Boris Johnson and his chief adviser are now preparing for the inquiry into the government’s handling of the coronavirus. They both appear to realise that public opinion is turning against them, and that they need to salvage what they can of their reputations.

When the prime minister appeared in front of MPs on the Liaison Committee on Wednesday, he was asked by Yvette Cooper, Labour chair of the Home Affairs Committee, why the government is going to quarantine arrivals to Britain now when it did not do so in the early stages of the outbreak. He said he was following the advice of the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (Sage), which would be published.

He explained the reasoning, making the important point that “Italy closed its border completely to China and yet had an appalling outbreak”, and he went on to say: “People will study all these decisions – I am sure they will – and maybe they will find fault with them, but I can tell you that they were taken in good faith, with the intention to defeat the virus and save lives, and on the best possible scientific advice.”

Download the new Independent Premium app

Sharing the full story, not just the headlines

That sounded to me like a statement to a public inquiry. “Good faith” in particular sounded like Tony Blair giving evidence to one of the four inquiries into the Iraq War. The reference to “intention” also seemed an attempt to forestall the wilder claims that the government deliberately put lives at risk by pursuing a so-called herd immunity strategy. The echo was unmistakable of Blair trying to defend himself against claims that his motive was to secure western oil supplies regardless of the cost in Iraqi lives.

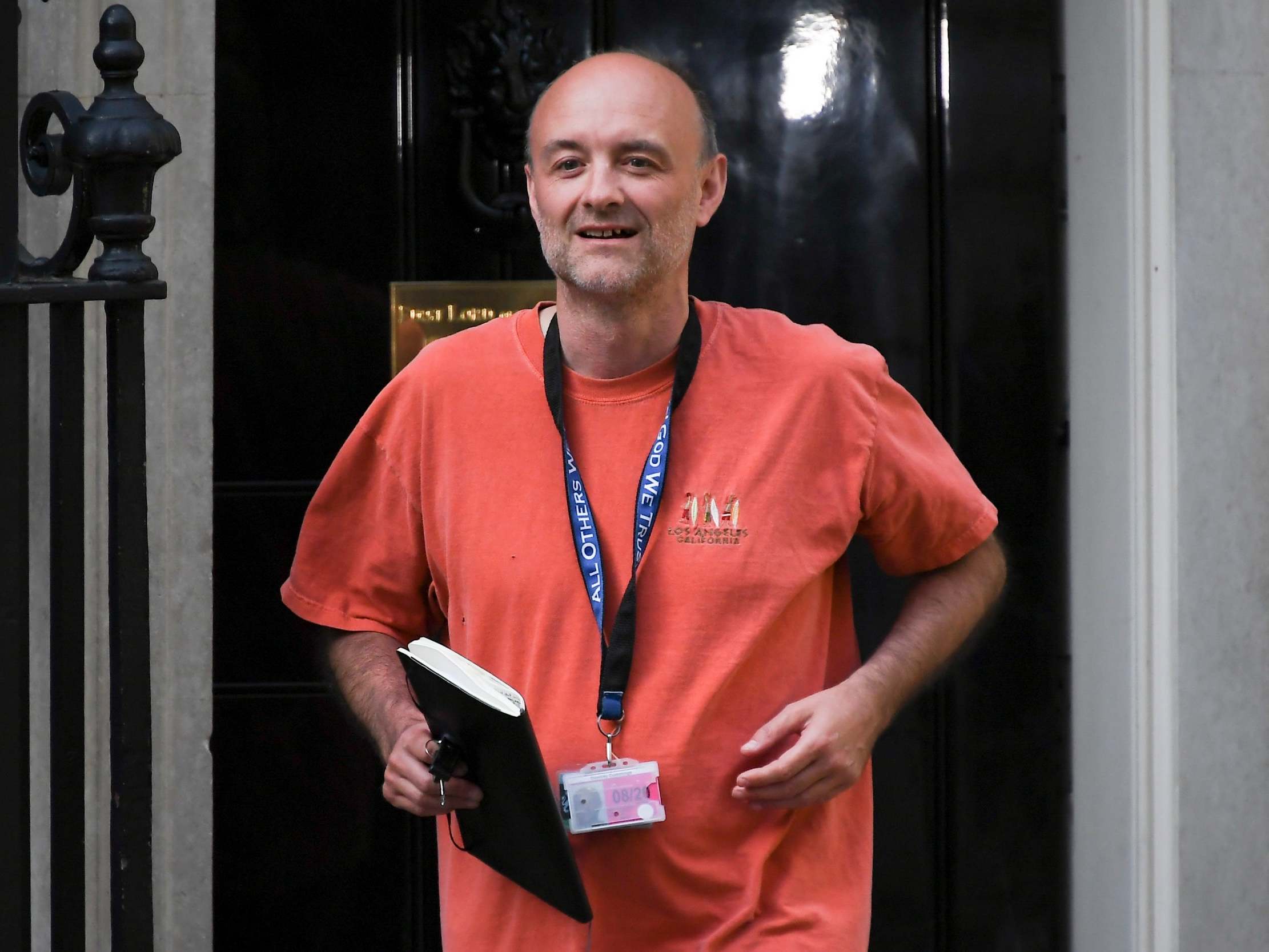

Johnson was not the only person preparing the case for their defence this week. Dominic Cummings, his chief adviser, read out a long statement on Monday defending himself from the immediate charge of breaking lockdown rules, but it included an intriguing paragraph that seemed aimed at a future inquiry.

He complained about reports “suggesting that I had opposed lockdown and even that I did not care about many deaths. For years, I have warned of the dangers of pandemics. Last year I wrote about the possible threat of coronaviruses and the urgent need for planning. The truth is, that I had argued for lockdown. I did not oppose it.”

Unfortunately for him, and thanks to the astonishing internet detective work of Jens Wiechers, a German data scientist, it turned out that the reference to coronaviruses in Cummings’s 2019 blog was added in April this year, on the day Cummings returned from his Durham flit. This undermined Cummings’s claim to have seen it all coming, and is disastrous for his account of himself as an early advocate of shutting the country down.

Which is one of those odd paradoxes that often marks out real life from fiction, because Cummings is probably right that the government was keener to lock down earlier than the scientists. He has now made it even harder for anyone to believe him: the idea is firmly fixed in the public mind that the UK locked down too late because the government ignored the scientists’ warnings.

Indeed, the new batch of Sage minutes published on Friday show that, on 13 March, the committee was “unanimous that measures seeking to completely suppress spread of Covid-19 will cause a second peak” of infections. The minutes also show that Sage said, as early as 18 February, that contact tracing should be abandoned: “When there is sustained transmission in the UK, contact tracing will no longer be useful.”

Nevertheless, Johnson and Cummings are now up against it. They are in a similar position to that in which Blair and Alastair Campbell found themselves as Iraq descended into sectarian chaos. They say they acted in “good faith”, but public opinion decided they had been dishonest in making the case for war, and there was little they could do to change it. Campbell’s departure from government helped, and Blair’s sinuous tenacity allowed him to win another election. But Johnson’s appearance before senior MPs this week provided little evidence that he has the skills needed to turn this round.

This week felt like one of those moments, such as the ejection of the pound from the European exchange rate mechanism in 1992 or the BBC’s allegation that Blair inserted information he knew to be wrong in the intelligence dossier on Iraq, when politics changes. Cummings’s statement reinforced people’s view that he had broken the spirit of the rules, and their anger at Johnson’s refusal to sack him. That should have little to do with people’s overall judgement of how the government has handled the crisis, but it inevitably colours it. It will make it harder for Johnson, or Cummings, to get a fair hearing for their defence, that they acted on the advice of the scientists at all times.

One of the scientists, Professor Chris Whitty, the chief medical officer, said a month ago that the “key metric” to compare the UK’s response with that of other countries is excess deaths – that is, how many more people have died of all causes than the average of recent years. That gets round the problems of countries classifying Covid deaths differently. But the UK has the highest number of excess deaths per million people of any country apart from Spain. That may change, but our death toll is likely to be among the worst when the reckoning is made.

Johnson and Cummings are preparing for the inquiry they know is going to come. They are both trying to get their excuses in early, but they don’t stand a chance because these things are not about facts, they are about the public’s belief that something has gone wrong and that somebody must pay.