist developing countries in achieving emissions reductions and adapt to a changing climate.

But it hasn’t been easy, and it never was going to be easy. As I explain in my book, “A Climate for Denial,” climate change is classified as a wicked problem — one that is complex, ever-changing, difficult to define and involving multi-disciplinary aspects, constraints and solutions. But it is also one that must be addressed and solved.

So, these COP summits are organized to see what, if anything, can be done. But these meetings and negotiations are often bogged down in detail and lack of agreement even on fundamental issues. These include how to account for greenhouse gas emissions and how to allow developing countries to develop economically without penalizing them, while developed countries defend their right to maintain their high dependency on energy usage and economic prosperity.

Due to the huge discrepancies between developed, developing and underdeveloped countries in their emissions profiles, economic development, and technical and economic capabilities, negotiations can rarely get past first base. A fundamental roadblock preventing progress has been because of the complexities of allowing developing countries to catch up with developed countries while reducing global emissions of greenhouse gases.

That’s why the 2015 Paris accord relies on a vague agreement to keep global warming to within 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. When that agreement was signed in 2016, every country was asked to determine its own target and pledge to meet it, which would supposedly achieve the overall 1.5-degree goal. The Paris accord is a vague agreement mainly because it’s not legally binding and, therefore, doesn’t guarantee its intended achievement. The end result speaks for itself: emissions continue to rise and global warming is not stopping.

The whole idea of voluntary action on an extremely complex issue such as the reduction of global emissions is therefore fraught with manipulation, loopholes and lack of urgency due to national priorities and interests ahead of global interests. A great example of this is Australia’s insistence to use the 1997 Kyoto Protocol’s “left-over” credits to meet its Paris targets. This clearly is against the spirit of the Paris Agreement as it tried to be forward-looking, having drawn “a line in the sand” on where emissions were in 2015-16 and where they needed to be in the future. It’s equivalent to telling someone that they need to lose weight for their health, and then the person saying they’ve lost weight over the past few years.

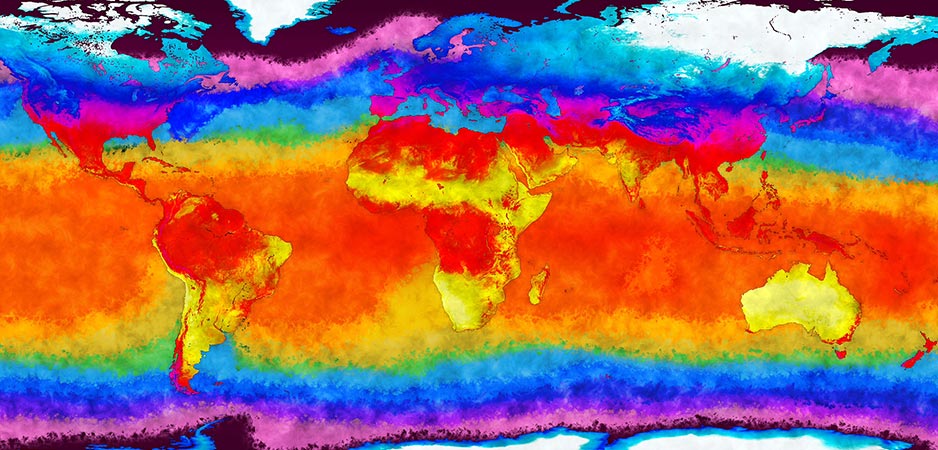

One of the greatest challenges in these negotiations and agreements has been the huge discrepancies in the emissions profiles, energy requirements and economic development between countries. On the one hand, we have nations that have still to provide electricity to large areas of their population and, on the other, developed countries that rely primarily on fossil fuels and emit proportionally large amounts of greenhouse gases per capita.

COP25 in Madrid

So, what was COP25 meant to achieve — which took place in Madrid earlier this month — and what did it actually achieve? The main aims of the climate conference were to finalize the rules by which the Paris targets are achieved and begin the processes by which the commitments made in December 2015 could be systematically raised. There were also a host of technical matters related to carbon markets, as well as details on how poorer countries would be compensated for climate-related damage.

The achievements of the COP25 summit could only be classified as decisions, not achievements. They were mainly to do with initiatives to foster mitigation and adaptation relating to oceans and land; funding for the repair of damage and loss to help poor countries that are suffering from the effects of climate change — although there was no allocation of new funds to do so; periodic review of the long-term 2-degree target starting in 2020; and establishing a few rules to do with carbon markets.

But many questions and issues remained unanswered, unresolved and left for future meetings. The agenda for the next conference (COP26) in November 2020, to be hosted by the UK in partnership with Italy, will once again be filled with ambition and promise, and circular discussions.

I know this is going to sound somewhat cynical, maybe very cynical to some, but my summary of the COP processes, so far, can be summarized as follows:

Meeting 1: Let’s all get together and talk about this problem of global warming and climate change.

*many meetings later*

Meeting…: Different countries seem to have different viewpoints and problems, so these meetings are really useful to get some consensus.

Meeting…: Let’s agree to do something positive.

*a few meetings later*

Meeting…: We’re getting somewhere, why don’t developed countries help developing countries and get credit for doing this (Kyoto).

*a few meetings later*

Meeting…: Time is running out, this is getting serious, really serious!

Don’t get me wrong, there has been considerable progress made all around the world on the installation of large, renewable energy generation systems, and this has meant some improvement in balancing economic development of countries that are still catching up with the highly-industrialized nations. But, in reality, such progress hasn’t been adequate.

So, back to our analogy. While the travellator continues to take the world backward in terms of emissions reductions, global action is limited to meetings, targets and pledges.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.