Angela Rayner has won the race to be Labour’s deputy leader, a result that has long felt almost inevitable.

The shadow education secretary built a commanding early lead which she sustained throughout the 12-week contest, despite running a relatively low-profile campaign.

Rayner clearly struggled with the idea of being the frontrunner, saying in interviews that she had spent her life as the “underdog”, facing hurdles that many of her parliamentary colleagues could never imagine.

Download the new Independent Premium app

Sharing the full story, not just the headlines

Indeed, in a parliament often derided as pale, male and stale, Rayner has long stood out.

Born in Stockport, in Greater Manchester, in 1980, Rayner was raised on a council estate by her mother Lynn, who struggled with depression and could not read or write. From a young age, Rayner acted as a carer for her mother, at times having to bathe and feed her.

At one point, Rayner was forced to have her mother admitted to a mental health ward because she was struggling with suicidal thoughts.

Rayner has spoken movingly about being told she would “never amount to anything” after becoming pregnant at 16 and leaving school without any qualifications. She credits New Labour’s Sure Start centres, where she took a parenting course, with helping her find her feet.

Showing the determination that would later power her political career, Rayner went to college part time and then got a job as one of the youngest home helps in Stockport.

She became a trade union representative, later rising to become Unison’s most senior official in the northwest.

In 2015 Rayner was elected as MP for Ashton-under-Lyne. In her maiden speech, she talked of how her detractors put her down, saying: “If only they could see me now.”

She nominated Andy Burnham to be Labour leader in 2015 but she was one of few MPs who supported Jeremy Corbyn when he was challenged by Owen Smith the following year.

The latest news on Brexit, politics and beyond direct to your inbox

This loyalty earnt her a place on the front bench as shadow education secretary, a role she held for the entirety of Corbyn’s tumultuous leadership.

She was close to team Corbyn during this period but not in the inner circle. Her nominations for the deputy leadership came from across the different parts of the parliamentary party, from left wingers such as her friend Rebecca Long-Bailey and Lloyd Russell-Moyle, to moderates such as Yvette Cooper and Rachel Reeves.

Plenty of MPs have said privately that they wish she had gone for the top job instead of backing Long-Bailey, her friend and flatmate. Rayner has spoken openly about the challenges women from her background face, which clearly played a part in her decision to run for the number two role.

But keeping her powder dry may also prove smart in the long run, considering the uphill battle the new party leader faces.

Out in the country, she received more than four times the number of constituency party nominations than her nearest rival Dawn Butler, by 363 to 82. And she won the backing of several big unions – a critical step for any MP with leadership ambitions.

Rayner’s significant early lead meant the other candidates had to be more outspoken and colourful to attract attention.

By contrast, her campaign was relatively low profile – one of her few similarities with Boris Johnson, who ran an almost submarine-like bid to be Conservative leader in 2019.

The Ashton-under-Lyne MP was careful not to squander her lead, making thoughtful interventions and granting relatively few interviews.

Her down-to-earth nature and her honesty over her early experiences of deprivation appear to have done much of the heavy lifting for her, making her relatable to many voters.

A pragmatist at heart, Rayner based her deputy leadership campaign on calls for “everyday socialism that’s rooted in peoples lives”.

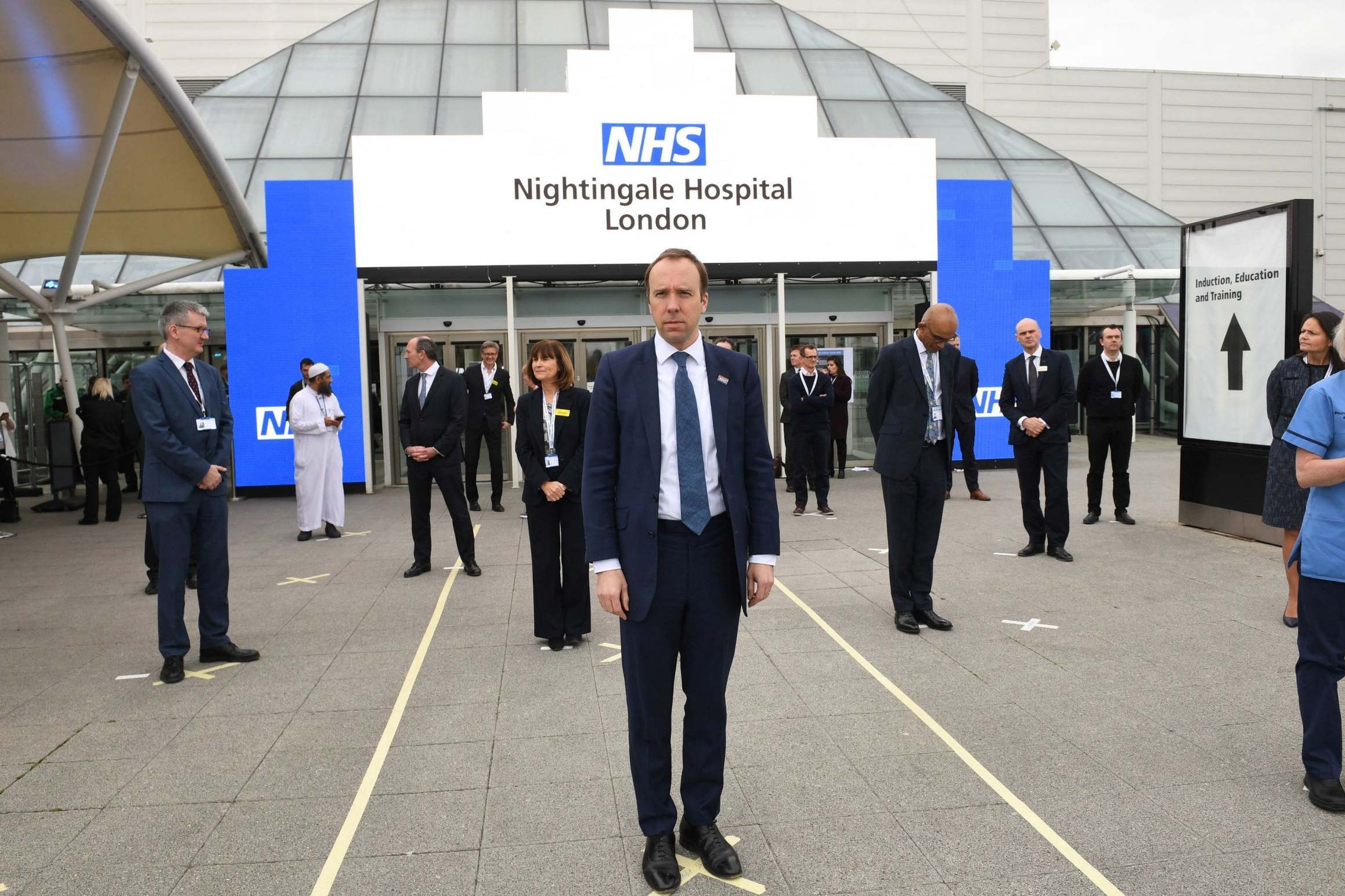

1/50 3 April 2020

Health Secretary Matt Hancock and NHS staff stand on marks on the ground, put in place to ensure social distancing guidelines are adhered to, at the opening of the NHS Nightingale Hospital at the ExCel centre in London, a temporary hospital with 4000 beds which has been set up for the treatment of Covid-19 patients. PA Photo. Picture date: Friday April 3, 2020. Split into more than 80 wards containing 42 beds each, the facility will be used to treat Covid-19 patients who have been transferred from other intensive care units across London.

PA

2/50 2 April 2020

A child at Westlands Primary School paints a poster in support of the NHS in Newcastle-under-Lyme

Reuters

3/50 1 April 2020

Staff wearing PPE of gloves and face masks, as a preactionary measure against Covid-19, disinfect an ambulance after it arrived with a patient at St Thomas’ Hospital in north London

AFP via Getty

4/50 31 March 2020

Llandudno Pier remains closed and deserted of tourists during the pandemic lockdown in Wales

Getty

5/50 30 March 2020

Waves break against the pier at Tynemouth, on the North East coast

PA

6/50 29 March 2020

Waves crash over a car on the seafront during windy conditions in Broadstairs, Kent

PA

7/50 28 March 2020

Derbyshire Police dye the “blue lagoon” in Harpur Hill, Buxton black, as gatherings there are “dangerous” and are “in contravention of the current instruction of the UK Government”

PA

8/50 27 March 2020

A road sign advising drivers to ‘stay home protect NHS saves lives’ is visible on the M80 near Banknock as the UK continues in lockdown to help curb the spread of the coronavirus

PA

9/50 26 March 2020

A postman wears a mask and gloves to deliver letters in Broadstairs, Kent, after Prime Minister Boris Johnson has put the UK in lockdown to help curb the spread of the coronavirus. PA Photo. Picture date: Thursday March 26, 2020. The UK’s coronavirus death toll reached 463 on Wednesday.

PA

10/50 25 March 2020

Members of the public out exercising on Brighton beach at sunset

Getty

11/50 24 March 2020

Military vehicles cross Westminster Bridge after members of the 101 Logistic Brigade delivered a consignment of medical masks to St Thomas’ hospital

Getty

12/50 23 March 2020

Commuters travel on the London underground during the Coronavirus pandemic

Getty

13/50 22 March 2020

People walk on the seafront after recent incidents of members of the public ignoring government advice on social distancing on in Hove

Getty

14/50 21 March 2020

A general view of an empty Trafalgar Square in London. There have as of now been 3,983 diagnosed coronavirus cases in the UK and 177 deaths

Getty

15/50 20 March 2020

Swans swim on the banks of the River Severn in Worcester

PA

16/50 19 March 2020

A piece of art by the artist, known as the Rebel Bear has appeared on a wall on Bank Street in Glasgow. The new addition to Glasgow’s street art is capturing the global Coronavirus crisis. The piece features a woman and a man pulling back to give each other a kiss

PA

17/50 18 March 2020

Students tend to Spring Lambs at Moreton Morrell College in Warwickshire

PA

18/50 17 March 2020

Caerphilly Castle in South Wales joins Tourism Ireland’s Global Greenings campaign to mark St Patrick’s Day

PA

19/50 16 March 2020

Shoppers form long queues ahead of the opening of a Costco wholesale store in Chingford

Getty

20/50 15 March 2020

Players sing songs in the changing room after their game of football at Hackney Marshes in London

Reuters

21/50 14 March 2020

Empty shelves in the laundry aisle of an Asda store in London

PA

22/50 13 March 2020

Runners and riders compete in the JCB Triumph Hurdle during day four of the Cheltenham Festival at Cheltenham Racecourse. Thousands of people attended where Gold Cup day amid great uncertainty as sports events up and down the United Kingdom are postponed and cancelled due to the Coronavirus outbreak

PA Images via Reuters Connect

23/50 12 March 2020

A worker makes her way along rows of daffodils, removing any rogue varieties, at Taylors Bulbs in Holbeach, Lincolnshire. The fourth generation family company plant over 35 million bulbs every year, and have held The Royal Warrant as Bulb Growers to Her Majesty The Queen since 1985

PA

24/50 11 March 2020

Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak poses for pictures with the Budget Box outside 11 Downing Street ahead of Britain’s first post-Brexit budget

AFP/Getty

25/50 10 March 2020

A Tate Modern gallery assistant interacts with the ‘Silver Clouds’ installation, at a press view of major new Andy Warhol exhibition at Tate Modern, which features classic pop art pieces and works never shown before in the UK

PA

26/50 9 March 2020

The Sub Dean and Canon Paster of Southwark, Canon Michael Rawson, left, blesses the statue of Santa Barbara and workers on one of the sites of the Thames Tideway Tunnel in London. Santa Barbara is the patron saint of tunnellers and by tradition a statue and shrine to her is placed at tunnel portals and the entrance to long tunnel headings to keep workers safe while underground. The 16 mile-long Thames Tideway Tunnel will prevent tens of millions of tonnes of sewage and rainwater run-off entering the river every year

PA

27/50 8 March 2020

An Afghan Hound dog is prepared for show at the Birmingham National Exhibition Centre (NEC) during the final day of the Crufts Dog Show

PA

28/50 7 March 2020

People taking part in the Million Women Rise march through central London, to demand an end to male violence against women and girls in all its forms

PA

29/50 6 March 2020

Crew members take a selfie beside the cab of The Flying Scotswoman, the LNER Edinburgh to London rail service which has an all-female crew to celebrate International Women’s Day, before it departs Edinburgh Waverley station

PA

30/50 5 March 2020

A poodle arrives for the first day of Crufts 2020 in Birmingham

Jason Skarratt/Flick.digital

31/50 4 March 2020

An Emergency Department Nurse during a demonstration of the Coronavirus pod and Covid-19 virus testing procedures set-up beside the Emergency Department of Antrim Area Hospital in Northern Ireland

PA

32/50 3 March 2020

A pedestrian wears a protective facemask while taking a bus in Westminster, London, on the day that Health Secretary Matt Hancock said that the number of people diagnosed with coronavirus in the UK has risen to 51

PA

33/50 2 March 2020

An artist at Madame Tussauds in London fits the museum’s waxwork of Prime Minister Boris Johnson with a baby carrier, following the recent announcement that he is expecting a baby with partner Carrie Symonds

PA

34/50 1 March 2020

A man dressed as Dewi Sant leads the St David’s day parade in Cardiff, where hundreds of people march through the city in celebration of the patron saint of Wales. Dewi Sant (Saint David in English) was the Welsh bishop of Mynyw (now St Davids) during the 6th century

PA

35/50 29 February 2020

A home flooded after the River Aire burst its banks in East Cowick, East Yorkshire

Getty

36/50 28 February 2020

Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg takes part in a “Youth Strike 4 Climate” protest march in Bristol, south west England. “Activism works, so I ask you to act,” she said

AFP/Getty

37/50 27 February 2020

Campaigners cheer outside the Royal Courts of Justice in London after they won a Court of Appeal challenge against controversial plans for a third runway at Heathrow

PA

38/50 26 February 2020

Temporary barriers have been overwhelmed by flood water in Bewdley, Shropshire

Getty

39/50 25 February 2020

Players take part in the Atherstone Ball Game in Warwickshire. The game honours a match played between Leicestershire and Warwickshire in 1199, when teams used a bag of gold as a ball, and which was won by Warwickshire

PA

40/50 24 February 2020

A couple shelter from waves crashing over the promenade in Folkestone, Kent, as bad weather continues to cause problems across the country

PA

41/50 23 February 2020

Viking re-enactors during the Jorvik Viking Festival in York, recognised as the largest event of its kind in Europe

PA

42/50 22 February 2020

Former Greek Finance minister Yanis Varoufakis, fashion designer Vivienne Westwood and editor in chief of WikiLeaks Kristinn Hrafnsonn attend a protest against the extradition of Julian Assange outside the Australian High Commission in London

Reuters

43/50 21 February 2020

A worker recovers stranded vehicles from flood water on the A761 in Paisley, Scotland

Getty

44/50 20 February 2020

Police officers outside Regents Park mosque in central London after a man was reportedly been stabbed in the neck. Footage from the scene showed a young white man in a red hooded top being led from the mosque by police

Reuters

45/50 19 February 2020

Floodwaters surround Upton upon Seven following Storm Dennis

Getty Images

46/50 18 February 2020

Models on the catwalk during the Bobby Abley show at London Fashion Week

PA

47/50 17 February 2020

Rachel Cox inspecting flood damage in her kitchen in Nantgarw, south Wales, where residents are returning to their homes to survey and repair the damage in the aftermath of Storm Dennis

PA

48/50 16 February 2020

Teme Street in Tenbury Wells is seen under floodwater from the overflowing River Teme, after Storm Dennis caused flooding across large swathes of Britain

AFP via Getty

49/50 15 February 2020

Models present creations at the Richard Quinn catwalk show during London Fashion Week in London

Reuters

50/50 14 February 2020

Climate change protesters march through Whitehall, London

PA

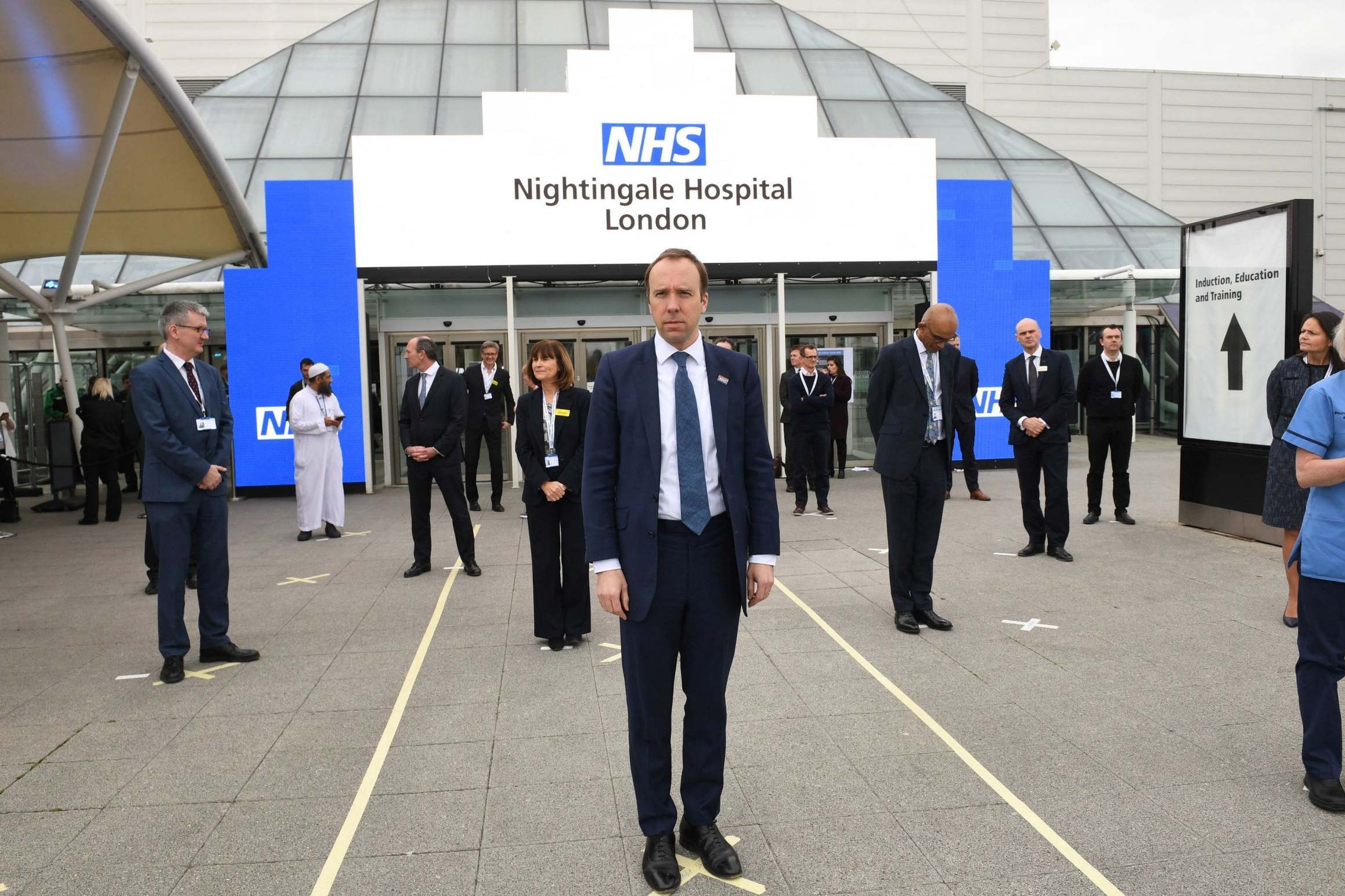

1/50 3 April 2020

Health Secretary Matt Hancock and NHS staff stand on marks on the ground, put in place to ensure social distancing guidelines are adhered to, at the opening of the NHS Nightingale Hospital at the ExCel centre in London, a temporary hospital with 4000 beds which has been set up for the treatment of Covid-19 patients. PA Photo. Picture date: Friday April 3, 2020. Split into more than 80 wards containing 42 beds each, the facility will be used to treat Covid-19 patients who have been transferred from other intensive care units across London.

PA

2/50 2 April 2020

A child at Westlands Primary School paints a poster in support of the NHS in Newcastle-under-Lyme

Reuters

3/50 1 April 2020

Staff wearing PPE of gloves and face masks, as a preactionary measure against Covid-19, disinfect an ambulance after it arrived with a patient at St Thomas’ Hospital in north London

AFP via Getty

4/50 31 March 2020

Llandudno Pier remains closed and deserted of tourists during the pandemic lockdown in Wales

Getty

5/50 30 March 2020

Waves break against the pier at Tynemouth, on the North East coast

PA

6/50 29 March 2020

Waves crash over a car on the seafront during windy conditions in Broadstairs, Kent

PA

7/50 28 March 2020

Derbyshire Police dye the “blue lagoon” in Harpur Hill, Buxton black, as gatherings there are “dangerous” and are “in contravention of the current instruction of the UK Government”

PA

8/50 27 March 2020

A road sign advising drivers to ‘stay home protect NHS saves lives’ is visible on the M80 near Banknock as the UK continues in lockdown to help curb the spread of the coronavirus

PA

9/50 26 March 2020

A postman wears a mask and gloves to deliver letters in Broadstairs, Kent, after Prime Minister Boris Johnson has put the UK in lockdown to help curb the spread of the coronavirus. PA Photo. Picture date: Thursday March 26, 2020. The UK’s coronavirus death toll reached 463 on Wednesday.

PA

10/50 25 March 2020

Members of the public out exercising on Brighton beach at sunset

Getty

11/50 24 March 2020

Military vehicles cross Westminster Bridge after members of the 101 Logistic Brigade delivered a consignment of medical masks to St Thomas’ hospital

Getty

12/50 23 March 2020

Commuters travel on the London underground during the Coronavirus pandemic

Getty

13/50 22 March 2020

People walk on the seafront after recent incidents of members of the public ignoring government advice on social distancing on in Hove

Getty

14/50 21 March 2020

A general view of an empty Trafalgar Square in London. There have as of now been 3,983 diagnosed coronavirus cases in the UK and 177 deaths

Getty

15/50 20 March 2020

Swans swim on the banks of the River Severn in Worcester

PA

16/50 19 March 2020

A piece of art by the artist, known as the Rebel Bear has appeared on a wall on Bank Street in Glasgow. The new addition to Glasgow’s street art is capturing the global Coronavirus crisis. The piece features a woman and a man pulling back to give each other a kiss

PA

17/50 18 March 2020

Students tend to Spring Lambs at Moreton Morrell College in Warwickshire

PA

18/50 17 March 2020

Caerphilly Castle in South Wales joins Tourism Ireland’s Global Greenings campaign to mark St Patrick’s Day

PA

19/50 16 March 2020

Shoppers form long queues ahead of the opening of a Costco wholesale store in Chingford

Getty

20/50 15 March 2020

Players sing songs in the changing room after their game of football at Hackney Marshes in London

Reuters

21/50 14 March 2020

Empty shelves in the laundry aisle of an Asda store in London

PA

22/50 13 March 2020

Runners and riders compete in the JCB Triumph Hurdle during day four of the Cheltenham Festival at Cheltenham Racecourse. Thousands of people attended where Gold Cup day amid great uncertainty as sports events up and down the United Kingdom are postponed and cancelled due to the Coronavirus outbreak

PA Images via Reuters Connect

23/50 12 March 2020

A worker makes her way along rows of daffodils, removing any rogue varieties, at Taylors Bulbs in Holbeach, Lincolnshire. The fourth generation family company plant over 35 million bulbs every year, and have held The Royal Warrant as Bulb Growers to Her Majesty The Queen since 1985

PA

24/50 11 March 2020

Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak poses for pictures with the Budget Box outside 11 Downing Street ahead of Britain’s first post-Brexit budget

AFP/Getty

25/50 10 March 2020

A Tate Modern gallery assistant interacts with the ‘Silver Clouds’ installation, at a press view of major new Andy Warhol exhibition at Tate Modern, which features classic pop art pieces and works never shown before in the UK

PA

26/50 9 March 2020

The Sub Dean and Canon Paster of Southwark, Canon Michael Rawson, left, blesses the statue of Santa Barbara and workers on one of the sites of the Thames Tideway Tunnel in London. Santa Barbara is the patron saint of tunnellers and by tradition a statue and shrine to her is placed at tunnel portals and the entrance to long tunnel headings to keep workers safe while underground. The 16 mile-long Thames Tideway Tunnel will prevent tens of millions of tonnes of sewage and rainwater run-off entering the river every year

PA

27/50 8 March 2020

An Afghan Hound dog is prepared for show at the Birmingham National Exhibition Centre (NEC) during the final day of the Crufts Dog Show

PA

28/50 7 March 2020

People taking part in the Million Women Rise march through central London, to demand an end to male violence against women and girls in all its forms

PA

29/50 6 March 2020

Crew members take a selfie beside the cab of The Flying Scotswoman, the LNER Edinburgh to London rail service which has an all-female crew to celebrate International Women’s Day, before it departs Edinburgh Waverley station

PA

30/50 5 March 2020

A poodle arrives for the first day of Crufts 2020 in Birmingham

Jason Skarratt/Flick.digital

31/50 4 March 2020

An Emergency Department Nurse during a demonstration of the Coronavirus pod and Covid-19 virus testing procedures set-up beside the Emergency Department of Antrim Area Hospital in Northern Ireland

PA

32/50 3 March 2020

A pedestrian wears a protective facemask while taking a bus in Westminster, London, on the day that Health Secretary Matt Hancock said that the number of people diagnosed with coronavirus in the UK has risen to 51

PA

33/50 2 March 2020

An artist at Madame Tussauds in London fits the museum’s waxwork of Prime Minister Boris Johnson with a baby carrier, following the recent announcement that he is expecting a baby with partner Carrie Symonds

PA

34/50 1 March 2020

A man dressed as Dewi Sant leads the St David’s day parade in Cardiff, where hundreds of people march through the city in celebration of the patron saint of Wales. Dewi Sant (Saint David in English) was the Welsh bishop of Mynyw (now St Davids) during the 6th century

PA

35/50 29 February 2020

A home flooded after the River Aire burst its banks in East Cowick, East Yorkshire

Getty

36/50 28 February 2020

Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg takes part in a “Youth Strike 4 Climate” protest march in Bristol, south west England. “Activism works, so I ask you to act,” she said

AFP/Getty

37/50 27 February 2020

Campaigners cheer outside the Royal Courts of Justice in London after they won a Court of Appeal challenge against controversial plans for a third runway at Heathrow

PA

38/50 26 February 2020

Temporary barriers have been overwhelmed by flood water in Bewdley, Shropshire

Getty

39/50 25 February 2020

Players take part in the Atherstone Ball Game in Warwickshire. The game honours a match played between Leicestershire and Warwickshire in 1199, when teams used a bag of gold as a ball, and which was won by Warwickshire

PA

40/50 24 February 2020

A couple shelter from waves crashing over the promenade in Folkestone, Kent, as bad weather continues to cause problems across the country

PA

41/50 23 February 2020

Viking re-enactors during the Jorvik Viking Festival in York, recognised as the largest event of its kind in Europe

PA

42/50 22 February 2020

Former Greek Finance minister Yanis Varoufakis, fashion designer Vivienne Westwood and editor in chief of WikiLeaks Kristinn Hrafnsonn attend a protest against the extradition of Julian Assange outside the Australian High Commission in London

Reuters

43/50 21 February 2020

A worker recovers stranded vehicles from flood water on the A761 in Paisley, Scotland

Getty

44/50 20 February 2020

Police officers outside Regents Park mosque in central London after a man was reportedly been stabbed in the neck. Footage from the scene showed a young white man in a red hooded top being led from the mosque by police

Reuters

45/50 19 February 2020

Floodwaters surround Upton upon Seven following Storm Dennis

Getty Images

46/50 18 February 2020

Models on the catwalk during the Bobby Abley show at London Fashion Week

PA

47/50 17 February 2020

Rachel Cox inspecting flood damage in her kitchen in Nantgarw, south Wales, where residents are returning to their homes to survey and repair the damage in the aftermath of Storm Dennis

PA

48/50 16 February 2020

Teme Street in Tenbury Wells is seen under floodwater from the overflowing River Teme, after Storm Dennis caused flooding across large swathes of Britain

AFP via Getty

49/50 15 February 2020

Models present creations at the Richard Quinn catwalk show during London Fashion Week in London

Reuters

50/50 14 February 2020

Climate change protesters march through Whitehall, London

PA

Her manifesto for power taps into her roots as a union organiser, focusing on transforming Labour into a fighting machine capable of taking on Boris Johnson’s emboldened Conservatives in 2024.

She has described herself as more “bombastic” than Corbyn, saying she would demand more discipline from the party than he did.

Instead she has likened herself to the pugnacious John Prescott, a fitting comparison for the battle ahead.