Scott Morrison is the prime minister of Australia. Over the past few months, parts of his country have gone up in flames. Hundreds of homes have been lost in widespread bushfires, and a number of Australians have lost their lives in the inferno. Apparently, the catastrophe at home did not trouble the prime minister. He spent his vacation on the beaches of Hawaii — while his office denied he was there — until public outrage forced him to hurry back home

Australia is a member of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Yet its economy looks more like that of a developing country than an advanced, industrial one — comparable more to Mali, Senegal and Zimbabwe than to Belgium, Italy or Finland.

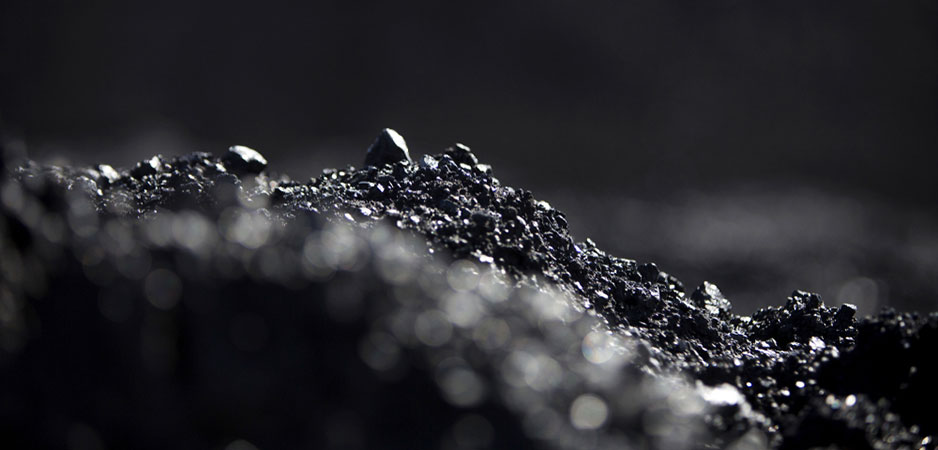

Developing countries often depend on exporting commodities. In the Australian case, that commodity is coal. In fact, Australia is the world’s biggest exporter of coal, which accounts for a large share of its export volume. Much of it goes to China. Although 60% of the country’s electricity is coal-generated, its domestic carbon emissions are relatively low. Its exports, however, account for a whopping 7% of world emissions, which means Australia not only exports coal but also emissions. As a result, Australia has the dubious distinction of being among the major contributors to global warming.

The World After Climate Change

READ MORE

For the Australian government, none of this is cause for concern. In fact, upon his return, Morrison boldly defended his country’s reliance on the coal industry, charging that his government would not “engage in reckless, job destroying and economy crunching targets.” He vowed that he would not “write off the jobs of thousands of Australians by walking away from traditional industries.”

According to the deputy prime minister, Michael McCormack, coal accounts for some 50,000 jobs in Australia. Much of the coal-mining community, however, is concentrated in Queensland, whose electorate proved decisive in the 2019 federal election. The Australian Labor party, once expected to win the election, suffered a crushing defeat, not least because its anti-coal campaign alienated the coal-mining communities in Queensland, who defected en masse to the right. To add insult to injury, coal helped Pauline Hanson — Australia’s radical, right-wing, populist icon — secure a seat in the country’s Senate, where she has proved to be a staunch defender of Queensland’s coal industry. In short, electoral politics trumped environmental concerns.

North

America

This is nothing new. In 2016, US

President Donald Trump carried West Virginia on the promise that he would boost

“clean, beautiful coal” in the Appalachian state and elsewhere. (West

Virginia’s coal mines provide roughly 30,000 jobs.) The coal-mining communities

believed Trump and helped him win the US election.

In environmental terms, his presidency has been disastrous. For coal mining, however, it has been equally disastrous. Coal mines have been closing at an accelerated rate over the past several years, with Trump doing little to reverse the tide. This has nothing to do with environmental concerns. After all, the Trump administration does not “believe” in global warming, at least not in the notion that human behavior might have something to do with it. The reason for the slow decline of West Virginian coal is simple: Coal is no longer profitable, at least not in West Virginia.

The US — and Canada, for that matter, whose environmental record is as bad as that of Australia and America — has always stood out because of its addiction to cheap and plentiful energy. Europe, of course, is fundamentally different. Or is it? Take the case of Germany.

Europe

Germany is not only Europe’s strongest economy, but it also boasts its most significant green party which, polls suggest, might soon hold government responsibilities at the federal level. In addition, Germany has been at the forefront with regard to renewable energy, particularly offshore wind. At the same time, the country has promoted its commitment to a comprehensive “energy transition” — away from traditional, carbon-intensive energy sources.

The reality, however, looks quite different. In 2019, Germany ranked 17th with regard to energy transition — far behind, among others, the Scandinavian countries, Switzerland, the UK and Uruguay. According to the World Economic Forum, Germany was particularly dependent on fossil fuels, especially coal. This is hardly surprising, given Germany’s continued reliance on lignite (brown coal) which, environmentally, is the most toxic kind of coal.

In 2018, no less than one-quarter of Germany’s electricity was generated by lignite power plants. The continued use of lignite for the production of energy was, to a large degree, owed to the tenacious resistance of the lignite industry and its employees. Altogether, the lignite sector accounted for roughly 70,000 jobs. Many of them are concentrated in the eastern part of the country (the former German Democratic Republic, which covered most of its energy requirements with lignite), where in recent years the radical, populist right has made spectacular gains.

Under the circumstances, therefore, it is hardly surprising that some eastern German regional governors have vehemently lobbied against a “premature” exit from lignite. The brown coal might be catastrophic for the environment — among other things, as a result of the destruction of natural habitats associated with surface mining — and noxious for human health, yet this seems to be less important than losing the next election.

These and similar examples provide graphic

illustrations of the hurdles and obstacles in the way to a genuinely radical

“energy U-turn” that goes beyond good intentions. They suggest that we should

expect little to nothing from the political establishment, which will always

find ways to hide behind the ultimate excuse: jobs. Funnily enough, the

establishment showed little concern when thousands of jobs were lost as a

result of ATM machines, to name just one prominent example. Not to mention the

hundreds of thousands of jobs that disappeared as a result of outsourcing and

offshoring.

One of the central tenets of trade theory

is that trade openness only works if the inevitable losers of globalization are

compensated via the welfare state. This explains, as Dani Rodrik noted

decades ago, why more open economies — including relatively small countries

like Austria, the Netherlands and the Nordic nations — tend to have bigger

governments. It stands to reason that the same logic should apply to the energy

transition.

The

Business Community

As so often today, the solution of the

problem (if it is not yet too late) does not come from politics, but from the

business community. Again, the Australian case is instructive. From what national

media have reported — and Australia’s coal-aficionado prime minister has

deplored — a growing number of major Australian businesses are no longer

prepared to “provide banking, insurance and consulting services to an

increasing number of firms in the coal sector.”

This has not gone over well with Prime Minister Morrison. Kowtowing once again to the powerful coal lobby, he came up with a rather absurd proposition, namely to outlaw “indulgent and selfish” activist-driven boycott campaigns against the coal industry. Obviously, Morrison, not unlike Trump, appears to lack even a minimal sense and appreciation of the irony involved. It is a sign of the times — and not a particularly encouraging one — when it is business that refuses to be blackmailed by a small, yet powerful “indulgent and selfish” minority.

The Australian “model” might prove contagious. Just recently, Goldman Sachs announced it would no longer “invest in new thermal coal mines anywhere in the world.” Nor will it finance oil exploration ventures in the Arctic. At the same time, institutional investors, such as pension funds, have started to put pressure on the mining industry in an open revolt against the coal lobby’s obstructive tactics. Under the circumstances, the days of the likes of Scott Morrison, Donald Trump and, for that matter, Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro are hopefully numbered.

The views expressed in this article

are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial

policy.