For many Britons living in towns and villages across Europe, the arrival of Brexit on Friday night will mean losing the right to vote and stand for office.

From being active participants in the communities where they have spread roots and paid taxes, British expatriates in France, Germany and elsewhere in the European Union will suddenly find themselves on the outside with no say.

Andrew Nixey must give up his seat on the elected council in Saint-Martial-sur-Isop, the village in west-central France where he has lived and raised cattle for 20 years.

Download the new Independent Premium app

Sharing the full story, not just the headlines

He said: “The fact that we can’t vote is illogical.

“We pay taxes, why should we not vote?”

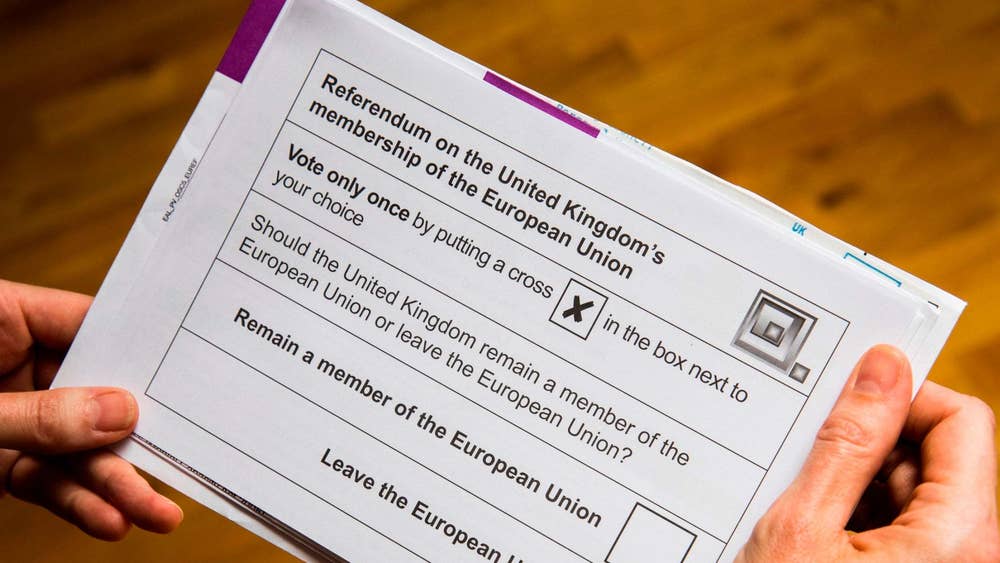

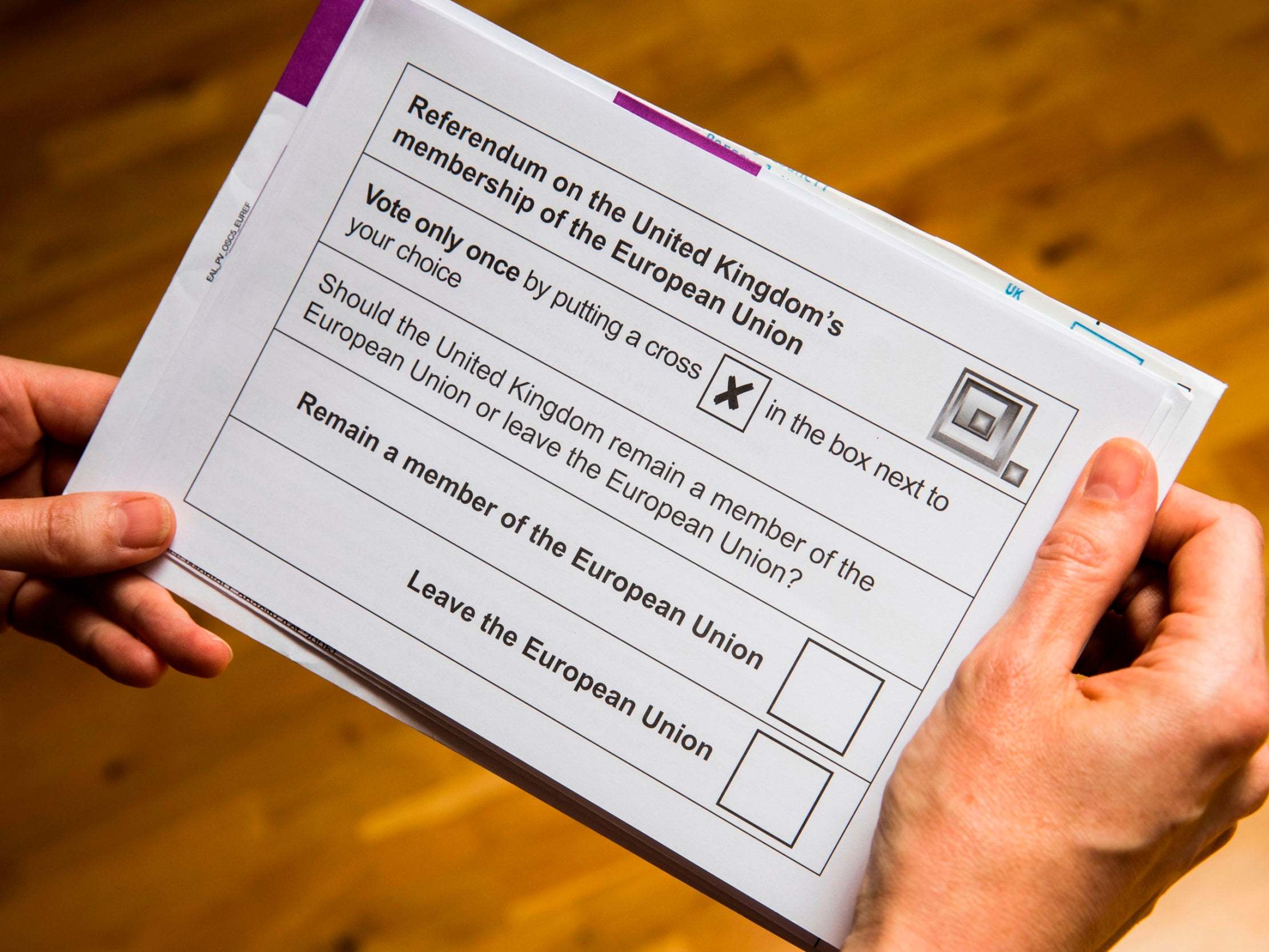

1/20 Britain votes to leave the European Union – 23 June 2016

A referendum is held on Britain’s membership of the European Union. Fifty-two per cent of the country votes in favour of leaving

AFP via Getty

2/20 David Cameron resigns – 24 June 2016

David Cameron resigns on the morning of the result after leading the campaign for Britain to remain in the EU

Getty

3/20 Theresa May takes the reins – 13 July 2016

Theresa May becomes leader of the Conservative party and prime minister, winning the leadership contest unopposed after Andrea Leadsom drops out

Getty

4/20 High Court rules parliament must vote on Brexit – November 2016 – 3 November 2016

The High Court rules that parliament must vote on triggering Article 50, which would begin the Brexit process

5/20 Article 50 triggered – 28 March 2017

The prime minister triggers Article 50 after parliament endorses the result of the referendum

Getty

6/20 May calls snap election – 18 April 2018

Seeking a mandate for her Brexit plan, May goes to the country

Getty

7/20 May loses majority as Labour makes surprise gain – 8 June 2017

After a disastrous campaign, Theresa May loses her majority in the commons and turns to the DUP for support. Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour party makes gains after being predicted to lose heavily

AFP/Getty

8/20 Negotiations begin – 19 June 2017

David Davis and Michel Barnier, chief negotiators for the UK and EU respectively, hold a press conference on the first day of Brexit negotiations. Soon after the beginning of negotiations, it becomes clear that the issue of the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic will prove a major sticking point

AFP/Getty

9/20 MPs vote that withdrawal deal must be ratified by parliament – 13 December 2017

The government suffers a defeat in parliament over the EU withdrawal agreement, guaranteeing that MPs are given a ‘meaningful vote’ on the deal

10/20 Boris Johnson resigns as foreign secretary – 11 July 2018

Following a summit at Chequers where the prime minister claimed to have gained cabinet support for her deal, Boris Johnson resigns as foreign secretary along with David Davis, the Brexit secretary

Reuters

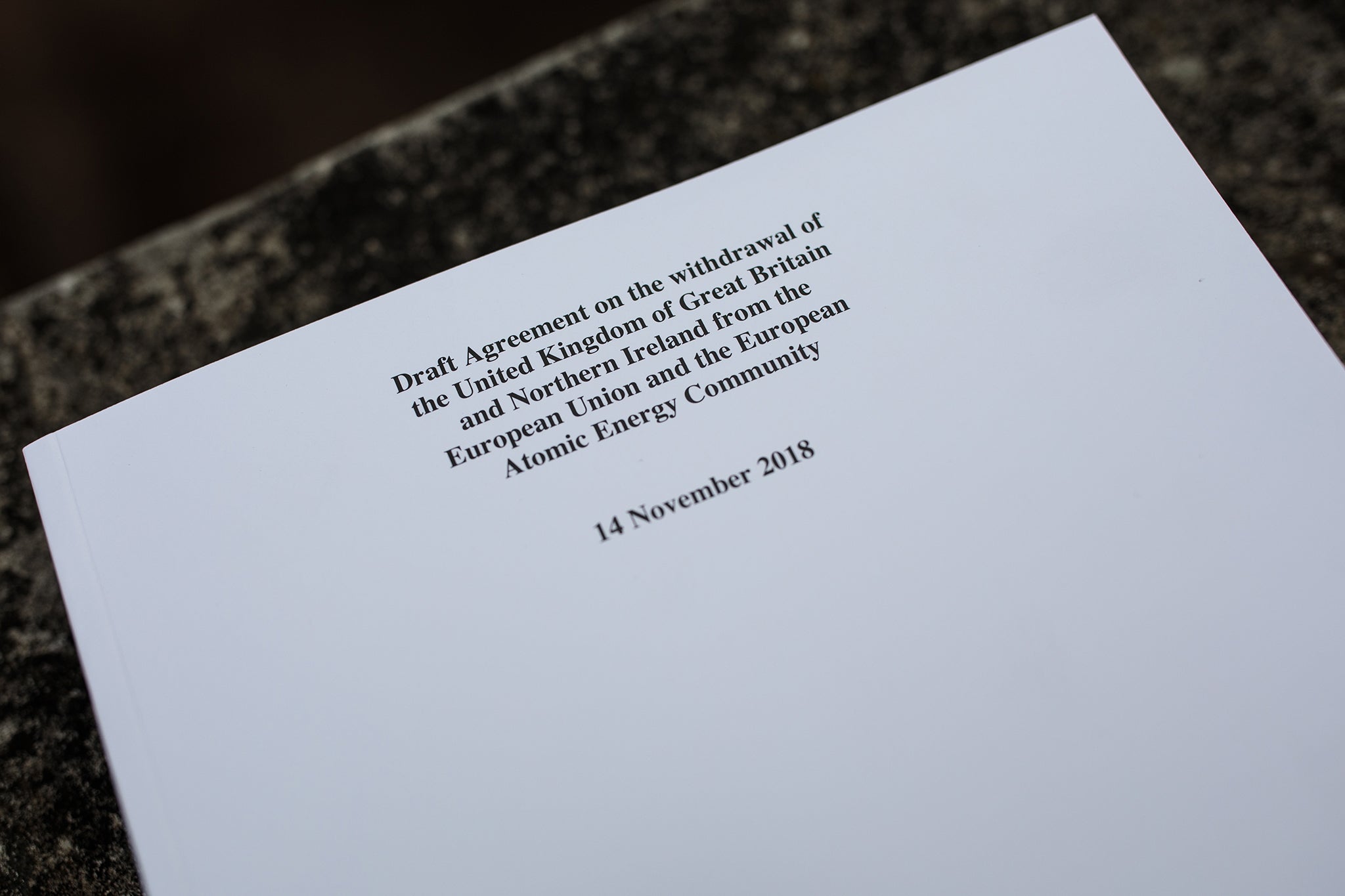

11/20 Draft withdrawal agreement – 15 November 2018

The draft withdrawal agreement settles Britain’s divorce bill, secures the rights of EU citizens living in the UK and vice versa and includes a political declaration commiting both parties to frictionless trade in goods and cooperation on security matters. The deal also includes the backstop, which is anathema to many brexiteers and Dominic Raab and Esther McVey resign from the cabinet in protest

Getty

12/20 May resigns – 24 May 2019

After several failed attempts to pass her withdrawal agreement through the commons, Theresa May resigns

Reuters

13/20 Johnson takes over – 24 July 2019

Boris Johnson is elected leader of the Conservative party in a landslide victory. He later heads to Buckingham Palace where the Queen invites him to form a government

Getty

14/20 Parliament prorogued – 28 August 2019

Boris Johnson prorogues parliament for five weeks in the lead up to the UK’s agreed departure date of 31 October.

Stephen Morgan MP

15/20 Prorogation ruled unlawful – 24 September 2019

The High Court rules that Johnson’s prorogation of parliament is ‘unlawful’ after a legal challenge brought by businesswoman Gina Miller

Getty

16/20 Johnson agrees deal with Varadkar – October

Following a summit in Merseyside, Johnson agrees a compromise to the backstop with Irish prime minister Leo Varadkar – making the withdrawal agreement more palatable to Brexiteers

Getty

17/20 Final Say march demands second referendum – 19 October 2019

As parliament passes the Letwin amendment requiring the prime minister to request a further delay to Brexit, protesters take to the streets in the final show of force for a Final Say referendum

Getty

18/20 Johnson wins 80 seat majority – 12 December 2019

The Conservatives win the December election in a landslide, granting Boris Johnson a large majority to pass through his brexit deal and pursue his domestic agenda

Getty

19/20 Withdrawal deal passes parliament – 20 December 2019

The withdrawal agreement passes through the commons with a majority of 124

Getty

20/20 EU parliament backs UK withdrawal deal – 29 January 2020

Members of the European parliament overwhelmingly back the ratification of Britain’s departure, clearing the way for Brexit two days later on 31 January. Following the vote, members join hands and sing Auld Lang Syne

AFP/Getty

1/20 Britain votes to leave the European Union – 23 June 2016

A referendum is held on Britain’s membership of the European Union. Fifty-two per cent of the country votes in favour of leaving

AFP via Getty

2/20 David Cameron resigns – 24 June 2016

David Cameron resigns on the morning of the result after leading the campaign for Britain to remain in the EU

Getty

3/20 Theresa May takes the reins – 13 July 2016

Theresa May becomes leader of the Conservative party and prime minister, winning the leadership contest unopposed after Andrea Leadsom drops out

Getty

4/20 High Court rules parliament must vote on Brexit – November 2016 – 3 November 2016

The High Court rules that parliament must vote on triggering Article 50, which would begin the Brexit process

5/20 Article 50 triggered – 28 March 2017

The prime minister triggers Article 50 after parliament endorses the result of the referendum

Getty

6/20 May calls snap election – 18 April 2018

Seeking a mandate for her Brexit plan, May goes to the country

Getty

7/20 May loses majority as Labour makes surprise gain – 8 June 2017

After a disastrous campaign, Theresa May loses her majority in the commons and turns to the DUP for support. Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour party makes gains after being predicted to lose heavily

AFP/Getty

8/20 Negotiations begin – 19 June 2017

David Davis and Michel Barnier, chief negotiators for the UK and EU respectively, hold a press conference on the first day of Brexit negotiations. Soon after the beginning of negotiations, it becomes clear that the issue of the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic will prove a major sticking point

AFP/Getty

9/20 MPs vote that withdrawal deal must be ratified by parliament – 13 December 2017

The government suffers a defeat in parliament over the EU withdrawal agreement, guaranteeing that MPs are given a ‘meaningful vote’ on the deal

10/20 Boris Johnson resigns as foreign secretary – 11 July 2018

Following a summit at Chequers where the prime minister claimed to have gained cabinet support for her deal, Boris Johnson resigns as foreign secretary along with David Davis, the Brexit secretary

Reuters

11/20 Draft withdrawal agreement – 15 November 2018

The draft withdrawal agreement settles Britain’s divorce bill, secures the rights of EU citizens living in the UK and vice versa and includes a political declaration commiting both parties to frictionless trade in goods and cooperation on security matters. The deal also includes the backstop, which is anathema to many brexiteers and Dominic Raab and Esther McVey resign from the cabinet in protest

Getty

12/20 May resigns – 24 May 2019

After several failed attempts to pass her withdrawal agreement through the commons, Theresa May resigns

Reuters

13/20 Johnson takes over – 24 July 2019

Boris Johnson is elected leader of the Conservative party in a landslide victory. He later heads to Buckingham Palace where the Queen invites him to form a government

Getty

14/20 Parliament prorogued – 28 August 2019

Boris Johnson prorogues parliament for five weeks in the lead up to the UK’s agreed departure date of 31 October.

Stephen Morgan MP

15/20 Prorogation ruled unlawful – 24 September 2019

The High Court rules that Johnson’s prorogation of parliament is ‘unlawful’ after a legal challenge brought by businesswoman Gina Miller

Getty

16/20 Johnson agrees deal with Varadkar – October

Following a summit in Merseyside, Johnson agrees a compromise to the backstop with Irish prime minister Leo Varadkar – making the withdrawal agreement more palatable to Brexiteers

Getty

17/20 Final Say march demands second referendum – 19 October 2019

As parliament passes the Letwin amendment requiring the prime minister to request a further delay to Brexit, protesters take to the streets in the final show of force for a Final Say referendum

Getty

18/20 Johnson wins 80 seat majority – 12 December 2019

The Conservatives win the December election in a landslide, granting Boris Johnson a large majority to pass through his brexit deal and pursue his domestic agenda

Getty

19/20 Withdrawal deal passes parliament – 20 December 2019

The withdrawal agreement passes through the commons with a majority of 124

Getty

20/20 EU parliament backs UK withdrawal deal – 29 January 2020

Members of the European parliament overwhelmingly back the ratification of Britain’s departure, clearing the way for Brexit two days later on 31 January. Following the vote, members join hands and sing Auld Lang Syne

AFP/Getty

In the German village of Brunsmark, Brexit is forcing Scotsman Iain Macnab to cut short his third term as mayor which was not due to end until 2023.

German authorities told him last year that his voting rights and his mayorship of the village of 170 people must end with Britain’s EU withdrawal.

Mr Macnab said: “The guillotine is there.

“I will have a glass of sparkling wine with the local council on Friday and then thank them for doing an excellent job, and I will disappear into the twilight, ride off into the sunset.”

Many details of Britain’s separation from the EU still must be sorted out, and there will not be many visible changes on Saturday, after the tortuous divorce process finally becomes official.

However, the loss will be felt by Britons who left years ago to make new lives on the continent.

Already disenfranchised by British electoral law, which prevents expatriates from voting in the United Kingdom after 15 years overseas, Brexit will for many usher in an uncertain future with no ability to vote anywhere.

The problem could be fixed by becoming citizens of where they have chosen to live – which can be a drawn-out process.

However, some expatriates do not meet the requirements, some have applied but are still awaiting the paperwork, and some simply do not want to change citizenship. Others have not got round to it, waking up late to the fact that they will soon have nowhere to vote at all.

Only the best news in your inbox

Mr Macnab said he does not want to be a German citizen, despite having lived in Germany for 40 years, because he may choose to move back to the UK some day.

“I have been 70 years a Scot,” he said.

“I don’t want to ruin the chance of going back to Britain and being covered by the National Health Service.”

The right for all EU nationals to vote and stand in municipal elections where they live, even if they are not citizens of that country, was enshrined in the 1992 Maastricht Treaty which established the EU.

However, rules in Europe are not uniform for non-EU citizens, which is what Britons will become after Friday night. Some countries allow non-EU citizens to vote in municipal elections. So even after Brexit, Britons should still have a voice at the local level in Denmark, Finland, Sweden, the Netherlands and in two cities in Slovakia. In Finland, they will need to have been residents for two years, while the residency requirement is five years in the Netherlands.

Britain also has been negotiating directly with other EU nations to extend the ability of British expatriates to vote and run for office after Brexit. The UK Government said it has deals with Spain, Portugal and Luxembourg and is continuing talks with other administrations. It said British expatriates should also still be able to vote locally in Belgium, Estonia, Ireland, Lithuania, Malta and Slovenia. But they will no longer be able to vote or stand locally in France, which has tens of thousands of long-term British residents and many more part-time residents of holiday homes.

The French interior ministry said 757 Britons serve on municipal councils, more than any other expatriate group. They will keep their seats until municipal elections in March, but they will not be able to run or vote then if they have not gained French citizenship.

For Elaine Bastian, this has come as a blow. She has been proud to serve as an elected councillor since 2014 in the village of Blond, which has 700 residents and boasts a fortified medieval church.

She said: “I do feel robbed, almost, of my little crown, my hat of responsibility.

“It makes me angry more than anything. I really don’t like other people being able to make my life choices. It was my life choice to be a councillor.”

Mr Nixey said his application for French citizenship is stuck somewhere in a Brexit-induced backlog. He is not optimistic that he will get it in time to stand again for re-election in Saint-Martial-sur-Isop.

Mr Nixey said that serving on the village council, dealing with the minutiae of local services like refuse collection and road repairs, helped integrate him and his wife, Margaret, into the rural community where they raised two children. He also feels it allowed him to play a bridge-building role between newly-arrived Britons and their French neighbours.

About one-third of the 140 residents of Saint-Martial and its immediate surroundings are British, many of whom were attracted by cheap housing and land. Mr Nixey worries that communication will suffer if he is not around to translate and help smooth out problems and misunderstandings.

Mr Nixey said: “It’s one more wall being built to prevent the further integration of people.

“It is a real shame. I know the ropes. My French is good enough.”

Saint-Martial mayor Pierre Bachellerie said that excluding the British expatriates will be “a big loss” for his and other villages which have been revived by the arrival of British workers and retirees.

He said: “What really upsets me is that they repopulated our villages. We are lucky to have them.

“For me, it’s an aberration that they can no longer vote.”

Press Association