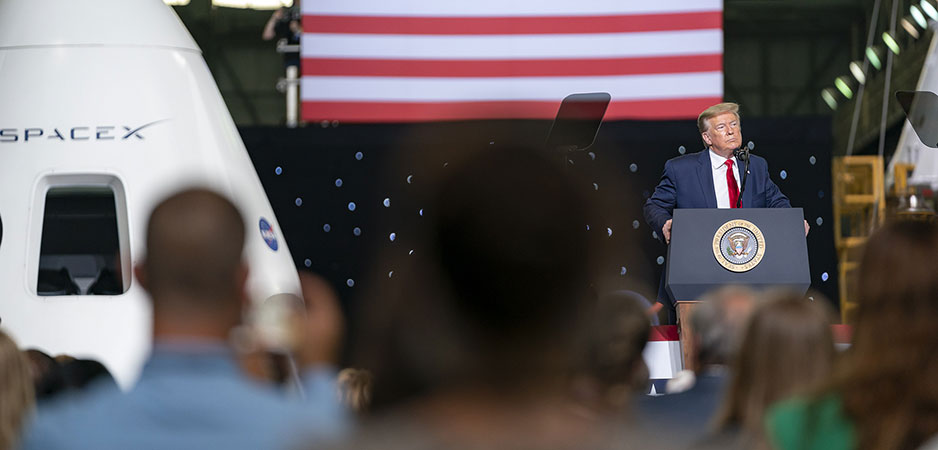

As the revolt was beginning to brew on streets across the nation on May 30, US President Donald Trump was celebrating the success of SpaceX’s launch of a manned mission to the international space station, the first time a private company has put human beings in space. Although it increasingly appears that Trump may come in second in November’s election, he proudly proclaimed, “We are not going to be number two anywhere.”

Here is today’s 3D definition:

Number two:

1. Among the honored few

2. Shamefully distanced by some other undeserving competitor

Contextual Note

When Trump announced his policy of “America First” upon taking office in 2017, he indicated that he would never accept coming in second. He remains proud of an economy that is still No. 1 in the world, even if he should know by now that it will be overtaken by China in the near future. He is particularly proud of having “rebuilt” a “depleted” — in reality, bloated — military that has always been No. 1 and dwarfs even the accumulated military budgets of the next seven countries.

Trump not only wants to be No. 1 in everything, but he has dedicated himself to the idea of domination. What better way to prove that you are not No. 2? Referring to the massive uprising that has crippled cities across America, he made his intentions clear on June 1. “The president and Attorney General William Barr used the word ‘dominate’ nearly a dozen times in describing how law enforcement should posture themselves,” ABC News reports.

The idea of No. 1 and No. 2 have a special but, at the same time, ambiguous meaning in US culture. To the extent that Americans are taught to feel that everything in their lives should be seen as part of a competitive race, it is considered unmanly and shameful to aim for anything other than the top spot. Everyone wants to be seen as the leader, which may seem paradoxical at this moment in history in which leadership in times of crisis is nowhere evident.

When, in normal times, professional sports are actually being played, the media constantly surveys which teams are leading the league. They also regularly track for their audience who is the richest billionaire, which records have just been broken, which movies will win academy awards and who ate the most hot dogs in 10 minutes.

This focus on No. 1 contrasts with the Olympic Games, in which coming in second or third carries a high degree of honor and no sense of shame, even for Americans. An athlete who achieves silver or bronze has obtained a prize for the nation, has added to a winning score and has projected the nation’s image forward in its competition against every other nation in the world. It may be a weak reminder of our mercantilist past, but money is metal and a medal in the Olympics is money.

The problem is that no individual or nation can remain No. 1 forever. As the Daily Devil’s Dictionary recently reminded readers, Hertz had forever been the uncontested leader in the car rental industry, a position that was never seriously threatened until its declaration of bankruptcy last month.

Avis, a rival to Hertz, achieved its success thanks to a brilliant advertising campaign launched in 1962 that highlighted the significance of being No. 2. It meant trying harder and focusing on customers’ needs rather than dedicating itself to vainly and selfishly defending a position as No. 1. Avis cheekily demonstrated the importance of not being No. 1, which sounded like a heretical proposition in US culture. This was a decade before the slogan, “Small is Beautiful” came to the fore, an idea that radically contradicts traditional US cultural values.

In a rational world, the focus on No. 1 may well define a goal, but achieving a high ranking is perfectly honorable. For Americans, coming in second or third or even 10th offers proof of the value of competition. After all, the point of competition is not just to isolate the leader for special admiration but also to identify the elite, those who have a right to dominate. Competition defines a group of high performers who can strut proudly among their peers and advertise their sense of accomplishment. In such a system, everyone else is an anonymous loser. Those are the people we now see in the streets defying curfew orders. That’s how natural hierarchies are established, which in normal times no one has the right to complain about.

So, being No. 2 is something anyone should be able to live with. But not Trump. Only pathological narcissists are fixated on always being No. 1. That’s why recent presidents didn’t force the issue on manned space flights or obscenely expanding military technology. True members of the elite have no problem giving way to other leaders while focusing on how they can collectively manage their dominant position.

On the other hand, many of the losers, those who can never hope to join the elite and have no ranking to defend, tend to admire the narcissists precisely for their fixation on being No. 1. That may be the best explanation for Trump’s election in 2016. Whether it can work again for him in 2020 remains to be seen.

Historical Note

For the past nine years, Russia has been alone in the manned space race. The US proved its point long ago about its ability to do spectacular things beyond the earth’s atmosphere. The expense no longer justified the prestige such accomplishments brought. And to the extent that under the Obama administration, the US and Russia were cooperating and collaborating on a project focused on a scientific rather than a political goal, it seemed advantageous to many that the Russians should be making the investments and taking the risk with people’s lives.

Back in 2007, Nobel laureate Steven Weinberg summarized the reasons why the US could be happy to be No. 2: “The International Space Station is an orbital turkey. No important science has come out of it. I could almost say no science has come out of it. And I would go beyond that and say that the whole manned spaceflight program, which is so enormously expensive, has produced nothing of scientific value.”

One commentator reminds us that if it is not about science, it’s about politics. “Manned spaceflight has always had political motives,” Joshua Filmer writes. During the Cold War, from Sputnik in 1957 to the first moon landing in 1969, it really was about proving who was No. 1 in the contest between the God-fearing US capitalists and the atheistic Soviet communists. Both sides had scored a victory. After that, US-Russia relations “improved when their respective spacecrafts docked with each other in orbit in 1975, heralding an end to the ‘war’ and serving as a symbol that the two superpowers were moving ahead to a new era.”

That was five years before the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980, who would brand the Soviet Union the “evil empire” instead of pursuing collaboration on scientific research. This led to the former actor’s “Strategic Defense Initiative,” quickly renamed the “Star Wars” program, reinforcing the notion that Washington had become not just a sub-precinct of Hollywood, but also the epicenter of hyperreality.

In 1989, the Berlin Wall came down and the evil empire was in agony. Competition in a space race no longer made any sense. At the time, some people even imagined that Francis Fukuyama was on to something when he described the “end of history, ” which left the neoliberal order as “the last man” standing. When you’re alone, you know you’re No. 1.

In some ways, that status of being alone seems to define Donald Trump’s ambition. “America First” means two contradictory things: America dominates and America is its own universe. It is contradictory because dominating implies recognizing the existence of others. But the idea of America as the “last man” suggests the belief that all the others are slaves. They exist physically but they have no legal or cultural status.

That may summarize Trump’s worldview. It is the one shared by his base as well as all the Hannitys and Ingrahams at Fox News. Any resemblance with historical fascism may simply be a coincidence, though the latest images from the streets of US cities may reinforce that impression.

*[In the age of Oscar Wilde and Mark Twain, another American wit, the journalist Ambrose Bierce, produced a series of satirical definitions of commonly used terms, throwing light on their hidden meanings in real discourse. Bierce eventually collected and published them as a book, The Devil’s Dictionary, in 1911. We have shamelessly appropriated his title in the interest of continuing his wholesome pedagogical effort to enlighten generations of readers of the news. Click here to read more of The Daily Devil’s Dictionary.]

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Fair Observer’s editorial policy.