In the midst of the global COVID-19 pandemic and antiracist protests, US President Donald Trump, whom scholars and journalists alike are finally coming around to openly discuss as fascist, declared that the United States “will be designating ANTIFA as a Terrorist Organization.” Trump blamed the looting and destruction of property during the protests on a non-existent organization, interchangeably referring to “anarchists.” Trump has even falsely accused a 75-year-old man shoved by police of being an “Antifa provocateur.”

Hardly new concepts, anarchism and antifascism are often mistakenly associated with chaos and violence due to negative propaganda and a general misunderstanding of the concepts. Whilst anarchism, antifascism and antifa are all broadly struggles against oppression, each has its own history, although often overlapping, that can help us to situate a political ideology whose time might have come after nearly a century in exile.

The Tyranny of Algorithmic Order in Times of Revolutionary Change

READ MORE

Anarchists believe hierarchies create oppression, and so they want to decentralize power through consensus-based democracy, requiring much more than a simple majority vote. Today, anarchists are also antifascist — something learned in the Spanish Civil War and the Second World War. They broadly believe in radical equality and mutual aid through local community, and value personal autonomy.

Antifascism has come to signify the struggle against racism, patriarchy, class oppression, colonialism, nationalism, queerphobia and ableism — what antifascists consider the backbone of fascism. Although Susan Sontag advises against using illness as a metaphor, in the midst of a global pandemic, this one feels apt: Antifascists might be better understood as democratic society’s antibodies in defense against virulent fascism.

The Anarchist Ideal

In his book “The Open Society and Its Enemies,” German philosopher Karl Popper distinguishes two main types of government, one in which change can happen without bloodshed, through social institutions that “provide means by which the rulers may be dismissed by the ruled” and those in which rulers can only be changed through revolution. The options thus are democracy (liberty) or dictatorship (tyranny). For the anarchist, society should be based upon both consensus and consent — and always moving toward a more open society.

During the Enlightenment, a radical idea proposing people could govern themselves reemerged: democracy. In its early modern iteration, this idea of self-governance applied only to middle-class white men. Some women, like Olympe de Gouge and Mary Wollstonecraft, made strong arguments for the rights of women and the abolition of slavery. Seeing the aftermath of the American, French and Haitian revolutions, monarchs across Europe panicked, arguing that leaderless anarchy would only result in chaos. At its heart, the concept of democracy promoted a decentralization of power from the few to the many — the anarchist ideal.

Modern anarchism came into focus with Pierre-Joseph Proudhon’s provocative 1840 book “What is Property?” that came to propose an expansion of the ancient shared right of “the commons.” In 19th-century Paris, Proudhon met with the likes of Karl Marx and Mikhail Bakunin. From the onset, anarchists and communists, despite both being on the left, had little patience for one another. Proudhon rejected Marx’s authoritarian tendencies, and Marx considered Proudhon a bourgeois idealist. They both agreed on the dangers of imperialism and capitalism.

Peter Marshall argues that Proudhon imagined a world in which workers would “control their own means of production” and “form small as well as large associations” for industry and manufacturing. For Proudhon, the worker would thus be “no longer a serf of the State, swamped by the ocean of the community” and instead would be a “free man, truly his own master, who acts on his own initiative” while still being beholden to his community.

Proudhon saw the patriarchal family as the origin of authoritarianism and deplored the dominance of governments in everyday life. Proudhon imagined federations of autonomous regions to which a person would consent to belong and contribute. In his system, the larger political units had the fewest powers, and smallest units (the individual) would have the most power. People would also consent to become members of mutual aid associations based around an idea of having shared “commons” and would trade amongst each other — communal living.

The first grand experiment of this occurred with the declaration of the briefly-lived Paris Commune of 1871, in a moment when the French government retreated from Paris in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War. Anarchism eventually found even more success in both Russia and Spain. By the 1930s, millions of people in Spain lived in anarchist collectives.

Who Are the Real Terrorists?

Anarchism came to Americans’ attention with the Haymarket affair of 1886 — a protest both against the murder of workers by police and for an eight-hour work day — when anarchists lobbed bombs at officers in an act of desperation as the police attempted clear the protest.

Just over a hundred years ago, anarchist Emma Goldman wrote about the two principal objections to anarchism she encountered regularly, still familiar today. Anarchism was “impractical, though a beautiful ideal” and that it stood “for violence and destruction.” Goldman defined anarchism as the “philosophy of a new social order based on liberty unrestricted by man-made law; the theory that all forms of government rest on violence, and are therefore wrong and harmful, as well as unnecessary.”

Those two premises both explain the claims of impracticality but also why anarchists have at times been willing to commit destruction or violence. Anarchists commit violence under the assumption that existing governments are violent and unjust themselves and must be changed through revolution, not unlike what was seen in the French and American revolutions. Goldman rejected order “derived through submission and maintained by terror.” As historian John Merriman describes, for Goldman, “it was not anarchist theory that created terrorists but rather the shocking inequalities they saw around them.”

Like socialists and communists, anarchists recognized the revolutionary power of organizing labor and acting as a collective — what they called “anarcho-syndicalism,” or trade unions that operated through direct democracy. For Goldman, social order had to be “based on the free grouping of individuals for the purpose of producing real social wealth” so that to “guarantee to every human being free access to the earth and full enjoyment of the necessities of life, according to individual desires, tastes and inclinations.” In this way, anarchism represents the highest ideals of the Enlightenment.

During the twilight of Weimar Germany in the early 1930s, as Hitler rose to power, the Communist Party created the Antifaschistische Aktion, antifa for short, to combat fascism, which was then understood as being a late imperialist form of capitalism. During the Spanish Civil War, Spanish anarchists, communists, socialists and republicans rose up against the threat of fascism in Spain.

Goldman, by then exiled from the US since 1919, because of her incendiary threat, through the Anarchist Exclusion Act of 1903 (expanded in 1918), organized fundraising efforts against fascism from abroad. As the Nazi threat rose, even the United States — the country from which Hitler’s regime drew inspiration in the creation of its own segregation and miscegenation laws — saw the threat of fascism and collectively decided that the only way to fight it was through the violence of war, ultimately taking an antifascist stance.

In the postwar era, as scholars and activists came to better understand fascism, it became clear that fascism’s strict hierarchies and categories were indeed the antithesis of anarchism in particular. Combatting this articulation of fascism came to define the communal, squatting and autonomous housing movements that arose in Europe and the United States in which anarchist groups took the concept of communal living to also include intentional living and mutual cooperation in their everyday lives. Some anarchist-Catholic groups, inspired by Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin, even found traction. When Spain finally transitioned to democracy in the 1970s, it opted to have autonomous communities rather than provinces or states — a legacy of anarchism.

Anarchism and Antifascism Today

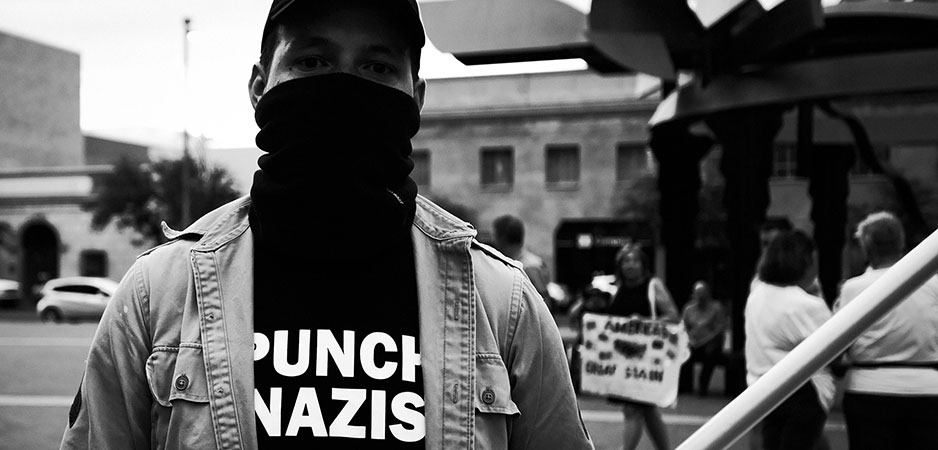

First entering the public imagination during the 1999 World Trade Organization summit in Seattle, Washington, “black blocs” have largely been misunderstood by the media as organized hordes of anarchists roving the street at causing wanton destruction. Rather than an organized body, a black bloc is better understood as an ad hoc gathering of anarchist-leaning people to anonymize themselves by wearing black clothing and masks covering all but their eyes to march in protest.

In “Who’s Afraid of the Black Blocs?”, Francis Dupruis-Déri argues that the tactic of smashing property shows “the ‘public’ that neither private property nor the state, as represented by the police, is sacred,” and indicates “that some are prepared to put themselves in harm’s way to express their anger against capitalism or the state, or their solidarity with those most disadvantaged by the system.” Communist party members, conservative politicians, many anarchist-pacifists, orderly protestors and everyone in between have rejected this tactic. Too often such participants have been called “outside provocateurs” in an attempt to exclude them.

In the 21st century, anarchist tactics of using the occupation of public spaces and strategies to decenter organizing structures reappeared in the Spanish 15th of May Movement in 2011. Inspired in part by the Arab Spring, as unemployment spiked and services were cut, the movement asked for “real democracy now” and was a rebuke of capitalism and the austerity measures imposed because of the economic crisis caused by rampant speculation in the housing market. Borrowing from the anarchist toolbox, the organizers occupied public plazas and streets across Spain during that summer, organized affinity groups and made consensus-based decisions on actions they wanted to take, including the occupation of abandoned buildings so that to place the homeless.

From the onset, affinity groups interested in immigrant rights, feminism, queer issues and racism arose as well. This model was then adapted in September of that year in the Occupy Wall Street protests in the US. Some of these tactics and strategies were later found in the Black Lives Matter protests of 2013, which also drew inspiration from anti-apartheid, Black Power and pan-African movements, amongst others.

Antifa

In anarchist theory, harm caused by capitalism and racism is the result of systemic violence, often obscured. In recent years, anarchists have come to stand against settler colonialism, have advocated for the abolition of the current carceral system and have allied themselves with indigenous people against the US government, as seen in the Dakota pipeline protests. They believe in self-defense and collective defense. In a developing story coming out of Seattle, the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone, a seemingly anarchist-inspired “occupied” area around an abandoned police station, intends to return land to indigenous people from whom it was “stolen” and to established community-based policing.

Since the rise of white nationalist movements, such as Richard Spencer’s alt-right, Gavin McInnes’ Proud Boys and the populism of Donald Trump, antifa’s banner has been lifted to militantly fight what its standard-bearers consider fascism. Pulling the antifascist flag out of the drawer, the antifa movement combined black bloc tactics with antifascist practice and decentered anarchist organizing in order to physically protect innocents at protests under threat from right-wing radicals whilst simultaneously using their own bodies and freedom of speech to disrupt the hate speech of radical-right provocateurs like Spencer and groups like the Atomwaffen Division and the Boogaloo Bois.

Some of these right-wing groups are accelerationists eager to spark a race war, willing to infiltrate antiracist protests themselves to fan the flames. Accelerationism has a long history in communist circles, but less so in anarchism. Used by Vladimir Lenin during the 1917 Russian Revolution, accelerationism was an attempt to bring forward a communist utopia whilst skipping the “bourgeois revolution” Marx believed necessary for a workers’ revolution to take place. More recently, the concept of accelerationism has been associated with the far right and white evangelical Christians waiting for a rapture to spirit them away.

The convicted Norwegian terrorist who killed 77 people in 2011, the Australian man charged with killing 51 Muslims at a mosque in 2018 in Christchurch, New Zealand, and the American charged with the murder of 22 people, and the attempted murder of 23 more, in El Paso, Texas, last year all extolled a belief in their manifestos that their acts would accelerate the arrival of an inevitable race war that would leave the white race supreme.

Given that the world is still in the grip of a pandemic and even peaceful protestors are wearing masks, it is still unclear who has caused the damage and who has looted — and for what reason. Prominent far-right figures like Nicholas Fuentes and his “Groypers” livestreamed from protests and disrupted news reports with their chants, and others, like the Boogaloo Bois, who do believe in accelerationism, have been arrested in Las Vegas and Milwaukee. Although property destruction has often been a black bloc tactic, the FBI has stated there is no evidence of antifa’s involvement during the first week of the protests. Some looters could have been opportunists.

During the current protests around the killing of George Floyd, no clear evidence has indicated that looting or physical violence was started by either anarchists or antifascists. And even if there were violence, one must ask if these were actions against the police or self-protection? Is damage indeed violence against racist statues and property, or is it an attempt at dissent against an already oppressive racist, sexist, classist, nationalistic, queerphobic and ableist political and economic system that has been exacerbated by a global pandemic that has left the most vulnerable jobless and at risk? If the latter, then perhaps we need both the idealism of anarchists and the fortitude of antifascists more than ever.

*[The Centre for Analysis of the Radical Right is a partner institution of Fair Observer.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.