There is one big thing missing from the latest inquest into Labour’s election defeat: politics. The report, from a group called Labour Together which includes Ed Miliband, tells the party what it already knows. It fought a badly organised campaign last year and faces a “mountain to climb” at the next election.

The report tiptoes around the causes of defeat. “The roots of our 2019 loss stretch back over the last two decades,” it says, referring to “political alienation, demographic change and cultural shifts”. This is bunk. Demography is not destiny. Elections are choices, shaped by parties and leaders.

If we go back two decades, as invited by the report’s authors, that takes us to 1999, which is an interesting starting point. This is the infuriating Corbynite trick of taking the biggest peacetime election win for granted and then complaining that Tony Blair led the party downhill after that.

Download the new Independent Premium app

Sharing the full story, not just the headlines

But the roots of last year’s defeat don’t even stretch back one decade, to 2009, when Labour could have ditched Gordon Brown, and David Miliband or Alan Johnson could then have won more votes in the 2010 election. As it was, 2010 resulted in a hung parliament. There was nothing preordained about it, nothing in the “roots” that said Labour had to lose – and it almost didn’t. The same applies to the 2017 election.

I have a simple test of any analysis of Labour’s 2019 defeat, which is: can you explain how Labour very nearly won in 2017? It is a test that the Labour Together report fails. It implies that the tides of demography and culture have been running against the party since the Middle Ages, and that the foundations of the red wall seats of the north, midlands and north Wales were already rotten.

In that case, how did Labour come within 10 seats of making Jeremy Corbyn prime minister in 2017? This is a question that is sometimes met with disbelief, partly because I had undertaken not to mention the previous leader’s name, but mostly because people, and especially Blairites, misremember the election before last.

However, I will have to reverse my policy of pretending that the last five years of Labour history simply didn’t happen. Comforting as it may seem for those of us who were opposed to Corbyn and everything he stood for, it is unhealthy to join in what will soon be the common amnesia about that period. It was a shameful interlude, and it may be that in a few years’ time no one will remember being part of it.

But it is important to remember it precisely because it was shameful. We need to remember that Corbyn suggested Israel shouldn’t exist; that he called Hamas friends; that he refused to condemn the IRA; and that he praised George Lansbury for advocating disarmament during the Second World War.

It is also important to remember it precisely because Corbyn came so close to winning. Of course he was a long way from a majority Labour government, but if Theresa May had lost another 10 seats or so, she and the DUP could not have governed. I do not believe that more than two or three Labour MPs would have voted to keep her in No 10 rather than allow Corbyn to cross the threshold.

So what does the Labour Together report say about coming so close to victory? “The 2017 result masked continuing underlying voter trends in Labour’s historic voter coalition.” It is a bit like saying Marcus Rashford is a really good footballer, but he’s not getting any younger, you know.

What is missing from the Labour Together report is politics. Labour did well in 2017 because Corbyn caught the moment. He offered idealism and change: more money for schools and a chance to stop Brexit. Theresa May turned out to be frit and useless during the campaign, and promised to take old people’s homes away from them.

1/50 19 June 2020

Nurses, doctors, midwives and health care workers attend the fourth Zumba dance session organised by the Nursing Council of Kenya at Kenyatta stadium where screening booths and an isolation field hospital have been installed. The dance sessions have been organised to re-energise and uplift health care providers sprits during this pandemic

AFP via Getty

2/50 18 June 2020

Alpha jets from the French Air Force Patrouille de France and the Royal Air Force Red Arrows perform a flypast over the statue of Charles de Gaulle on the Champs Elysees avenue in Paris to celebrate the 80th anniversary of wartime leader’s appeal to the French people to resist the Nazi occupation, broadcast from London

Reuters

3/50 17 June 2020

Activists from the Extinction Rebellion movement block a street outside the German Automobile industry association during a protest in Berlin

AFP via Getty

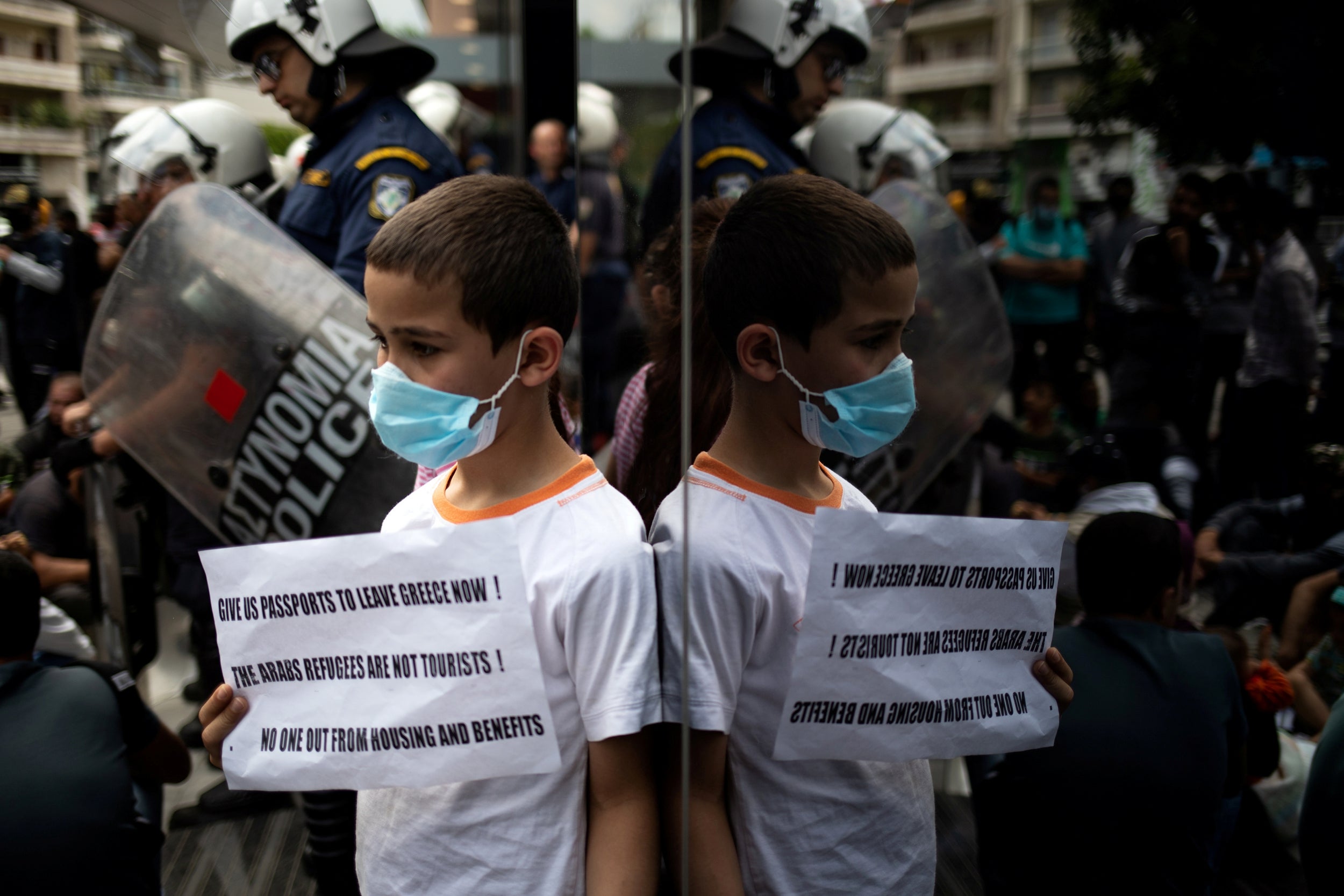

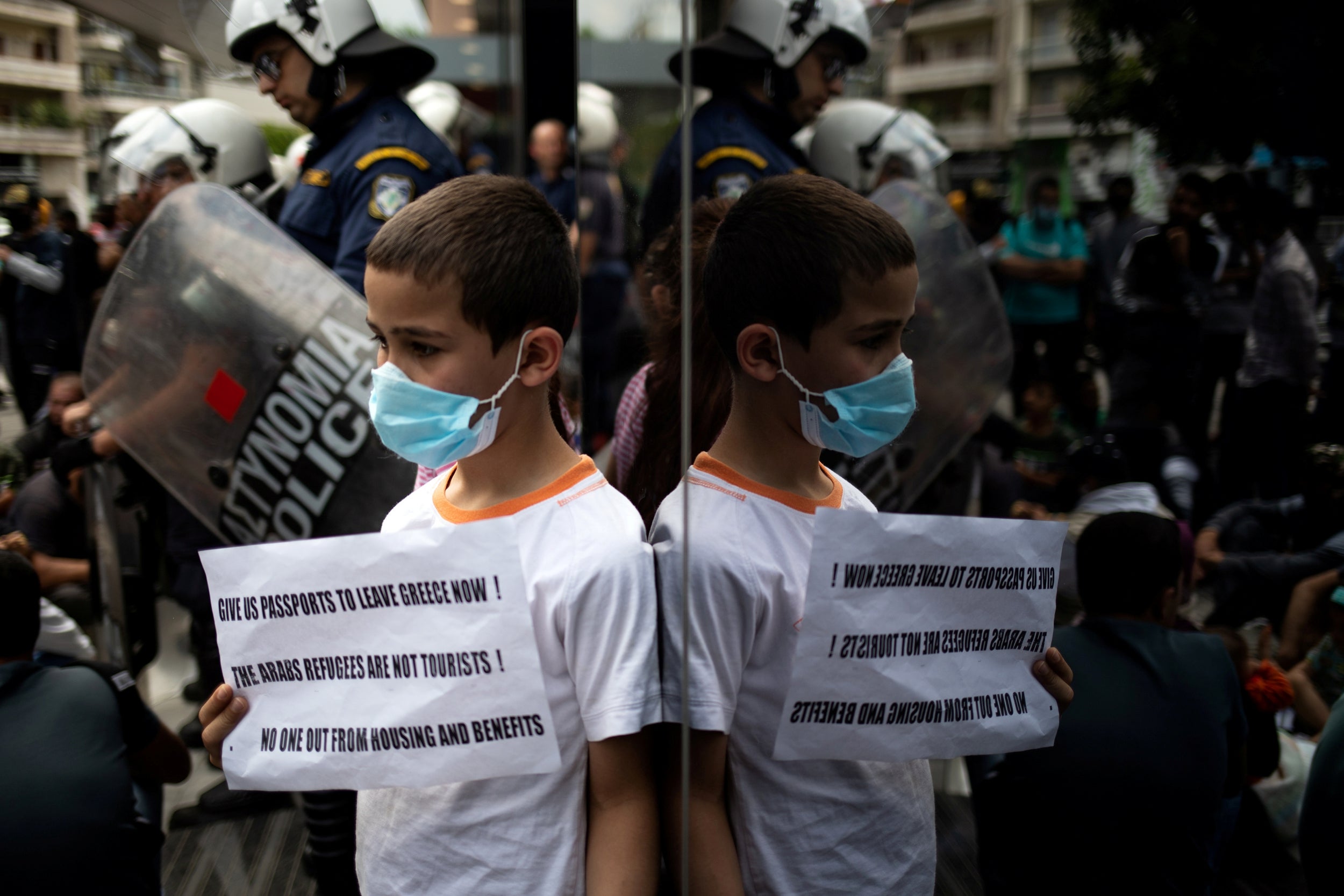

4/50 16 June 2020

Barbers wearing protective suits and face masks inside a salon in Dhaka, Bangladesh

Reuters

5/50 15 June 2020

Siegfried White raises his hand as he protests outside a burned Wendy’s restaurant on the third day following Rayshard Brooks death. The black man was shot by police in the car park in Atlanta. The mayor ordered immediate police reforms on Monday after the fatal shooting by a white officer

AFP via Getty

6/50 14 June 2020

People take part in a Black Lives Matter protest march in central Tokyo

AFP via Getty

7/50 13 June 2020

Protesters raise their fists during a demonstration against police brutality and racism in Paris, France. The march was organised by supporters of Assa Traore, whose brother Adama died in police custody in 2016, in circumstances that remain unclear

EPA

8/50 12 June 2020

A pro-democracy supporter shouts at riot police during an anti-national security law rally in Mongkok district in Hong Kong, China. Protesters heeded online calls to gather as the city marks the one-year anniversary of the major clashes between police and pro-democracy demonstrators over the controversial extradition bill

Getty

9/50 11 June 2020

A section of the River Spree next to the Reichstag building coloured green by activists from “Extinction Rebellion” to protest the German government’s coal policies in Berlin

AFP via Getty

10/50 10 June 2020

A woman poses in front of a decapitated statue of Christopher Columbus at Christopher Columbus Park in Boston Massachusetts. The statue’s head, damaged overnight, was recovered by the Boston Police Department, as a movement to remove statues commemorating slavers and colonisers continues to sweep across the US

AFP via Getty

11/50 9 June 2020

Ivy McGregor, left, reads a resolution during the funeral for George Floyd at The Fountain of Praise church in Houston. George Floyd is being laid to rest in his hometown, the culmination of a long farewell to the 46-year-old African American whose death in custody ignited global protests against police brutality and racism

AFP via Getty

12/50 8 June 2020

People raise their fist and stand on their knees as they demonstrate in Nantes, during a Black Lives Matter protest

AFP via Getty

13/50 7 June 2020

A woman looks on during a protest against the killing of George Floyd in Osaka city, western Japan

EPA

14/50 6 June 2020

Demonstrator raise their fists at the Lincoln Memorial during a protest against police brutality and racism in Washington, DC. Demonstrations are being held across the US following the death of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, while being arrested in Minneapolis, Minnesota

AFP via Getty

15/50 5 June 2020

A handout photo made available by 2020 Planet Labs shows an aerial view of the large diesel spill in the Ambarnaya River outside Norilsk in the Arctic. Russia has managed to contain a massive diesel spill into a river in the Arctic, a spokeswoman for the emergencies ministry told AFP. Environmentalists said the oil spill, which took place last May 29, was the worst such accident ever in the Arctic region

Planet Labs Inc./AFP via Getty

16/50 4 June 2020

Activists hold a candlelit remembrance outside Victoria Park in Hong Kong, after the annual vigil, that traditionally takes place in the park to mark the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown, was banned on public health grounds because coronavirus

AFP via Getty

17/50 3 June 2020

A visitor walks in Odaiba as the sun sets in Tokyo

AP

18/50 2 June 2020

Activists of the Socialist Unity Centre of India shout slogans in Ahmedabad in solidarity with protests against the recent killing of George Floyd

AP

19/50 1 June 2020

Activists take part in a Black Lives Matter protest in Zurich after the recent death of George Floyd

EPA

20/50 31 May 2020

A black man and a white woman hold their hands up in front of police officers in downtown Long Beach during a protest against the death of George Floyd, an unarmed black man who died while being arrested and pinned to the ground by the knee of a Minneapolis police officer. Protests sweeping the United States over the death of George Floyd reverberated on the other side of the globe when thousands marched in solidarity on the streets of New Zealand

AFP via Getty

21/50 30 May 2020

Police officers are seen amid tear gas as protesters continue to rally against the death in Minneapolis police custody of George Floyd, in Minneapolis, Minnesota

Reuters

22/50 29 May 2020

A boy holds a sign as refugees protest outside the UNHCR offices against a government decision that they should leave their accommodation provided through European Union and UNHCR funds by the end of May, in Athens, Greece

Reuters

23/50 28 May 2020

Cloud iridescence, an optical phenomenon where light is diffracted through water droplets, is pictured at the edge of some clouds before a summer thunderstorm over Bangkok

AFP via Getty

24/50 27 May 2020

Riot police try to control pro-democracy supporters at a rally in Causeway Bay district, Hong Kong

Getty

25/50 26 May 2020

Protesters and police face each other during a rally after a black man died in police custody hours after a bystander’s video showed an officer kneeling on the handcuffed man’s neck, even after he pleaded that he could not breathe and had stopped moving

Star Tribune via AP

26/50 25 May 2020

The aerobatic demonstration team ‘Frecce Tricolori’ of the Italian Air Force flies in formation above the Milan Cathedral. Starting from 25 May, the Frecce Tricolori will perform every day in the skies throughout Italy as part of the 74th anniversary celebrations of the founding of the Italian Republic and to pay homage to the areas most affected by the coronavirus

EPA

27/50 24 May 2020

Saudi Arabia’s holy city of Mecca during the early hours of Eid al-Fitr, the Muslim holiday which starts at the conclusion of the holy fasting month of Ramadan

AFP via Getty

28/50 23 May 2020

Tamika Eastley, left, and Anthony Ragusa work out as the sun sets over the Kangaroo Point Cliffs in Brisbane, Australia

EPA

29/50 22 May 2020

Firefighters spray water on the wreckage of a Pakistan International Airlines aircraft after it crashed into a residential area in Karachi

AFP via Getty

30/50 21 May 2020

Indigenous leader Kretan Kaingang wears a face mask with a hashtag that reads in Portuguese: “Get out Bolsonaro” during a protest demanding the impeachment of President Jair Bolsonaro outside the National Congress in Brasilia, Brazil, Thursday, May 21, 2020. As Brazil careens toward a full-blown public health emergency and economic meltdown, opponents have filed a request for Bolsonaro’s impeachment based on his mishandling of the new coronavirus pandemic. (AP Photo/Eraldo Peres)

AP

31/50 20 May 2020

People wait in line to undergo the coronavirus tests while keeping distance from each other at a makeshift clinic set up on a playground in Incheon, South Korea

Yonhap/AP

32/50 19 May 2020

Firefighters fighting a fire at a plastics factory in front of a huge cloud of smoke in Ladenburg, Germany

dpa via AP

33/50 18 May 2020

Ugandan academic Stella Nyanzi reacts as police officers detain her for protesting against the way that government distributes the relief food and lockdown situation in Kampala

Reuters

34/50 17 May 2020

A woman sits alone on a bench in a park following the outbreak of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19), in Dublin, Ireland

Reuters

35/50 16 May 2020

Crematory workers using protective gear are pictured at a crematory in Nezahualcoyotl during the outbreak of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19), on the outskirts of Mexico City, Mexico

Reuters

36/50 15 May 2020

Healthcare workers, nurses and doctors, unified under the movement called “Take Care of Care” wearing face masks protest against the Belgian authorities’ management of the coronavirus crisis, at the MontLegia CHC Hospital

Reuters

37/50 14 May 2020

A girl watches over goats on the banks of the Dal Lake during rainfall in Srinagar

AFP via Getty Images

38/50 13 May 2020

Life-size cardboard figures with photos of football fans are positioned on the stands of Borussia Moenchengladbach’s football stadium for their next game, which will be played without spectators, due to the coronavirus outbreak in Germany

Reuters

39/50 12 May 2020

Nurses wearing face masks take part in an event held to mark International Nurses Day, at Wuhan Tongji Hospital in China

China Daily via Reuters

40/50 11 May 2020

Iraqi protesters gather on the Al-Jumhuriyah bridge in the capital Baghdad during an anti-government demonstration. Modest anti-government rallies resumed in some Iraqi cities Sunday, clashing with security forces and ending months of relative calm just days after Prime Minister Mustafa Kadhemi’s government came to power. The protests first erupted in Baghdad and Shiite-majority southern cities in October, demanding an end to corruption and unemployment and an overhaul of the ruling class

AFP via Getty

41/50 10 May 2020

A man wearing a mask walks his dog in Madrid during the hours allowed by the government to exercise. Spain’s two biggest cities, Madrid and Barcelona, will not enter the next phase out of coronavirus lockdown along with many other regions next week

AFP via Getty

42/50 9 May 2020

Russian President Vladimir Putin addresses the nation after laying flowers at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier near the Kremlin wall in Moscow, Russia. Russia marks the 75th anniversary since the capitulation of Nazi Germany in WWII amid the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic

EPA

43/50 8 May 2020

German Chancellor Angela Merkel, President of the German Parliament Bundestag Wolfgang Schaeuble, German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier, President of the Federal Council Bundesrat in Germany Dietmar Woidke and the presiding judge of the German Federal Constitutional Court’s second senate, Andreas Vosskuhle attend wreath-laying ceremony to mark the 75th anniversary of the end of World War Two, at the Neue Wache Memorial in Berlin. Countries in Europe are commemorating the Victory in Europe Day, known as VE Day that celebrates Nazi Germany’s surrender during World World II on 8 May 1945

EPA

44/50 7 May 2020

A policeman uses his baton to push a resident breaking rules, during an extended nationwide lockdown to slow down the spread of coronavirus in Ahmedabad, India

Reuters

45/50 6 May 2020

A nurse tends to a crying newborn baby wearing a face shield at the National Maternity Hospital in Hanoi

AFP via Getty

46/50 5 May 2020

Bride Janine runs over to her wedding at a Drive-in cinema in Duesseldorf, Germany. The Drive-in theatre started to register official marriages on a stage, allowing all relatives and friends to attend in their cars, as weddings at the registry office are limited due to the coronavirus pandemic

AP

47/50 4 May 2020

Storekeepers asking for the reopening of shops and commercial activities gather for a flashmob protest on Piazza San Marco in Venice, as Italy starts to ease its lockdown

AFP via Getty

48/50 3 May 2020

A street vendor wearing a protective face mask waits for customers in Chinatown, after the government started opening some restaurants outside shopping malls, parks, and barbershops in Bangkok, Thailand

Reuters

49/50 2 May 2020

Two women carry longboards on an esplanade in Barcelona, during the hours allowed by the government to exercise, for the first time since the beginning of a national lockdown. All Spaniards are again allowed to leave their homes since today to walk or play sports after 48 days of very strict confinement to curb the coronavirus pandemic

AFP via Getty

50/50 1 May 2020

A girl, wearing a protective mask, plays with bubbles at a shopping mall in Gimpo, South Korea

Reuters

1/50 19 June 2020

Nurses, doctors, midwives and health care workers attend the fourth Zumba dance session organised by the Nursing Council of Kenya at Kenyatta stadium where screening booths and an isolation field hospital have been installed. The dance sessions have been organised to re-energise and uplift health care providers sprits during this pandemic

AFP via Getty

2/50 18 June 2020

Alpha jets from the French Air Force Patrouille de France and the Royal Air Force Red Arrows perform a flypast over the statue of Charles de Gaulle on the Champs Elysees avenue in Paris to celebrate the 80th anniversary of wartime leader’s appeal to the French people to resist the Nazi occupation, broadcast from London

Reuters

3/50 17 June 2020

Activists from the Extinction Rebellion movement block a street outside the German Automobile industry association during a protest in Berlin

AFP via Getty

4/50 16 June 2020

Barbers wearing protective suits and face masks inside a salon in Dhaka, Bangladesh

Reuters

5/50 15 June 2020

Siegfried White raises his hand as he protests outside a burned Wendy’s restaurant on the third day following Rayshard Brooks death. The black man was shot by police in the car park in Atlanta. The mayor ordered immediate police reforms on Monday after the fatal shooting by a white officer

AFP via Getty

6/50 14 June 2020

People take part in a Black Lives Matter protest march in central Tokyo

AFP via Getty

7/50 13 June 2020

Protesters raise their fists during a demonstration against police brutality and racism in Paris, France. The march was organised by supporters of Assa Traore, whose brother Adama died in police custody in 2016, in circumstances that remain unclear

EPA

8/50 12 June 2020

A pro-democracy supporter shouts at riot police during an anti-national security law rally in Mongkok district in Hong Kong, China. Protesters heeded online calls to gather as the city marks the one-year anniversary of the major clashes between police and pro-democracy demonstrators over the controversial extradition bill

Getty

9/50 11 June 2020

A section of the River Spree next to the Reichstag building coloured green by activists from “Extinction Rebellion” to protest the German government’s coal policies in Berlin

AFP via Getty

10/50 10 June 2020

A woman poses in front of a decapitated statue of Christopher Columbus at Christopher Columbus Park in Boston Massachusetts. The statue’s head, damaged overnight, was recovered by the Boston Police Department, as a movement to remove statues commemorating slavers and colonisers continues to sweep across the US

AFP via Getty

11/50 9 June 2020

Ivy McGregor, left, reads a resolution during the funeral for George Floyd at The Fountain of Praise church in Houston. George Floyd is being laid to rest in his hometown, the culmination of a long farewell to the 46-year-old African American whose death in custody ignited global protests against police brutality and racism

AFP via Getty

12/50 8 June 2020

People raise their fist and stand on their knees as they demonstrate in Nantes, during a Black Lives Matter protest

AFP via Getty

13/50 7 June 2020

A woman looks on during a protest against the killing of George Floyd in Osaka city, western Japan

EPA

14/50 6 June 2020

Demonstrator raise their fists at the Lincoln Memorial during a protest against police brutality and racism in Washington, DC. Demonstrations are being held across the US following the death of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, while being arrested in Minneapolis, Minnesota

AFP via Getty

15/50 5 June 2020

A handout photo made available by 2020 Planet Labs shows an aerial view of the large diesel spill in the Ambarnaya River outside Norilsk in the Arctic. Russia has managed to contain a massive diesel spill into a river in the Arctic, a spokeswoman for the emergencies ministry told AFP. Environmentalists said the oil spill, which took place last May 29, was the worst such accident ever in the Arctic region

Planet Labs Inc./AFP via Getty

16/50 4 June 2020

Activists hold a candlelit remembrance outside Victoria Park in Hong Kong, after the annual vigil, that traditionally takes place in the park to mark the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown, was banned on public health grounds because coronavirus

AFP via Getty

17/50 3 June 2020

A visitor walks in Odaiba as the sun sets in Tokyo

AP

18/50 2 June 2020

Activists of the Socialist Unity Centre of India shout slogans in Ahmedabad in solidarity with protests against the recent killing of George Floyd

AP

19/50 1 June 2020

Activists take part in a Black Lives Matter protest in Zurich after the recent death of George Floyd

EPA

20/50 31 May 2020

A black man and a white woman hold their hands up in front of police officers in downtown Long Beach during a protest against the death of George Floyd, an unarmed black man who died while being arrested and pinned to the ground by the knee of a Minneapolis police officer. Protests sweeping the United States over the death of George Floyd reverberated on the other side of the globe when thousands marched in solidarity on the streets of New Zealand

AFP via Getty

21/50 30 May 2020

Police officers are seen amid tear gas as protesters continue to rally against the death in Minneapolis police custody of George Floyd, in Minneapolis, Minnesota

Reuters

22/50 29 May 2020

A boy holds a sign as refugees protest outside the UNHCR offices against a government decision that they should leave their accommodation provided through European Union and UNHCR funds by the end of May, in Athens, Greece

Reuters

23/50 28 May 2020

Cloud iridescence, an optical phenomenon where light is diffracted through water droplets, is pictured at the edge of some clouds before a summer thunderstorm over Bangkok

AFP via Getty

24/50 27 May 2020

Riot police try to control pro-democracy supporters at a rally in Causeway Bay district, Hong Kong

Getty

25/50 26 May 2020

Protesters and police face each other during a rally after a black man died in police custody hours after a bystander’s video showed an officer kneeling on the handcuffed man’s neck, even after he pleaded that he could not breathe and had stopped moving

Star Tribune via AP

26/50 25 May 2020

The aerobatic demonstration team ‘Frecce Tricolori’ of the Italian Air Force flies in formation above the Milan Cathedral. Starting from 25 May, the Frecce Tricolori will perform every day in the skies throughout Italy as part of the 74th anniversary celebrations of the founding of the Italian Republic and to pay homage to the areas most affected by the coronavirus

EPA

27/50 24 May 2020

Saudi Arabia’s holy city of Mecca during the early hours of Eid al-Fitr, the Muslim holiday which starts at the conclusion of the holy fasting month of Ramadan

AFP via Getty

28/50 23 May 2020

Tamika Eastley, left, and Anthony Ragusa work out as the sun sets over the Kangaroo Point Cliffs in Brisbane, Australia

EPA

29/50 22 May 2020

Firefighters spray water on the wreckage of a Pakistan International Airlines aircraft after it crashed into a residential area in Karachi

AFP via Getty

30/50 21 May 2020

Indigenous leader Kretan Kaingang wears a face mask with a hashtag that reads in Portuguese: “Get out Bolsonaro” during a protest demanding the impeachment of President Jair Bolsonaro outside the National Congress in Brasilia, Brazil, Thursday, May 21, 2020. As Brazil careens toward a full-blown public health emergency and economic meltdown, opponents have filed a request for Bolsonaro’s impeachment based on his mishandling of the new coronavirus pandemic. (AP Photo/Eraldo Peres)

AP

31/50 20 May 2020

People wait in line to undergo the coronavirus tests while keeping distance from each other at a makeshift clinic set up on a playground in Incheon, South Korea

Yonhap/AP

32/50 19 May 2020

Firefighters fighting a fire at a plastics factory in front of a huge cloud of smoke in Ladenburg, Germany

dpa via AP

33/50 18 May 2020

Ugandan academic Stella Nyanzi reacts as police officers detain her for protesting against the way that government distributes the relief food and lockdown situation in Kampala

Reuters

34/50 17 May 2020

A woman sits alone on a bench in a park following the outbreak of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19), in Dublin, Ireland

Reuters

35/50 16 May 2020

Crematory workers using protective gear are pictured at a crematory in Nezahualcoyotl during the outbreak of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19), on the outskirts of Mexico City, Mexico

Reuters

36/50 15 May 2020

Healthcare workers, nurses and doctors, unified under the movement called “Take Care of Care” wearing face masks protest against the Belgian authorities’ management of the coronavirus crisis, at the MontLegia CHC Hospital

Reuters

37/50 14 May 2020

A girl watches over goats on the banks of the Dal Lake during rainfall in Srinagar

AFP via Getty Images

38/50 13 May 2020

Life-size cardboard figures with photos of football fans are positioned on the stands of Borussia Moenchengladbach’s football stadium for their next game, which will be played without spectators, due to the coronavirus outbreak in Germany

Reuters

39/50 12 May 2020

Nurses wearing face masks take part in an event held to mark International Nurses Day, at Wuhan Tongji Hospital in China

China Daily via Reuters

40/50 11 May 2020

Iraqi protesters gather on the Al-Jumhuriyah bridge in the capital Baghdad during an anti-government demonstration. Modest anti-government rallies resumed in some Iraqi cities Sunday, clashing with security forces and ending months of relative calm just days after Prime Minister Mustafa Kadhemi’s government came to power. The protests first erupted in Baghdad and Shiite-majority southern cities in October, demanding an end to corruption and unemployment and an overhaul of the ruling class

AFP via Getty

41/50 10 May 2020

A man wearing a mask walks his dog in Madrid during the hours allowed by the government to exercise. Spain’s two biggest cities, Madrid and Barcelona, will not enter the next phase out of coronavirus lockdown along with many other regions next week

AFP via Getty

42/50 9 May 2020

Russian President Vladimir Putin addresses the nation after laying flowers at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier near the Kremlin wall in Moscow, Russia. Russia marks the 75th anniversary since the capitulation of Nazi Germany in WWII amid the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic

EPA

43/50 8 May 2020

German Chancellor Angela Merkel, President of the German Parliament Bundestag Wolfgang Schaeuble, German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier, President of the Federal Council Bundesrat in Germany Dietmar Woidke and the presiding judge of the German Federal Constitutional Court’s second senate, Andreas Vosskuhle attend wreath-laying ceremony to mark the 75th anniversary of the end of World War Two, at the Neue Wache Memorial in Berlin. Countries in Europe are commemorating the Victory in Europe Day, known as VE Day that celebrates Nazi Germany’s surrender during World World II on 8 May 1945

EPA

44/50 7 May 2020

A policeman uses his baton to push a resident breaking rules, during an extended nationwide lockdown to slow down the spread of coronavirus in Ahmedabad, India

Reuters

45/50 6 May 2020

A nurse tends to a crying newborn baby wearing a face shield at the National Maternity Hospital in Hanoi

AFP via Getty

46/50 5 May 2020

Bride Janine runs over to her wedding at a Drive-in cinema in Duesseldorf, Germany. The Drive-in theatre started to register official marriages on a stage, allowing all relatives and friends to attend in their cars, as weddings at the registry office are limited due to the coronavirus pandemic

AP

47/50 4 May 2020

Storekeepers asking for the reopening of shops and commercial activities gather for a flashmob protest on Piazza San Marco in Venice, as Italy starts to ease its lockdown

AFP via Getty

48/50 3 May 2020

A street vendor wearing a protective face mask waits for customers in Chinatown, after the government started opening some restaurants outside shopping malls, parks, and barbershops in Bangkok, Thailand

Reuters

49/50 2 May 2020

Two women carry longboards on an esplanade in Barcelona, during the hours allowed by the government to exercise, for the first time since the beginning of a national lockdown. All Spaniards are again allowed to leave their homes since today to walk or play sports after 48 days of very strict confinement to curb the coronavirus pandemic

AFP via Getty

50/50 1 May 2020

A girl, wearing a protective mask, plays with bubbles at a shopping mall in Gimpo, South Korea

Reuters

All the demographic factors that are supposed to be against Labour now were for it then. Its voters were more middle-class than ever; it won Canterbury and Kensington; and yet the party held the working-class red wall seats.

All that had changed by 2019. To be fair, the report does say that by then Corbyn was irrecoverably unpopular, facing both ways on Brexit and making incredible spending promises. But what it does not say is that he supported Jo Swinson in making the biggest mistake of all, which was to allow the election to happen in the first place.

The events of 25-28 October last year remain one of the great mysteries of modern British politics. Swinson’s decision that weekend to back an early election was pivotal, but Nicola Sturgeon, who appeared to be in favour of it before she was against it, and Corbyn, who was against it before he was for it, played their supporting roles.

What will decide the next election will not be some pseudo-sociology about class dealignment or changing culture. It will be politics. Will the Conservatives be ruthless enough to get Boris Johnson out and put Rishi Sunak in? Will they look like an incompetent shower who handled coronavirus and the ensuing recession badly? Will Starmer inspire confidence that he would do a better job?

The new Labour leader has certainly made a good start. More significant than any retrospective analysis was the news this week that three Jewish peers, David Triesman, Parry Mitchell and Leslie Turnberg, have rejoined the party.

If the politics is right, the demography will take care of itself. We had all that nonsense about social change eroding Labour’s support in the 1950s, because the working classes were buying fridges. We had it again in the 1980s, because they were buying their own homes. Now we are having it a third time because the Tories are giving them Brexit and 50,000 more nurses for the NHS.

There is nothing inevitable about any of it. Labour can win, but it has to get the politics right.