Japan has given Britain just six weeks to sign up to a post-Brexit trade deal or face disruption to its imports and exports.

In the latest sign that the “swashbuckling” drive to sign deals with countries around the world is proving less than straightforward, the UK could lose favourable access to Japanese markets it enjoyed as part of EU membership if no agreement is signed.

UK negotiators also face the prospect of being being bounced into a deal on unfavourable terms, as countries like Japan seek to use the reopening of deals to gain further concessions against the UK.

Download the new Independent Premium app

Sharing the full story, not just the headlines

Japanese negotiators this week piled extra pressure onto Boris Johnson by accelerating the timeline for a deal, citing a lack of time in their parliamentary calendar.

“To avoid a gap in January, we must pass this in the autumn session of the Diet [the Japanese parliament],” Hiroshi Matsuura, Tokyo’s chief negotiator, told the Financial Times. “That means we must complete negotiations by the end of July.”

Mr Matsuura added that the UK and Japan would have to “limit our ambitions”, casting doubt on UK ambitions to improve access for sectors like agricultural produce.

The European Union has a trade deal with Japan but Britain will no longer benefit from it from the start of 2021 when the Brexit transition period ends.

Like some countries with EU trade deals, Japan has declined to simply roll over its existing agreement for the UK after Brexit and has instead reopened talks, potentially extracting further concessions from the UK.

Dr Anna Jerzewska, associate fellow at the UK Trade Policy Observatory told The Independent: “It’s important to note that Japan has been one of the countries that the UK did not manage to negotiate a continuity agreement with – agreements that were supposed to provide continuity of trade with countries that the UK has a trade agreement under EU membership.

“Japan has been quite cautious about agreeing to new trade terms with the UK while the UK-EU negotiations were ongoing. At the same, many Japanese companies have made long-term investments in the UK as the gateway to the EU market – those investments will be heavily impacted by the end of the year when the transition period ends. Even a UK-EU FTA will not allow Japanese companies to maintain current supply chains,” she said.

The latest news on Brexit, politics and beyond direct to your inbox

“The deal is likely to be limited to current concessions under the EU-Japan agreement rather than provide any additional benefits for the UK. The agreement will be much more of a continuity agreement than a new, comprehensive deal. From the Japanese perspective, it would be aimed at securing as much of its current UK supply chains as possible. For example, Japan would likely be willing to agree to a form of cumulation of origin that would ensure that Japanese products can still be considered as originating inputs for goods exported to the EU and vice versa.”

She said that the Japanese Government is “well aware of what the lack of a continuity agreement would mean for Japanese businesses”, suggesting it would be keen to sign an agreement in time and avoid disruption to its own businesses.

British officials say they will not accept “rollbacks” on UK market access to Japan and that both sides have already agreed to work quickly to provide continuity at the end of the year.

A Government spokesperson said: “Both sides are committed to an ambitious timeline to secure a deal that will enter into force by the end of 2020 if at all possible. Our priority is to maintain and enhance the trading relationship between our two countries.”

Elsewhere in the trade sector, there is still concern that British borders may not be ready for the UK’s economic break with the EU at the end of a year.

1/37

Pro-Brexit supporters celebrating in Parliament Square, after the UK left the European Union on 31 January. Ending 47 years of membership

PA

2/37

Big Ben, shows the hands at eleven o’clock at night

AFP via Getty

3/37

Pro Brexit supporters attend the Brexit Day Celebration Party hosted by Leave Means Leave

Getty

4/37

Brexit Party leader Nigel Farage smiles on stage

AFP/Getty

5/37

People celebrate in Parliament Square

Reuters

6/37

A Brexit supporter celebrates during a rally in Parliament square

AP

7/37

Police form a line at Parliament Square to prevent a small group of anti-Brexit protestors from going through to the main Brexit rally

PA

8/37

Nigel Farage speaks to pro-Brexit supporters

PA

9/37

PA

10/37

JD Wetherspoon Chairman Tim Martin speaks as people wave flags

Reuters

11/37

Getty

12/37

Brexit supporters wave Union flags as they watch the big screen

AFP via Getty

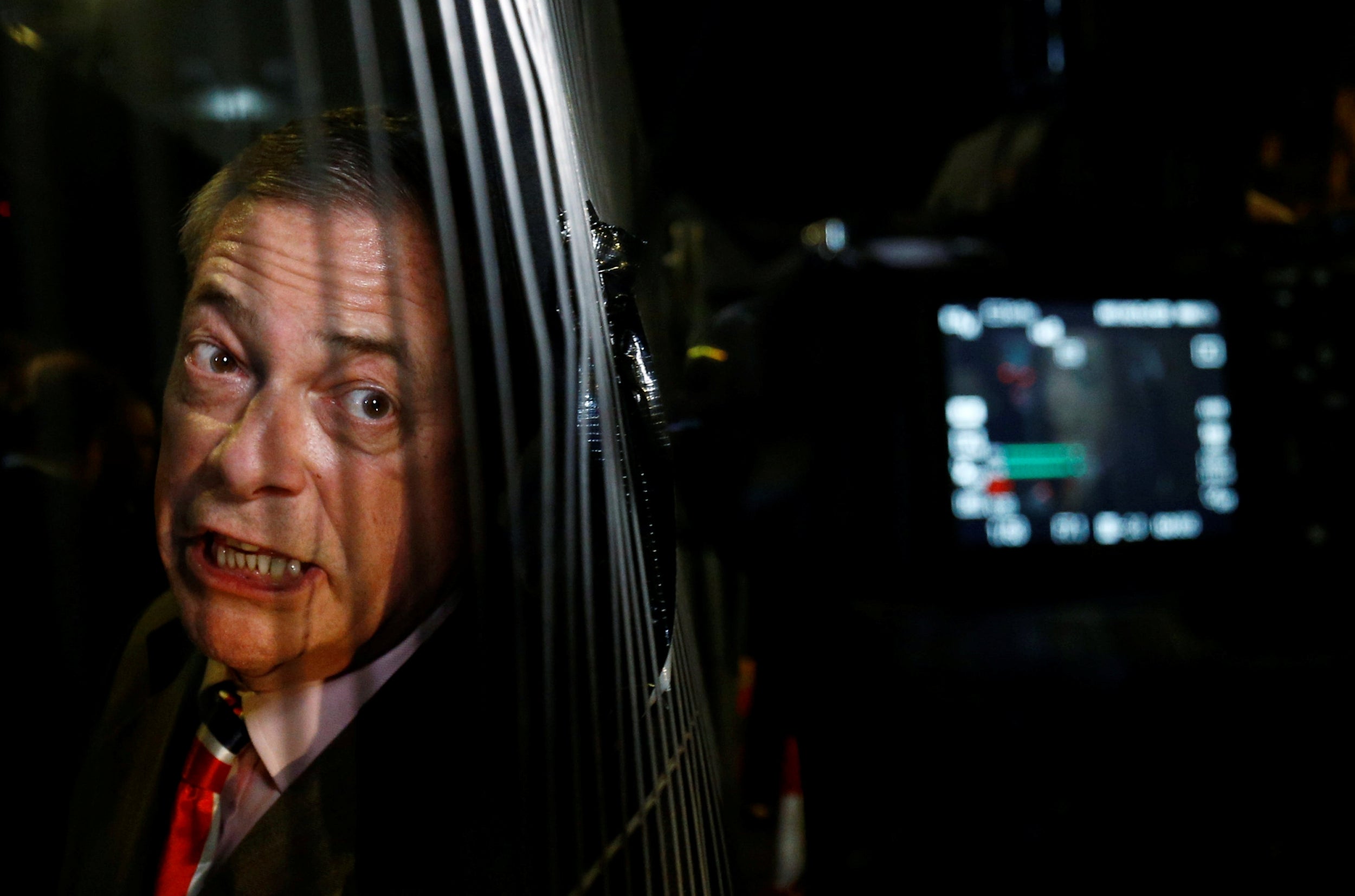

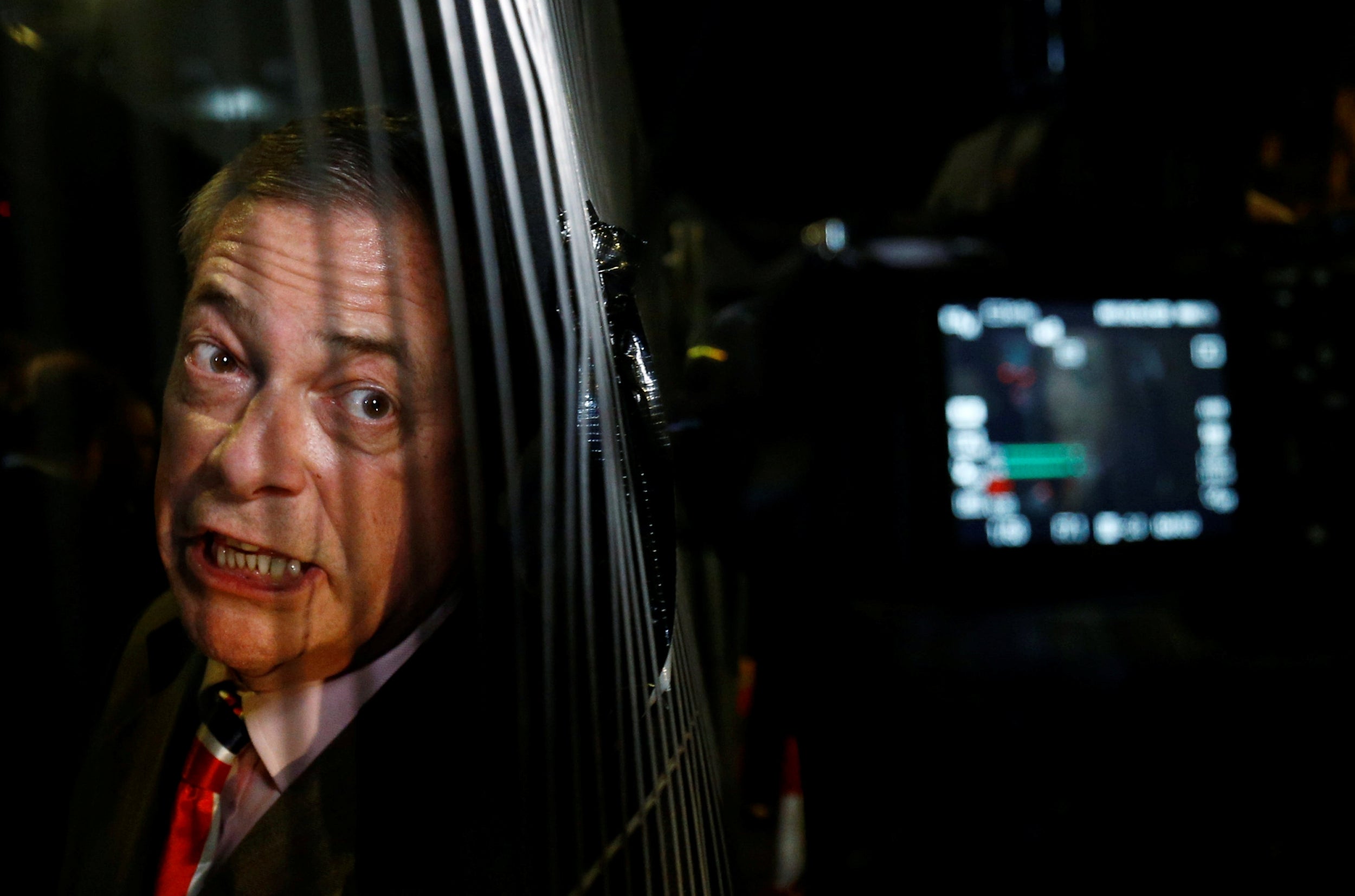

13/37

Brexit Party leader, Nigel Farage arrives

Reuters

14/37

Brexit supporters gather

AP

15/37

Ann Widdecombe speaks to pro-Brexit supporters

PA

16/37

Brexit supporters wave Union flags as they watch the big screen

AFP via Getty

17/37

AFP via Getty

18/37

People wave British Union Jack flags as they celebrate

Reuters

19/37

Pro-Brexit demonstrators celebrate on Parliament Square on Brexit day

Reuters

20/37

A pro-Brexit supporter jumps on an EU flag

PA

21/37

Getty

22/37

AFP via Getty

23/37

PA

24/37

Getty

25/37

AP

26/37

Getty

27/37

A man waves Union flags from a small car as he drives past Brexit supporters gathering

AFP via Getty

28/37

A pro-Brexit supporter pours beer onto an EU flag

PA

29/37

Getty

30/37

An EU flag lies trampled in the mud

Getty

31/37

Getty

32/37

PA

33/37

PA

34/37

Getty

35/37

Getty

36/37

PA

37/37

AFP via Getty

1/37

Pro-Brexit supporters celebrating in Parliament Square, after the UK left the European Union on 31 January. Ending 47 years of membership

PA

2/37

Big Ben, shows the hands at eleven o’clock at night

AFP via Getty

3/37

Pro Brexit supporters attend the Brexit Day Celebration Party hosted by Leave Means Leave

Getty

4/37

Brexit Party leader Nigel Farage smiles on stage

AFP/Getty

5/37

People celebrate in Parliament Square

Reuters

6/37

A Brexit supporter celebrates during a rally in Parliament square

AP

7/37

Police form a line at Parliament Square to prevent a small group of anti-Brexit protestors from going through to the main Brexit rally

PA

8/37

Nigel Farage speaks to pro-Brexit supporters

PA

9/37

PA

10/37

JD Wetherspoon Chairman Tim Martin speaks as people wave flags

Reuters

11/37

Getty

12/37

Brexit supporters wave Union flags as they watch the big screen

AFP via Getty

13/37

Brexit Party leader, Nigel Farage arrives

Reuters

14/37

Brexit supporters gather

AP

15/37

Ann Widdecombe speaks to pro-Brexit supporters

PA

16/37

Brexit supporters wave Union flags as they watch the big screen

AFP via Getty

17/37

AFP via Getty

18/37

People wave British Union Jack flags as they celebrate

Reuters

19/37

Pro-Brexit demonstrators celebrate on Parliament Square on Brexit day

Reuters

20/37

A pro-Brexit supporter jumps on an EU flag

PA

21/37

Getty

22/37

AFP via Getty

23/37

PA

24/37

Getty

25/37

AP

26/37

Getty

27/37

A man waves Union flags from a small car as he drives past Brexit supporters gathering

AFP via Getty

28/37

A pro-Brexit supporter pours beer onto an EU flag

PA

29/37

Getty

30/37

An EU flag lies trampled in the mud

Getty

31/37

Getty

32/37

PA

33/37

PA

34/37

Getty

35/37

Getty

36/37

PA

37/37

AFP via Getty

Alex Veitch, head of international policy at the Freight Transport Association told a parliamentary committee on Tuesday that lack of an EU-UK trade deal would still require tens of thousands of new customs agents – though he downgraded an existing industry estimate of needing 50,000 recruits.

“We don’t have a free trade agreement [with the EU] you would need a substantially greater number of customs agents,” he said.

“My take on it is it’s probably more like 35,000, 40,000, perhaps less than 50,000 – but these numbers are all estimates.”

Since the 50,000 estimate was made the UK has announced plans for a new transition period under which some of the new bureaucracy imposed on businesses would be delayed until July, to give firms breathing space to prepare.