Beto O’Rourke

Beto O’Rourke’s ancestors were slaveholders, records reveal

Exclusive: O’Rourke addresses family history for the first time and admits that he and his children are ‘beneficiaries’ of slaveholding

Photograph: Drew Angerer/ Getty Images

Democratic presidential candidate Beto O’Rourke recently delivered an impassioned speech while meeting with the Gullah-Geechee Nation, an organization of African Americans whose ancestors were enslaved on plantations from Florida to South Carolina.

The speech in Beaufort followed one attendee’s question about whether O’Rourke supports reparations, the idea of compensation for the descendants of slaves.

“Yes,” he answered. “We must repair this country from its very founding: kidnapping people from west Africa, bringing them in bondage to literally build the wealth of the United States” and not allowing African Americans “to share in the fruits” of their ancestors’ labor.

A full accounting of this historical outrage was needed, O’Rourke said, adding: “Today, white America does not know this story.” A path to reparations, he said, will come only “through telling, learning and sharing this American story with everyone”.

However, O’Rourke has never publicly shared the slave-owning story of some of his own family.

O’Rourke is listed as a member on Ancestry.com, where abundant documentation exists of his and his wife Amy’s ancestors’ slave-owning and their support for the Confederacy. In his writings and media interviews, however, O’Rourke has dealt only with kin who lived too late to have fought for the south in the American civil war, or to have been slave masters.

In an interview, O’Rourke said that he and his wife knew nothing about their ancestral ties to the Confederacy and slave holding until he was contacted by the Guardian. Amy O’Rourke declined to be interviewed.

Rose and Eliza

O’Rourke often talks about the Irish-immigrant roots of his father, the late Patrick Frances “Pat” O’Rourke. One of Pat’s great-grandfathers, Bernard “Barney” O’Rourke, immigrated from Ireland, apparently in the 1860s. He lived in the midwest, worked on the railroads, and had no connection with the antebellum south.

O’Rourke has also acknowledged his Welsh-immigrant great-grandmother, who arrived in the United States in the early 20th century.

O’Rourke said he visits Ancestry.com about once a year but has never researched any kin besides those on his father’s Irish side. To look into the rest of the family, O’Rourke said, would have taken “time I don’t have”.

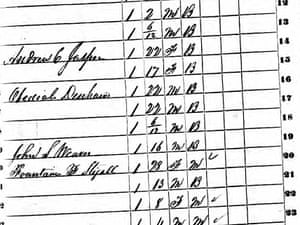

But one of his grandmothers, Mildred Jasper O’Rourke, came from an old, southern family. Her great-grandfather, Andrew Cowan Jasper, lived in Kentucky in the early 19th century. The Federal Slave Census of 1850 lists him as owning two young women, one 22 years old and the other 17. Census enumerators during the period recorded owners’ names, but only the gender and ages of enslaved people.

In 1856, Andrew Jasper moved from Kentucky to Kansas territory with his family and the enslaved women. He died a year later, and his estate was probated. The enslaved women, who by then were 27 and 23, were identified in the estate papers as Rose and Eliza.

The executor of the estate hired an appraiser to price Rose and Eliza – at $800 a piece. The two were then put out for hire, and the executor spent $5.05 to buy them work clothes. During the next few weeks, the enslaved women earned Jasper’s widow and children $29.58. Calculating the 60 hours per week of labor they probably did, that comes out to about $4,000 in today’s dollars.

The executor organized a “crying sale”, today known as an estate auction. Among the items liquidated were plows, horses, cows, calves, rifles, a grindstone – and Rose and Eliza.

O’Rourke said he was moved to learn of the two women whom Jasper enslaved.

“Amy and I sat down and talked through this,” O’Rourke said. “How Andrew was able, through his descendants, to pass on the benefits of owning other human beings. And ultimately I and my children are beneficiaries of that.”

The realization has affected him deeply, he said, adding: “I don’t know if I’ve got the words for it.” O’Rourke later elaborated on this in a post on Medium, writing: “We all need to know our own story as it relates to the national story, much as I am learning mine.”

Peter, Darsy, Sally, Ned, Moses

O’Rourke also has antebellum southern ancestry on his maternal side. His mother is Melissa Williams O’Rourke, and Melissa’s father – O’Rourke’s grandfather – was Robert Lee Williams Jr, after whom Beto was named.

The family was from Georgia, and Robert Lee Williams’s grandfather – Beto’s great-great-grandfather – was Columbus Marion Williams. Columbus joined the Confederate forces when he was 16, along with his 44-year-old father, Frederick Samuel Williams.

O’Rourke’s wife, Amy Sanders O’Rourke, also has Confederacy and slaveholding roots. Her great-grandmother, Margaret Fieulle, was surnamed Levy before she married, and her grandfather was Richard B Levy. Richard hailed from a family of Presbyterians, many of who became Episcopalians after the civil war.

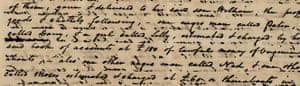

The Levys were planters in Tidewater Virginia, starting in the 18th century. A 1798 probate record, available online, memorializes an argument among the extended family over who would inherit several enslaved people: “one negro man called Peter”, “a boy called Darsy”, “a girl called Sally”, a “negro man called Ned” and “one other called Moses”.

Richard B Levy fought for the Confederacy and was with Robert E Lee at his surrender at Appomattox in 1865. A few years later Richard moved to Longview, Texas – a city that would experience five lynchings between 1888 and 1919, and a white-instigated race riot that ended with the black side of town burned down.

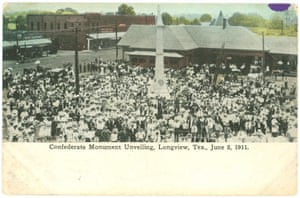

During the Jim Crow era, the United Daughters of the Confederacy founded a chapter in Longview and named it after Richard B Levy. The UDC’s mission was to preserve laudatory ideas about the antebellum south – including the Confederacy and slavery – among future generations of white people.

To that end, the UDC distributed books to school libraries that justified white supremacism, and they erected scores of celebratory monuments throughout the south. In 1911, the Richard B Levy chapter placed a statue of a Confederate soldier in downtown Longview. Thousands of people attended the unveiling and, according to historical accounts, roared with delight when “Dixie” was sung. Margaret Levy pulled the canvas off the statue.

More than a century later, it still stands in Longview. The Richard B Levy UDC chapter is still listed with the IRS as a non-profit organization.

Countless Americans could share similar family stories – if they knew them. Almost 2 million white people in the antebellum south owned 4 million slaves. Today the number of descendants of slave owners runs in the tens of millions, encompassing people living throughout America, with political leanings that span the spectrum from right to left.

But few white people have explored this uncomfortable side of their genealogy: they “mostly want to distance ourselves from it”, said Thomas deWolf, who directs the organization Coming to the Table. It promotes explorations of genealogy, and interracial communication, among the descendants of white enslavers and African American enslaved.

DeWolf, who is white, is author of Inheriting the Trade: A Northern Family Confronts Its Legacy as the Largest Slaveholding Dynasty in US History. His Rhode Island ancestors, who brought thousands of slaves to the Caribbean and the American south from west Africa, are the subject of the book.

“Most people think that ‘reparations’ means writing checks” to people living today, who were never enslaved, DeWolf said. But, he noted, the word is rooted in “repair”.

For Coming to the Table, repairing America’s slave holding past includes white people working for structural change: eradicating racism from the justice system, for example and abolishing racial inequalities in public education.

For DeWolf, doing genealogy work, and telling the particular histories it unearths, is a precursor to structural repair. Americans need to “gather together in the grief of it all”, he said. He quoted his cousin, Katrina Browne, who testified in June at congressional hearings for HB40, a House bill, which, if passed, would create a commission to study the issue of reparations: “It is good for the soul of a person, a people and of a nation to set things right.”

O’Rourke said he agrees. He said he would like to try to find Eliza’s and Rose’s descendants.

In the meantime, he said his ancestors’ slaveholding and participation in the Confederacy is “a part of my family history I will share on the campaign trail”.