A few weeks ago, the outspoken Labour MP Jess Phillips, at the time a leadership candidate, was asked by Andrew Marr about the possibility of Britain rejoining the European Union in a few years’ time. She said this: “You would have to look at what is going on at the time … so if we are living in an absolute paradise of trade, and we’re totally safe in the world, and we’re not going to worry about having to constantly look to America for our safety and security, then maybe I’ll be proven wrong. But the reality is that if our country is safer, if it more economically viable to be in the EU, then I will fight for that, regardless of how difficult that argument is to make.”

Not long after, lacking some support across the party, Phillips withdrew from the race, and the other candidates seem disinclined to spend much time considering re-entry while the country was still technically a member of the EU, and after all the traumas of the past few years. British re-entry, which we might dub “Bre-entry”, will not replace Brexit as a national obsession for some time, if ever.

Still, the European issue is not going to go away, and the debate about Britain’s relationship with the rest of the continent is not going to suddenly disappear entirely. It has been around in its current form since the end of the Second World War, and in other iterations for many centuries before that, all the way past Hitler, the Kaiser, Napoleon, the Spanish Armada, Henry VIII’s break with Rome, the Norman Conquest, the Anglo Saxons, Viking incursions all the way back to the Romans. As Boris Johnson once said, Brexit does not mean Britain is about to be towed out into the Atlantic (much as some might like it).

Download the new Independent Premium app

Sharing the full story, not just the headlines

In fact there are perfectly plausible cases to be made for Bre-entry being inevitable; and for it being inconceivable. As Phillips indicated, it all depends.

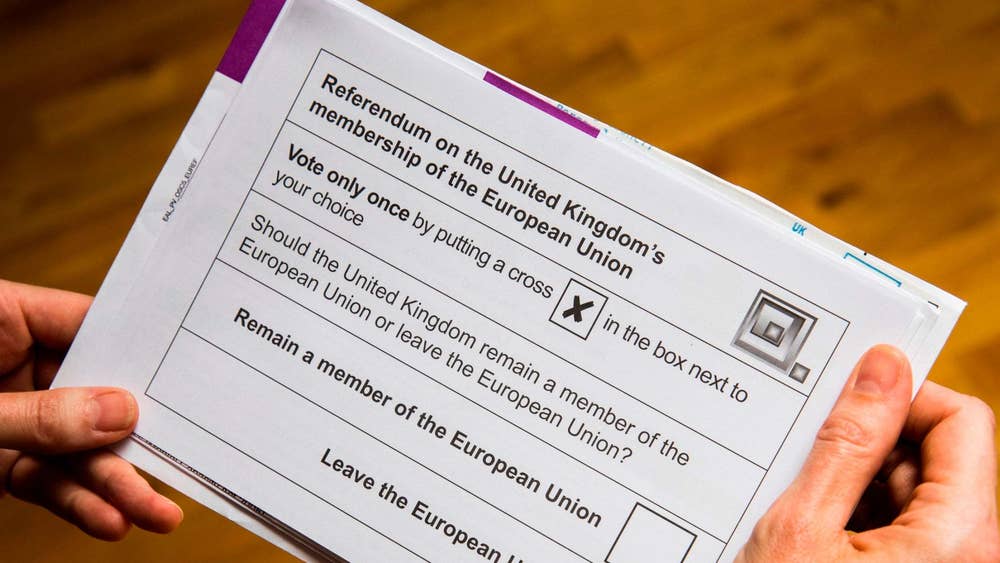

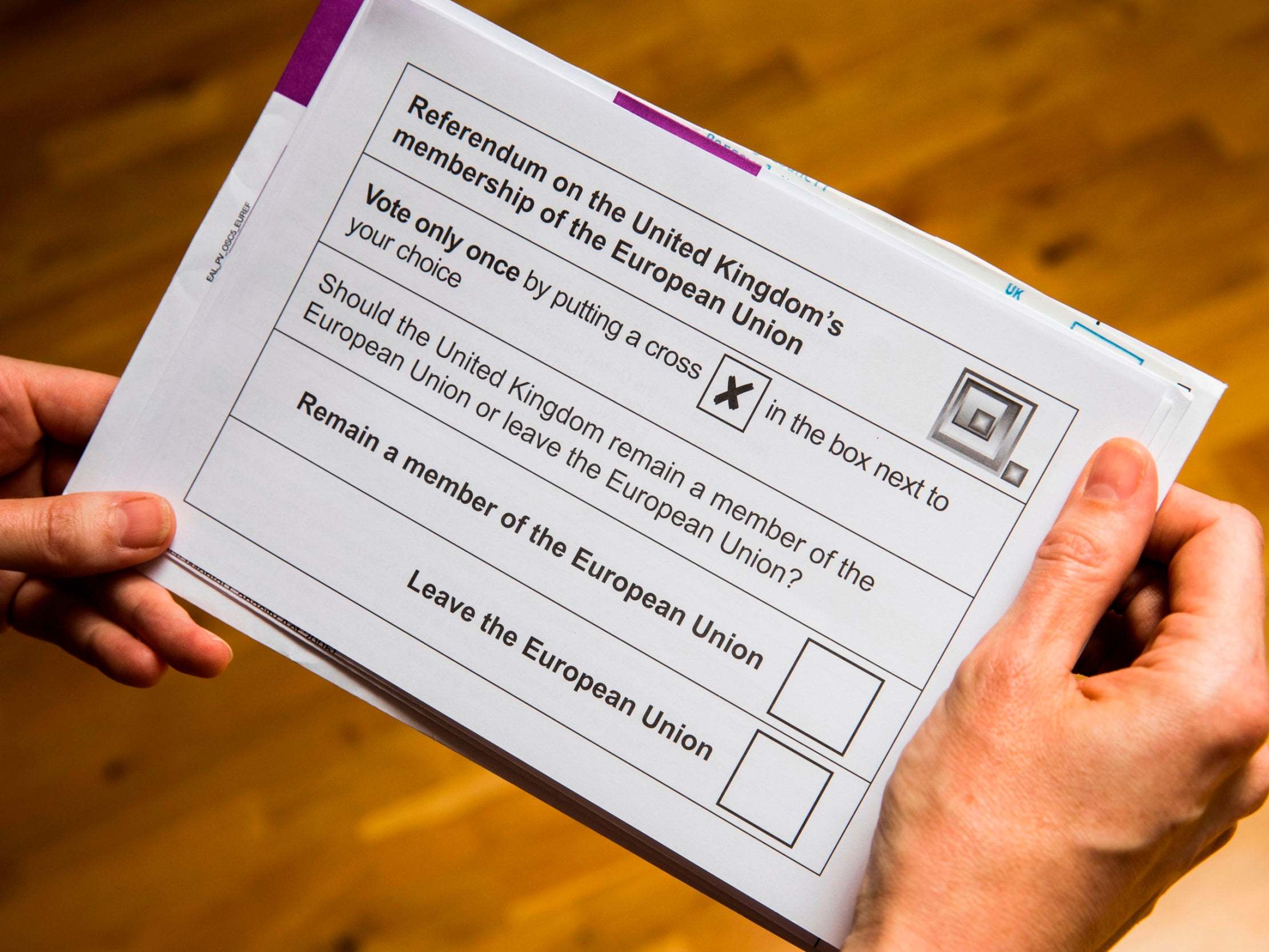

1/20 Britain votes to leave the European Union – 23 June 2016

A referendum is held on Britain’s membership of the European Union. Fifty-two per cent of the country votes in favour of leaving

AFP via Getty

2/20 David Cameron resigns – 24 June 2016

David Cameron resigns on the morning of the result after leading the campaign for Britain to remain in the EU

Getty

3/20 Theresa May takes the reins – 13 July 2016

Theresa May becomes leader of the Conservative party and prime minister, winning the leadership contest unopposed after Andrea Leadsom drops out

Getty

4/20 High Court rules parliament must vote on Brexit – November 2016 – 3 November 2016

The High Court rules that parliament must vote on triggering Article 50, which would begin the Brexit process

5/20 Article 50 triggered – 28 March 2017

The prime minister triggers Article 50 after parliament endorses the result of the referendum

Getty

6/20 May calls snap election – 18 April 2018

Seeking a mandate for her Brexit plan, May goes to the country

Getty

7/20 May loses majority as Labour makes surprise gain – 8 June 2017

After a disastrous campaign, Theresa May loses her majority in the commons and turns to the DUP for support. Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour party makes gains after being predicted to lose heavily

AFP/Getty

8/20 Negotiations begin – 19 June 2017

David Davis and Michel Barnier, chief negotiators for the UK and EU respectively, hold a press conference on the first day of Brexit negotiations. Soon after the beginning of negotiations, it becomes clear that the issue of the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic will prove a major sticking point

AFP/Getty

9/20 MPs vote that withdrawal deal must be ratified by parliament – 13 December 2017

The government suffers a defeat in parliament over the EU withdrawal agreement, guaranteeing that MPs are given a ‘meaningful vote’ on the deal

10/20 Boris Johnson resigns as foreign secretary – 11 July 2018

Following a summit at Chequers where the prime minister claimed to have gained cabinet support for her deal, Boris Johnson resigns as foreign secretary along with David Davis, the Brexit secretary

Reuters

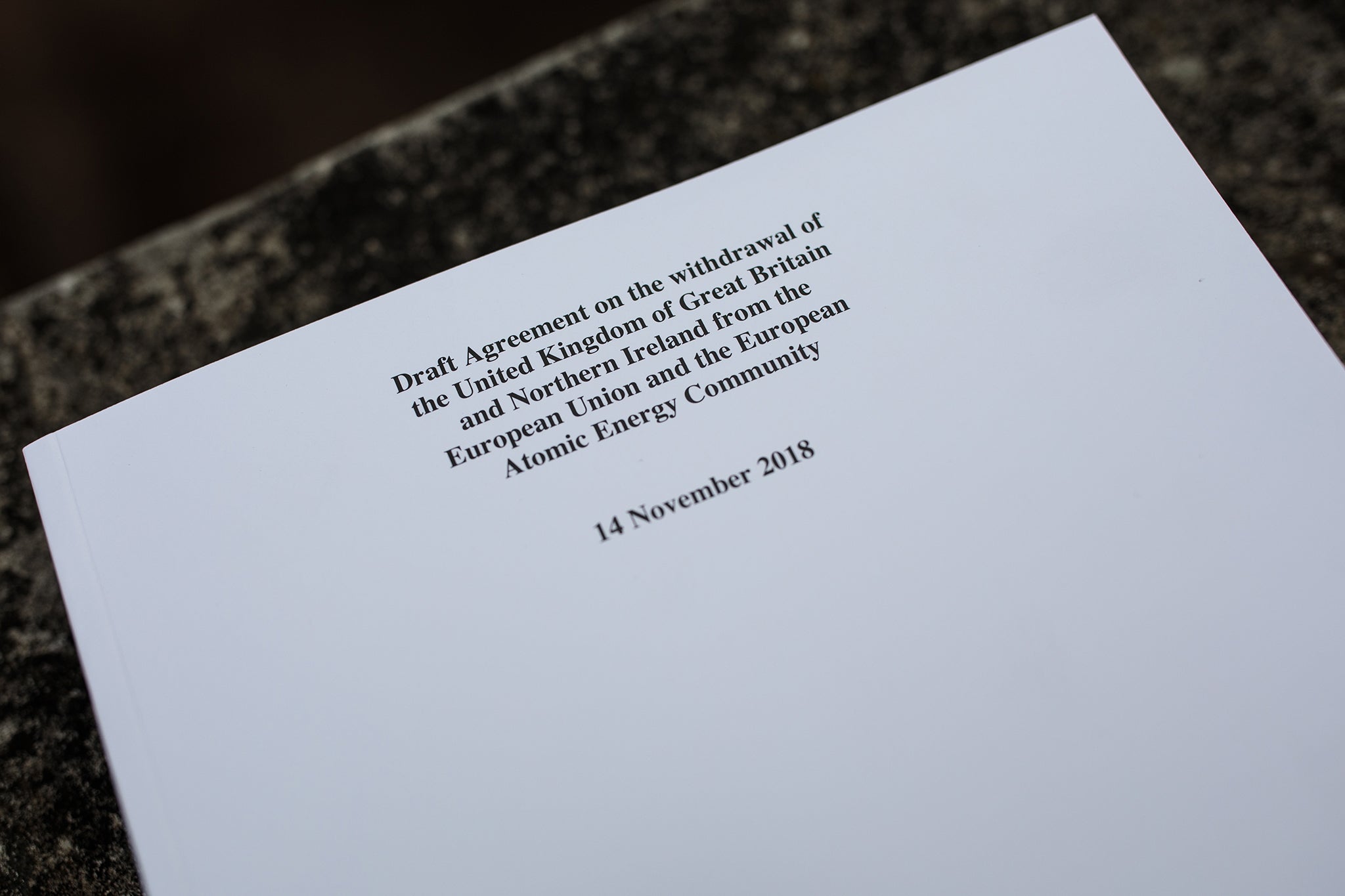

11/20 Draft withdrawal agreement – 15 November 2018

The draft withdrawal agreement settles Britain’s divorce bill, secures the rights of EU citizens living in the UK and vice versa and includes a political declaration commiting both parties to frictionless trade in goods and cooperation on security matters. The deal also includes the backstop, which is anathema to many brexiteers and Dominic Raab and Esther McVey resign from the cabinet in protest

Getty

12/20 May resigns – 24 May 2019

After several failed attempts to pass her withdrawal agreement through the commons, Theresa May resigns

Reuters

13/20 Johnson takes over – 24 July 2019

Boris Johnson is elected leader of the Conservative party in a landslide victory. He later heads to Buckingham Palace where the Queen invites him to form a government

Getty

14/20 Parliament prorogued – 28 August 2019

Boris Johnson prorogues parliament for five weeks in the lead up to the UK’s agreed departure date of 31 October.

Stephen Morgan MP

15/20 Prorogation ruled unlawful – 24 September 2019

The High Court rules that Johnson’s prorogation of parliament is ‘unlawful’ after a legal challenge brought by businesswoman Gina Miller

Getty

16/20 Johnson agrees deal with Varadkar – October

Following a summit in Merseyside, Johnson agrees a compromise to the backstop with Irish prime minister Leo Varadkar – making the withdrawal agreement more palatable to Brexiteers

Getty

17/20 Final Say march demands second referendum – 19 October 2019

As parliament passes the Letwin amendment requiring the prime minister to request a further delay to Brexit, protesters take to the streets in the final show of force for a Final Say referendum

Getty

18/20 Johnson wins 80 seat majority – 12 December 2019

The Conservatives win the December election in a landslide, granting Boris Johnson a large majority to pass through his brexit deal and pursue his domestic agenda

Getty

19/20 Withdrawal deal passes parliament – 20 December 2019

The withdrawal agreement passes through the commons with a majority of 124

Getty

20/20 EU parliament backs UK withdrawal deal – 29 January 2020

Members of the European parliament overwhelmingly back the ratification of Britain’s departure, clearing the way for Brexit two days later on 31 January. Following the vote, members join hands and sing Auld Lang Syne

AFP/Getty

1/20 Britain votes to leave the European Union – 23 June 2016

A referendum is held on Britain’s membership of the European Union. Fifty-two per cent of the country votes in favour of leaving

AFP via Getty

2/20 David Cameron resigns – 24 June 2016

David Cameron resigns on the morning of the result after leading the campaign for Britain to remain in the EU

Getty

3/20 Theresa May takes the reins – 13 July 2016

Theresa May becomes leader of the Conservative party and prime minister, winning the leadership contest unopposed after Andrea Leadsom drops out

Getty

4/20 High Court rules parliament must vote on Brexit – November 2016 – 3 November 2016

The High Court rules that parliament must vote on triggering Article 50, which would begin the Brexit process

5/20 Article 50 triggered – 28 March 2017

The prime minister triggers Article 50 after parliament endorses the result of the referendum

Getty

6/20 May calls snap election – 18 April 2018

Seeking a mandate for her Brexit plan, May goes to the country

Getty

7/20 May loses majority as Labour makes surprise gain – 8 June 2017

After a disastrous campaign, Theresa May loses her majority in the commons and turns to the DUP for support. Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour party makes gains after being predicted to lose heavily

AFP/Getty

8/20 Negotiations begin – 19 June 2017

David Davis and Michel Barnier, chief negotiators for the UK and EU respectively, hold a press conference on the first day of Brexit negotiations. Soon after the beginning of negotiations, it becomes clear that the issue of the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic will prove a major sticking point

AFP/Getty

9/20 MPs vote that withdrawal deal must be ratified by parliament – 13 December 2017

The government suffers a defeat in parliament over the EU withdrawal agreement, guaranteeing that MPs are given a ‘meaningful vote’ on the deal

10/20 Boris Johnson resigns as foreign secretary – 11 July 2018

Following a summit at Chequers where the prime minister claimed to have gained cabinet support for her deal, Boris Johnson resigns as foreign secretary along with David Davis, the Brexit secretary

Reuters

11/20 Draft withdrawal agreement – 15 November 2018

The draft withdrawal agreement settles Britain’s divorce bill, secures the rights of EU citizens living in the UK and vice versa and includes a political declaration commiting both parties to frictionless trade in goods and cooperation on security matters. The deal also includes the backstop, which is anathema to many brexiteers and Dominic Raab and Esther McVey resign from the cabinet in protest

Getty

12/20 May resigns – 24 May 2019

After several failed attempts to pass her withdrawal agreement through the commons, Theresa May resigns

Reuters

13/20 Johnson takes over – 24 July 2019

Boris Johnson is elected leader of the Conservative party in a landslide victory. He later heads to Buckingham Palace where the Queen invites him to form a government

Getty

14/20 Parliament prorogued – 28 August 2019

Boris Johnson prorogues parliament for five weeks in the lead up to the UK’s agreed departure date of 31 October.

Stephen Morgan MP

15/20 Prorogation ruled unlawful – 24 September 2019

The High Court rules that Johnson’s prorogation of parliament is ‘unlawful’ after a legal challenge brought by businesswoman Gina Miller

Getty

16/20 Johnson agrees deal with Varadkar – October

Following a summit in Merseyside, Johnson agrees a compromise to the backstop with Irish prime minister Leo Varadkar – making the withdrawal agreement more palatable to Brexiteers

Getty

17/20 Final Say march demands second referendum – 19 October 2019

As parliament passes the Letwin amendment requiring the prime minister to request a further delay to Brexit, protesters take to the streets in the final show of force for a Final Say referendum

Getty

18/20 Johnson wins 80 seat majority – 12 December 2019

The Conservatives win the December election in a landslide, granting Boris Johnson a large majority to pass through his brexit deal and pursue his domestic agenda

Getty

19/20 Withdrawal deal passes parliament – 20 December 2019

The withdrawal agreement passes through the commons with a majority of 124

Getty

20/20 EU parliament backs UK withdrawal deal – 29 January 2020

Members of the European parliament overwhelmingly back the ratification of Britain’s departure, clearing the way for Brexit two days later on 31 January. Following the vote, members join hands and sing Auld Lang Syne

AFP/Getty

The case for inevitability is primarily an economic and trading one. In an extreme scenario, it is possible that the UK will have failed to secure any meaningful free trade deals with the EU or with America, let alone China and India, by the time of a general election in 2024 or 2029. Indeed it is also possible that the British could find themselves embroiled in low-level trade wars with both the EU and the US, with matters such as citizens’ rights, fishing, extradition, or Chinese access to UK 5G infrastructure complicating the already complex talks. There are obvious signs of such diplomatic tensions simmering already.

For a medium-sized but very open economy dependent on trade and investment for its prosperity, such a turn of events would imply a catastrophic loss of markets and inward investment, depressing growth and employment – and thus living standards and public services. Britain, in effect, would be forced into abandoning its great Brexit adventure and begging the EU to let it back in, on whatever terms could be agreed. They would not be as advantageous as now; nor as yummy as multiple free trade deals across all the biggest and fastest growing economies in the world; but much better than having to survive without frictionless access to our closest neighbours.

Thus if the promised economic advantages of Brexit fail to materialise, and the economy stagnates, there will be seen to have been little advantage gained by “taking back control”. As in the 1970s, Britain would be the “sick man of Europe”; a sclerotic nation with its citizens fighting like rats in a sack over what little money is around – an even more divided and unequal society than today. Indeed such unhappy economic times would be exacerbated if there was a more generalised world downturn (which Brexit could not be blamed for, but would nonetheless be linked). Again, given trade wars and geopolitical uncertainties in the Middle East, this is a quite realistic possible outcome of current trends.

By the same token it is perfectly conceivable, indeed more conceivable, that the housing crisis, the care crisis and the illegal migration crisis will show no signs of abating. If the 2016 referendum and Brexit was won partly in the immigration issue, it might be lost again (though illogically) if Brexit fails to result in managed migration. After all, that is the record on non-EU migration over the past decade or more.

The pressures on the union from Scottish separatism and Irish nationalism could turn quite ugly, and be impossible for Westminster to resist, without, that is, reversing Brexit. There would be some tough choices to make; a rump state of England and Wales outside the EU, or the present UK back inside it?

Lastly, Europe itself might conceivably evolve, in a direction that would make it easier for the UK to join with some dignity.

The latest news on Brexit, politics and beyond direct to your inbox

Naturally Brexit has been discussed in a totally British-centred, if not Anglocentric, way. Little attention has been paid to what it will do to the balance of power within the continuing bloc of 27 nations. The working assumption must be that it will strengthen the position of the European integrationists. With Angela Merkel retiring soon, France seems destined again to assume a leadership role in Europe. President Macron believes the answer to the European Union’s problems is “more Europe”. This means a fiscal union and banking union to match the monetary union and single currency.

Yet that is something that nations such as Sweden, the Netherlands, Finland and Germany, as richer, more solvent nations, will never find acceptable. Put bluntly, it means putting their taxpayers in a permanent obligation to rescue bankrupt nations and banks south of the Alps. Meantime the rise of the nationalists in Italy, Poland and Hungary, driven by hostility to Brussels and failures in immigration, means the EU project is unpopular even in places where it has been of huge net economic benefit.

It is not unthinkable that the EU would become less a political union and more the kind of Europe of nation states the British always preferred. That is to say, no more unthinkable than to see a bunch of anti-EU German nationalists effectively become the official opposition in the Bundestag, or fascistic parties in or close to government in the Netherlands, Italy or Austria.

A new looser EU, dropping free movement of labour, restoring national vetoes and liberalising its markets to the wider world, might well be one the British would love to be part of.

Yet that might not happen, and the same centripetal forces that have exerted themselves so relentlessly will continue undisturbed by public disquiet, as they have since the Treaty of Rome set up the EU in 1957. The absence of the British will indeed strengthen them. If so, then it would make Bre-entry far less likely.

Thus, if the UK had to accept a commitment to join the euro as the price of membership, even the most Europhile might have second thoughts. For the euro, itself an inflexible economic discipline, is a mere portal into a world of EU-run tax and public spending and borrowing controls – a quantum leap in loss of sovereignty and control. It has certainly something few in either main party could advocate. On top of that, Britain might also have to sacrifice its old EU budget rebate and agree to submit UK budgets to the EU Commission. That’s assuming, of course, that the French don’t veto a British application again, as they saw fit to twice in the 1960s.

Besides – the economic disaster might not happen. If global growth picks up, then it might offset some of the damage from Brexit. If Donald Trump survives in office and grants the UK the sort of amazing deal he brags about, well that would help too, especially if the new talks with Michel Barnier go well. The UK could swiftly hitch itself to fast-growing China, India and other Asian and African markets.

Of course, any economist can argue, with some force, that any outcome will be worse than if we had stayed inside the EU; but that is an improvable, parallel-universe sort of case that the voters may not have much time for. No one will be able to point to the absent factories and office blocks that would have been built in a hypothetical scenario. The UK might just bumble along growing at 1.5 per cent a year. It would be uncomfortable, and far lower than the averages in the 1990s and 2000s; but maybe better or around the past decade or in the 1970s.

One oddity of Brexit might be that a sudden restriction on immigration in an already tight labour market would give a short-term boost to wage rates. If so it will be seized on by the Brexiteers that they were right all along (even if that rise in labour costs pushes firms out of business and means more machines, computers and AI replace more expensive humans in workplaces).

That leads us to the “poor but happy” argument. During the great Brexit debate there arose one of many urban legends – the Leave voter who declared they’d still vote Leave even if it meant they’d lose their own job. For them the idea that they’d be £400 a year better off (or whatever) in some parallel would where we’d stayed in the EU is for the birds. Like it or not they will applaud lower immigration (if it can be achieved) and the restoration of political sovereignty. For that section of the population, as in 2016 and after, economic arguments are less relevant than an emotional appeal to retain control, and not lose it again to Brussels.

It is also difficult to imagine the British embracing another great debate on Europe, tearing up new EU and US trade deals just as soon as they are signed, just so we can go through the whole thing again in reverse. After the 1975 and 2016 referendums set the precedents, it is hard to see the electorate contemplating returning to the EU without popular consent. The question would be what the terms would be; and how would we know that the terms agreed might evolve uncontrollably so they are unrecognisable (as arguably happened after the UK joined a “common market” with national vetoes in 1973). It would be a Brenda from Bristol moment – “not another one”.

And if Britain would be in poor shape by the mid-2020s, who’s to say the EU might be in even greater difficulties?

1/2

GETTY IMAGES

2/2

EPA

1/2

GETTY IMAGES

2/2

EPA

All the economic and financial stresses induced by the euro on weaker banks and economies are still there, and the migrant crisis might easily flare up again. Those TV images, of Greek riots, of nutty extremists winning elections and pitiful refugees trying and sometimes dying crossing the Mediterranean, were powerful factors in reinforcing negative British opinions about the EU in the years before the 2016 referendum. It is often thought that the rising generation – overwhelming Remainers – will one day come to reverse Brexit, as their more Eurosceptic parents and grandparents fall off the electoral registers, to put it sensitively.

Psephological expert Peter Kellner has said that demographic change (euphemism) means that the 2016 result would be reversed even now, under certain assumptions. Yet the young Europhile idealists of today are only the older, more cynical voters of tomorrow. Above all they will, as Philips says, have a very good hard look at what is happening at the time. “Bre-entry” for the mostly pragmatic British, is neither inevitable nor inconceivable.