The entertainment media cooperative considers itself a ‘post-capitalist’ streaming service – and a critical counterweight to rightwing media

Illustration: Guardian Design/The Guardian

Naomi Burton and Nick Hayes met at a meeting for the Detroit chapter of the Democratic Socialists of America. Both were working for automakers in the city: Hayes created freelance video content for them while Burton ran social media for the same companies. Together, they launched Means of Production, a media company that would take no corporate clients.

Five months later, they made Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s viral Courage To Change video. The social capital they accrued, plus a bit of savings, led them to launch Means TV – a worker-owned, leftist entertainment media cooperative, supported entirely by subscriber money. As of 7 April, they have 3,700 subscribers, most of whom pay the full fee of $10 a month, though Burton notes that they “always offer discounted subscriptions to anyone who can’t afford it”.

Burton and Hayes describe Means TV as a “post-capitalist” streaming service. “We can start projecting a vision beyond capitalism, and couch our entertainment within this idea of imagining a reality similar to our own, but without the corrosive and toxic effects of capitalism,” says Hayes.

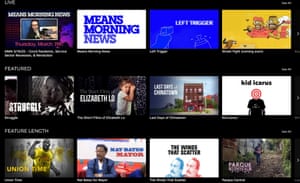

The interface for Means TV reminds one of a pared-back Netflix, with content divided by format: full-length films, series, comedy, animation, even kids’ content. Wrinkles and Sprinkles, for example, is a kids’ show which finds two cats – one a crusty, wisened elder and one a peppy kitten – learning about direct action and solidarity. Feature-length documentaries detail the Palestinian resistance movement, invasive swamp rats threatening the Louisiana coast’s communities and culture, and indigenous children in Guatemala dodging police in the city while finding ways to provide for their families.

Means follows a simple metric for determining suitability of content: “Is this punching up or down? Is this going after people that have more power than us, or is this denigrating people that have less power than us?”

David Jackson, an instructor in Carleton University’s communications department and organizer with the collective Improvising Musicians of Ottawa, says Means provides a critical counterweight to rightwing media. “There has to be a counter to Breitbart and the ‘alt-right’ [media] who seem to have a command both on social media and through the press,” says Jackson. “The political stakes are becoming really, really clear that it is, as it always has been, a matter of life and death.”

While we’re usually able to discern between ideological biases in news media, entertainment media is less overtly politicized. But Hayes and Burton say there are subtle ideological markers which make entertainment an effective “cultural reproduction tool”.

They cite the example of the sitcom Friends, which depicted a group of working-class New Yorkers who somehow occupied an enormous apartment. From a young age, Burton couldn’t understand why she – also from a working-class background – didn’t have access to the sort of leisure time and aesthetic pleasures that the characters in the show did. “Even Full House, it’s like, ‘Damn, look at their house, these people seem to be regular working people, but their cars aren’t weird minivans like mine,’” says Burton. “It totally distorts your idea of the kind of life you’re supposed to live, the way you’re supposed to look, the way you’re supposed to act. We don’t realize we’re being given a political framework from which to look at the world.”

Los Angeles-based director, comedian and writer Sara June, who works full-time with Means TV, notes that the accessibility of digital media and affordable production options have enabled working-class entertainment media creators to find success. “It’s never been possible before to do something like this with such a small amount of money,” says June. “People without a lot of money didn’t get to make media, and that used to be tied to the mechanics of making media. A worker-owned media has never been possible with video before.”

The co-op is divided into three tiers, which determine the percentage of end-of-year profits each worker member gets. Full-time worker members get 70%, contractor members get 20% and royalty members get 10%.

Washington DC-based journalists and podcast creators Sam Sacks and Sam Knight host Means Morning News, a weekly news show that airs on Means TV. Sacks says that years of neoliberal policy and broadening class gaps have made leftist ideology more palatable. “The conditions in this country have deteriorated so much, going back decades. People are desperate to figure out why things are breaking down and how we can build a new world.” Knight says young people are interested in leftwing ideas “in ways that the United States hasn’t seen in decades”.

Means arrives amid brutal layoffs across US newsrooms, which have increasingly unionized in the past five years. Calls abound for more worker-owned media, and the In These Times labor reporter Hamilton Nolan, who has written for the Guardian, observes that the trend is the product of firsthand experience in poor working conditions. “You had all these workers going through the experience themselves and getting class consciousness in a sense,” says Nolan.

For inspiration, American media workers can turn to successful co-op efforts abroad. When the Argentinian newspaper owner Sergio Szpolski decided to shutter Tiempo Argentino in late 2015, the workers pooled their money to keep it alive as a co-op. Javier Borelli, general information editor with Tiempo Argentino and elected member of the co-op’s executive board, was there during the transition – a period that saw the paper’s offices attacked by a group of 20 men.

“We were very committed to the idea of doing something that could be ours, and we had the energy and time to spend in this situation,” says Borelli. He acknowledges starting the co-op was a risk made possible by situational factors, like most of the workers being young and without families to provide for.

Tiempo Argentino, which is 70% reader-funded, is one of thousands of worker-recovered enterprises across Argentina. “We followed the examples of the recovered enterprises that started in Argentina in the 1990s,” says Borelli. When neoliberal measures forced private domestic businesses to close in the face of rising imports, workers reopened them as co-ops.

“Personally, I think it’s the right way,” says Borelli. He studied worker-owned, explicitly leftist media models in France and Spain, including France’s Mediapart which is governed by a non-profit trust that guarantees editorial independence. Borelli found that 95% of its revenue came from readers. The paper’s slogan is appropriate: “Only our readers can buy us.”

Hayes says they would like to develop similar models in radio and video games to give those industries alternatives to relying on advertising, “or some billionaire”. Right now, these concepts seem like tall asks. But June points out: “We’re not trying to do anything incredibly radical. We’re trying to create media in a space where there’s a democratic workplace and everybody gets paid for what they do. You’d be surprised at how revolutionary that is.”