‘What it means to be an American’: Abraham Lincoln and a nation divided

Amid a new crisis, Ted Widmer’s book on the 16th president’s journey to Washington in 1861 may prove timely indeed

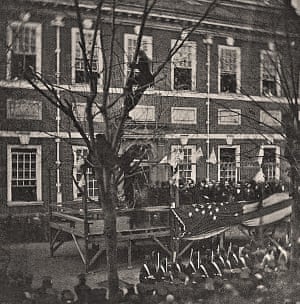

Photograph: Bettmann Archive

Ted Widmer has published a book about a time of national crisis, in a time of national crisis.

Lincoln on the Verge follows the 16th president on his 13-day journey to Washington in February 1861, civil war imminent, the union falling apart. Almost 160 years later, a coronavirus outbreak has killed 17,000 Americans and infected hundreds of thousands more.

Widmer, distinguished lecturer at Macaulay Honors College of the City University of New York, will not be riding the rails himself, to college towns and bookstores.

“It’s surreal,” he says, from lockdown in Rhode Island. “I still have one [event] at the Lincoln Presidential Library in Springfield, Illinois. That’s not until June.

“I’m just biding my time and trying to talk about the book. I just started an Instagram for the first time in my life. So, I’m trying to do my part.”

A conversation with Widmer would be fascinating in less trying times – or more. He speaks with evident delight of a common phenomenon: a fascination with Lincoln formed “as a fourth-grade boy”, on reading “a picture biography” and “feeling drawn even to his face”.

Lincoln is the president who really did come from nothing, who went to Washington from what was then the wild and unruly west, who spoke of government of the people, by the people, for the people, who oversaw the preservation of the union and the end of slavery, and who was killed in cold blood on Good Friday 1865.

“There is this feeling of sadness inside Lincoln that we don’t get with most of our famous leaders,” Widmer says. “And this sadness shows a deeper capacity for reason and someone who’s experienced a great deal in life, which was true.

“Later I graduated to reading his speeches and so many of them are beautifully written. I think we still consider him the most eloquent of our presidents.”

Widmer wrote speeches for Bill Clinton and advised Hillary Clinton when she was secretary of state. He happily accounts himself a “speech nerd”, so we happily discuss one of Lincoln’s lesser-known addresses, which he gave at Independence Hall in Philadelphia on 22 February 1861.

But there’s something to get out of the way. The place of Lincoln, and books about him, in a nation jaggedly divided again.

Lincoln’s life, Widmer says, “is a story of incredible survival against adversity. And more than survival, really, sort of winning on every possible front. And whenever we fail again, which we do pretty routinely, I think he still speaks to us and helps us to be better than we might be otherwise.”

You may see where this is heading. Covid-19 is ravaging the land and to some Lincoln’s successor in the White House, the 45th president, seems to be losing the fight.

I ask the inevitable question, prompted by interviews with historians of Lincoln and Frederick Douglass but also the Holocaust and Jean-Paul Sartre. Does Widmer’s book contain lessons for readers in America under Trump?

“Well,” he says, picking his words with care, “I hope it does. I think one of the reasons we read history is for insights into our present.”

Maybe such caution is born of Widmer’s Clintonian background – he’s an alumnus of the same White House as Sidney Blumenthal, now three volumes into a five-volume life of Lincoln but a bete noire for many Trump supporters. Maybe it isn’t. Widmer continues.

“I don’t want to be too nakedly political. I want to reach out to all Americans from all backgrounds, I really do. While writing this book I was conscious of how much I learned from my Republican grandmother.

“I think Lincoln’s example shows how important it is to be an ethical person, which he was, very unusually for politicians in his own time as well as ours. He was uncomfortable talking about himself and he tried to give the credit to others.

“But he also had a long view. He tried to say to Americans, ‘It’s really important to get democracy right, because so many other people are depending on us, not just people in this country, with and without political rights, but other countries who are trying to become more democratic.’

“… And he was thinking a lot about the future too. He mentions the 20th century in a few speeches. And so I think he was trying to reach out to us. And I think we should not be ashamed about looking back to him.

“How can we be the most ethical people? How can we choose the wisest leaders? How can we get back to factuality? There are facts that bolster Republican arguments and there are facts that bolster Democratic arguments. But to at least admit the facts will make us a better country.”

‘The most sublime statement’

Back to Philadelphia. I suggest Lincoln’s speech there in 1861 should be better known.

Before Independence Hall, Lincoln had spoken as a candidate, in his great debates with Stephen Douglas, and he had spoken as a lawyer, when he went to Cooper Union in New York and took the case for slavery to pieces. But when he spoke in Philadelphia, he spoke as a leader – as the president he was about to become – for the very first time.

The key to the speech lies in the simple statement that Lincoln “never had a feeling politically that did not spring from the sentiments embodied in the Declaration of Independence”.

It’s actually a lawyerly bit of phrasing, a neat dodge of those who point out that the Declaration doesn’t say “women” and that Thomas Jefferson, the man who wrote “all men are created equal”, owned slaves himself.

Widmer calls it “the most sublime statement of what it means to be an American, of the human rights that belong, in fact, to all people on Earth.

“And Lincoln says it beautifully and in a very short speech, but by doing that he brilliantly takes the problems of 1861 and sets them in a much wider frame. He also sidesteps the constitution with all of its awkwardness on racial questions and slavery and he just goes right to the core of the national experiment, that we are trying to make democracy work for all people. Because slavery was a complete contradiction of those claims to human rights inside the Declaration.

“It was a pretty short distance from that speech in 1861 to the Gettysburg Address in 1863. So I argue that he really had worked out something very important.”

Widmer started out aiming simply to portray “Lincoln moving in a fast-moving conveyance, a train, in a very dangerous situation”. It “felt cinematic”, he says, and indeed it does, as the places Lincoln saw – Indianapolis, Cincinnati, Baltimore and its nests of would-be assassins – slide past.

But then he “realised Lincoln was changing in important ways along the way and Philadelphia’s the key to that. He’s giving better and better speeches, though there were a couple clunkers, and I like that because it shows a human Lincoln.

“He gave a very bad speech about the economy in Pittsburgh and he nearly lost his inaugural speech in Indianapolis. He had a lot of problems. But then he starts about what it means to be an American.”

Around Lincoln’s odyssey, quoting Homer liberally, Widmer wraps a richly written account of the concurrent journey of the Confederate president, Jefferson Davis; diversions on train-travel in the 19th century (Widmer is a passionate defender of 21st-century Amtrak); and portrayals of those who Lincoln met, who recorded their thoughts in diaries, letters and long-lost local papers.

There is also “a lot about the building, Independence Hall, and what a difficult history it had”.

“At a time when Americans are being whipsawed by the news, Lincoln goes into the most sacred building of American political history, where the Declaration of Independence was written and signed, and he gives an absolutely beautiful speech on George Washington’s birthday about how this is the document that has guided him throughout everything he’s ever done in politics.

“But in fact, [the hall] had been used as a holding pen for African Americans in the 1850s who were being recaptured. They would make it to Philadelphia and to freedom in the Underground Railroad, and then they would be recaptured, often even if they were legitimately free, they would be incarcerated in a jail inside the Independence Hall, and sent back into the south.

“So that building had become tainted in the eyes of a lot of Americans. And Lincoln, I argue, cleansed it and gave it back its integrity.”

A tour of Independence Hall is a moving experience. But on the bright February morning when I took one, at least, that dark chapter was not mentioned.

Though the life and times of Abraham Lincoln have been exhaustively studied, new approaches are still to be found.